8 April 2016 to 10 June 2015

¶ More Noises at Once · 8 April 2016 listen/tech

For convoluted logistical reasons, the maps on Every Noise at Once haven't been updated in a while. The associated The Sound Of playlists have kept updating every week, but the genre list itself, the artist/genre assignments, and some of the other bits of map infrastructure have been involved in a slow belated technical migration as a result of the acquisition of the Echo Nest by Spotify two years ago.

But this is all done now, or close enough, and the map is updated and updating again!

Presumably nobody was really waiting impatiently to find out how many pixels left or right aggrotech should have shifted during this time. Encouragingly, ripping out all the data for the map and replacing it with new data didn't radically change everything. By which I mean, of course, that it initially wrought abject chaos, but after a day or two of frowning at code I wrote a long time ago I got the entropy basically re-contained. Mostly the products of this migration are straightforwardly good, and just magically make everything better. But sometimes the magic fails, and it takes a little human attention to allow the betterness to assert itself properly, so if you notice anything strange, let me know.

More notably, reactivating the whole system makes it possible to add and remove genres again. A few marginal genres basically got absorbed by the data-fueled expansion of more prominent or interesting things, but mostly the deeper data made it possible to model known things I hadn't been able to include before, and to give names to obscure and/or emerging clusters that our old instruments weren't powerful enough to clearly discern. The net effect takes us to 1435 genres as of today, and these are the new ones:

african gospel

alt-indie rock

anthem emo

anthem worship

bass trap

beats

chamber choir

chamber psych

channel pop

christian relaxative

cornetas y tambores

czech hip hop

danspunk

deep australian indie

deep big room

deep cumbia sonidera

deep danish pop

deep german pop rock

deep groove house

deep indie r&b

deep latin hip hop

deep melodic euro house

deep new americana

deep pop edm

deep pop r&b

deep southern trap

deep swedish indie pop

deep taiwanese pop

deep underground hip hop

drill

electro bailando

finnish dance pop

fluxwork

francoton

french indietronica

german street punk

groove room

hungarian hip hop

indie anthem-folk

indiecoustica

indie garage rock

indie poptimism

indie psych-rock

indie rockism

kids dance party

kwaito house

lift kit

norwegian indie

otacore

pixie

pop flamenco

pop reggaeton

post-screamo

preverb

redneck

romantico

russelater

slow game

spanish noise pop

spanish rock

strut

swedish eurodance

swedish idol pop

teen pop

tracestep

vapor pop

vapor soul

vapor twitch

voidgaze

west coast trap

Some of these, to be clear, although not necessarily the ones you think, I made up. That is, they are names I made up for music and listening modes that I did not make up. Whether this makes them "really" genres is an existential question we can debate while we listen.

But this is all done now, or close enough, and the map is updated and updating again!

Presumably nobody was really waiting impatiently to find out how many pixels left or right aggrotech should have shifted during this time. Encouragingly, ripping out all the data for the map and replacing it with new data didn't radically change everything. By which I mean, of course, that it initially wrought abject chaos, but after a day or two of frowning at code I wrote a long time ago I got the entropy basically re-contained. Mostly the products of this migration are straightforwardly good, and just magically make everything better. But sometimes the magic fails, and it takes a little human attention to allow the betterness to assert itself properly, so if you notice anything strange, let me know.

More notably, reactivating the whole system makes it possible to add and remove genres again. A few marginal genres basically got absorbed by the data-fueled expansion of more prominent or interesting things, but mostly the deeper data made it possible to model known things I hadn't been able to include before, and to give names to obscure and/or emerging clusters that our old instruments weren't powerful enough to clearly discern. The net effect takes us to 1435 genres as of today, and these are the new ones:

african gospel

alt-indie rock

anthem emo

anthem worship

bass trap

beats

chamber choir

chamber psych

channel pop

christian relaxative

cornetas y tambores

czech hip hop

danspunk

deep australian indie

deep big room

deep cumbia sonidera

deep danish pop

deep german pop rock

deep groove house

deep indie r&b

deep latin hip hop

deep melodic euro house

deep new americana

deep pop edm

deep pop r&b

deep southern trap

deep swedish indie pop

deep taiwanese pop

deep underground hip hop

drill

electro bailando

finnish dance pop

fluxwork

francoton

french indietronica

german street punk

groove room

hungarian hip hop

indie anthem-folk

indiecoustica

indie garage rock

indie poptimism

indie psych-rock

indie rockism

kids dance party

kwaito house

lift kit

norwegian indie

otacore

pixie

pop flamenco

pop reggaeton

post-screamo

preverb

redneck

romantico

russelater

slow game

spanish noise pop

spanish rock

strut

swedish eurodance

swedish idol pop

teen pop

tracestep

vapor pop

vapor soul

vapor twitch

voidgaze

west coast trap

Some of these, to be clear, although not necessarily the ones you think, I made up. That is, they are names I made up for music and listening modes that I did not make up. Whether this makes them "really" genres is an existential question we can debate while we listen.

For a long time, I wrote a verbose, discursive weekly music-review column called The War Against Silence. For most of a decade, my listening life, if not my whole life, was organized around this, and thus procedurally dedicated to filtering through as much new music as I could physically buy and play in order to find a record or two each week to which I could attach some kind of story about what it's like to believe that music is the thing that humans do best.

In my farewell column I said, among other things, that "Organizing my reactions to new music is no longer the central motif of my narrative of identity."

I trust that I meant that when I wrote it, so apparently there was at least a moment in my life when it was true. Or, rather, it's still true, but there must have been a moment in my life when it seemed significant. I got married around then, and our daughter is now 8. So of course there's now more to it. I'm pretty sure my "narrative of identity", if I still have such a pompous-sounding thing, is not organized enough to have a central motif.

But I've only gradually realized how much this is more than just entropy. My attention is, if anything, exponentially more focused on music discovery than ever before. This process used to be logistically constrained by the low bandwidth of pre-internet research and pre-streaming shopping, and the slow pace of album-sized listening, and the constant arbitrary discipline of annotating individual albums with over-explicated life-checkpoints. Now there's Spotify. And since I work there, too, I not only have the Spotify you see, but also a hundred strange extensions and elaborations and experiments that haven't evolved into public features yet. We all have an ocean of sort-of all the world's music to swim in, now, but I also have erratic prototypes of god-robots that can, sometimes, make the currents reflow to bring every yearning message-bottle straight to my private personal beach.

And partly as a result, but also partly as cause, over the last few years I've more or less inverted my musical attachment-model. I do still listen to whole albums sometimes, and sometimes fall in love intensely with individual artists. But I used to draw the boundary of "my" musical life there, and "exploration" was a pre-listening thing I did on the other side of that line. Only the music I wrote about was really mine; I accepted no responsibility for the rest of it.

That now seems to me like useless, inexplicable, atavistic and basically intolerable isolationism. I accept responsibility for nothing and everything. There's no line. Exploration is listening, not a way of preparing for listening. I can now spend a happy afternoon immersed in auto-collated Norwegian Hip Hop, and at the end I can't necessarily tell you a single name. But I'm not trying to become a Norwegian Hip Hop specialist, I'm trying to listen. It's all listening. More listening is better. More variety is better. More languages, more instruments, more surprise. More everything. I spend whole days awash in noises I haven't even made up names for yet. Stopping to write a 3000-word essay about every single record seems literally counter-productive and emotionally excruciating, a sacrifice of so much other possible listening that you might as well be summoning death.

And yet, I still believe that thing about the unexamined life, and hearing without taking some kind of note isn't quite listening. You can't make tools for music discovery without thinking about the process. Without self-awareness and referentiality, you don't have discovery, you have wandering.

New music still has a market periodicity, too, and my life has obvious weekly cycles, so I've found myself over the last year making weekly playlists of some of the things I come across. And instead of elaborate essays in which the music is used as an excuse for introspection, I've been annotating each track with the shortest possible explanation I can come up with for what I thought it was when I thought it was worth remembering.

I originally started posting these annotated lists on a discussion board, just as part of an ongoing conversation. But as the conversation underwent its natural dissipation, I keep making the lists, and they settled into a format. And I finally got around to making an actual home for them, because I found myself wanting a better way to keep track. So although I've been making them for almost exactly a year, this is also kind of the beginning.

Here, then, I introduce to you:

New Particles

It's a weekly annotated-playlist series. Some weeks there's a lot of music, some weeks there's less. In theory some weeks there could be nothing, but that doesn't seem to happen in practice. The annotations are brief and not guaranteed to make sense. The music is not likely to seem coherent to anybody but me, and the odds seem good that, no matter what your tastes, I will regularly include some kind of thing you can't stand.

Why you should care what music seems interesting to me, or why, I don't exactly know. Some people cared about my old column, but this is kind of the formal opposite of that. Maybe this is only for me.

But I tried to not do it, and failed. So now it exists.

Welcome!

In my farewell column I said, among other things, that "Organizing my reactions to new music is no longer the central motif of my narrative of identity."

I trust that I meant that when I wrote it, so apparently there was at least a moment in my life when it was true. Or, rather, it's still true, but there must have been a moment in my life when it seemed significant. I got married around then, and our daughter is now 8. So of course there's now more to it. I'm pretty sure my "narrative of identity", if I still have such a pompous-sounding thing, is not organized enough to have a central motif.

But I've only gradually realized how much this is more than just entropy. My attention is, if anything, exponentially more focused on music discovery than ever before. This process used to be logistically constrained by the low bandwidth of pre-internet research and pre-streaming shopping, and the slow pace of album-sized listening, and the constant arbitrary discipline of annotating individual albums with over-explicated life-checkpoints. Now there's Spotify. And since I work there, too, I not only have the Spotify you see, but also a hundred strange extensions and elaborations and experiments that haven't evolved into public features yet. We all have an ocean of sort-of all the world's music to swim in, now, but I also have erratic prototypes of god-robots that can, sometimes, make the currents reflow to bring every yearning message-bottle straight to my private personal beach.

And partly as a result, but also partly as cause, over the last few years I've more or less inverted my musical attachment-model. I do still listen to whole albums sometimes, and sometimes fall in love intensely with individual artists. But I used to draw the boundary of "my" musical life there, and "exploration" was a pre-listening thing I did on the other side of that line. Only the music I wrote about was really mine; I accepted no responsibility for the rest of it.

That now seems to me like useless, inexplicable, atavistic and basically intolerable isolationism. I accept responsibility for nothing and everything. There's no line. Exploration is listening, not a way of preparing for listening. I can now spend a happy afternoon immersed in auto-collated Norwegian Hip Hop, and at the end I can't necessarily tell you a single name. But I'm not trying to become a Norwegian Hip Hop specialist, I'm trying to listen. It's all listening. More listening is better. More variety is better. More languages, more instruments, more surprise. More everything. I spend whole days awash in noises I haven't even made up names for yet. Stopping to write a 3000-word essay about every single record seems literally counter-productive and emotionally excruciating, a sacrifice of so much other possible listening that you might as well be summoning death.

And yet, I still believe that thing about the unexamined life, and hearing without taking some kind of note isn't quite listening. You can't make tools for music discovery without thinking about the process. Without self-awareness and referentiality, you don't have discovery, you have wandering.

New music still has a market periodicity, too, and my life has obvious weekly cycles, so I've found myself over the last year making weekly playlists of some of the things I come across. And instead of elaborate essays in which the music is used as an excuse for introspection, I've been annotating each track with the shortest possible explanation I can come up with for what I thought it was when I thought it was worth remembering.

I originally started posting these annotated lists on a discussion board, just as part of an ongoing conversation. But as the conversation underwent its natural dissipation, I keep making the lists, and they settled into a format. And I finally got around to making an actual home for them, because I found myself wanting a better way to keep track. So although I've been making them for almost exactly a year, this is also kind of the beginning.

Here, then, I introduce to you:

New Particles

It's a weekly annotated-playlist series. Some weeks there's a lot of music, some weeks there's less. In theory some weeks there could be nothing, but that doesn't seem to happen in practice. The annotations are brief and not guaranteed to make sense. The music is not likely to seem coherent to anybody but me, and the odds seem good that, no matter what your tastes, I will regularly include some kind of thing you can't stand.

Why you should care what music seems interesting to me, or why, I don't exactly know. Some people cared about my old column, but this is kind of the formal opposite of that. Maybe this is only for me.

But I tried to not do it, and failed. So now it exists.

Welcome!

¶ Pazz & Jop and Music 2015 · 12 January 2016 listen/tech

The 2015 edition of the Village Voice's annual Pazz & Jop music-critics poll is out.

As has been the case for a few years now, since they got tired of me complaining about tabulation errors after they published it, I have been in charge of tabulating it. There is an obvious moral about complaining there. In the process of doing this I generate a lot of additional statistics, because that's a thing I basically can't stop myself from doing even when I'm asleep. There's a Tabulation Notes write-up I did that explains some of it.

I also vote in the poll. I go back and forth on strategies for this, as I have way more than 10 albums and 10 songs I like in any given year. This year I did a metal-only album ballot and a synthpop-only singles ballot, because those felt like the things I knew the most deeply from the year. Not that this "depth" is actually apparent or significant to anybody but me, but it got me out of voting paralysis.

Here's my ballot on the Voice's site and on my stats site.

If you want to listen to a bunch of music that I liked last year, I have also expanded both these 10-entry lists into 100-song playlists, one for metal and one for "non-metal" (also sometimes just called "music").

As has been the case for a few years now, since they got tired of me complaining about tabulation errors after they published it, I have been in charge of tabulating it. There is an obvious moral about complaining there. In the process of doing this I generate a lot of additional statistics, because that's a thing I basically can't stop myself from doing even when I'm asleep. There's a Tabulation Notes write-up I did that explains some of it.

I also vote in the poll. I go back and forth on strategies for this, as I have way more than 10 albums and 10 songs I like in any given year. This year I did a metal-only album ballot and a synthpop-only singles ballot, because those felt like the things I knew the most deeply from the year. Not that this "depth" is actually apparent or significant to anybody but me, but it got me out of voting paralysis.

Here's my ballot on the Voice's site and on my stats site.

If you want to listen to a bunch of music that I liked last year, I have also expanded both these 10-entry lists into 100-song playlists, one for metal and one for "non-metal" (also sometimes just called "music").

¶ Our economy relies on math. Too bad our culture doesn't value it. · 20 December 2015 listen/tech

A couple days ago The Washington Post published a plaintive T Bone Burnett lament headlined "Our culture loves music. Too bad our economy doesn’t value it."

The specific outrage that the piece builds from is this quote:

"In 2014, sales from vinyl records made more than all of the ad-supported on-demand streams on services such as YouTube."

which comes from this article at The Verge:

Vinyl sales are more valuable than ad-supported streaming in 2015

which is referring to this RIAA report:

News and Notes on 2015 Mid-Year RIAA Shipment and Revenue Statistics

But if you you read the actual report, you discover that this comparison is wildly and almost certainly deliberately misleading.

In the case of ad-supported on-demand streaming (a category which, for technical reasons, really only counts YouTube and a small part of Spotify), the report is calculating actual royalties paid to the music industry, which is sensible.

In the case of vinyl, however, the report is calculating the hypothetical total suggested retail prices of all vinyl albums shipped.

So:

- shipped, not sold

- suggested retail prices, not actual prices paid

- suggested gross prices paid to retailers, not net revenue to the music industry after taking into account wholesale prices and manufacturing and distribution costs

This comparison is insane. It's like saying that your dog is taller than you based on how tall the dog would be if it learned to walk upright on the amazing stilts you dreamed about making.

Tellingly, the RIAA does not provide any of the figures necessary to accurately correct the comparison, but my rough guess is that the vinyl figure is inflated by a factor of somewhere between 4 and 10.

A more plausible conclusion, thus, would be something like "Even amidst a crazed temporary vinyl-fetish bubble-market, 'free' ad-supported YouTube and Spotify streams actually made more money for musicians by a wide margin."

And of course this arbitrary legal streaming category excludes Pandora and other non-on-demand streaming, which added more than twice as much revenue to the music industry, and all paid-subscrition streaming like Spotify Premium, which added three times as much.

Even more glaringly, the equation also excludes paid downloading, and CDs and other physical formats. But put together, all stream/download-based music sources contributed 4 times as much actual music-industry revenue as the hypothetical total retail value of all the physically-distributed music. So by my 4-10x guess at figure inflation, this would mean that these newfangled demons from the callous musician-hating technology cabal produced somewhere between 16x and 40x as much music-industry support as the old, supposedly-musician-loving physical objects.

So while I'm not claiming that there aren't still serious systemic problems in the music economy, we're never going to fix them by letting disingenuous numbers lead us on literally counter-productive crusades against the future.

(Minor PS to Burnett: It also makes particularly bad sense to portray Taylor Swift as a defender of musicians in this specific context. When she dramatically took her music off of Spotify, which has both free and paid tiers, she left it on YouTube, which at the time had only a free tier and later changed to exactly the same free/paid model as Spotify. This might be a defensible business decision for her or her corporate backers, but there's no coherent way in which it's a moral one that has anything to do with other people.)

(PPS for anybody reading this who doesn't already know me: I work at Spotify, but this is my personal blog and these are my personal opinions. I am not directly involved in Spotify business deals or music-industry policy, but I have loved music for far, far longer than I have worked at Spotify, and I wouldn't be doing the latter if I thought it was hostile to the former.)

The specific outrage that the piece builds from is this quote:

"In 2014, sales from vinyl records made more than all of the ad-supported on-demand streams on services such as YouTube."

which comes from this article at The Verge:

Vinyl sales are more valuable than ad-supported streaming in 2015

which is referring to this RIAA report:

News and Notes on 2015 Mid-Year RIAA Shipment and Revenue Statistics

But if you you read the actual report, you discover that this comparison is wildly and almost certainly deliberately misleading.

In the case of ad-supported on-demand streaming (a category which, for technical reasons, really only counts YouTube and a small part of Spotify), the report is calculating actual royalties paid to the music industry, which is sensible.

In the case of vinyl, however, the report is calculating the hypothetical total suggested retail prices of all vinyl albums shipped.

So:

- shipped, not sold

- suggested retail prices, not actual prices paid

- suggested gross prices paid to retailers, not net revenue to the music industry after taking into account wholesale prices and manufacturing and distribution costs

This comparison is insane. It's like saying that your dog is taller than you based on how tall the dog would be if it learned to walk upright on the amazing stilts you dreamed about making.

Tellingly, the RIAA does not provide any of the figures necessary to accurately correct the comparison, but my rough guess is that the vinyl figure is inflated by a factor of somewhere between 4 and 10.

A more plausible conclusion, thus, would be something like "Even amidst a crazed temporary vinyl-fetish bubble-market, 'free' ad-supported YouTube and Spotify streams actually made more money for musicians by a wide margin."

And of course this arbitrary legal streaming category excludes Pandora and other non-on-demand streaming, which added more than twice as much revenue to the music industry, and all paid-subscrition streaming like Spotify Premium, which added three times as much.

Even more glaringly, the equation also excludes paid downloading, and CDs and other physical formats. But put together, all stream/download-based music sources contributed 4 times as much actual music-industry revenue as the hypothetical total retail value of all the physically-distributed music. So by my 4-10x guess at figure inflation, this would mean that these newfangled demons from the callous musician-hating technology cabal produced somewhere between 16x and 40x as much music-industry support as the old, supposedly-musician-loving physical objects.

So while I'm not claiming that there aren't still serious systemic problems in the music economy, we're never going to fix them by letting disingenuous numbers lead us on literally counter-productive crusades against the future.

(Minor PS to Burnett: It also makes particularly bad sense to portray Taylor Swift as a defender of musicians in this specific context. When she dramatically took her music off of Spotify, which has both free and paid tiers, she left it on YouTube, which at the time had only a free tier and later changed to exactly the same free/paid model as Spotify. This might be a defensible business decision for her or her corporate backers, but there's no coherent way in which it's a moral one that has anything to do with other people.)

(PPS for anybody reading this who doesn't already know me: I work at Spotify, but this is my personal blog and these are my personal opinions. I am not directly involved in Spotify business deals or music-industry policy, but I have loved music for far, far longer than I have worked at Spotify, and I wouldn't be doing the latter if I thought it was hostile to the former.)

¶ (periodic reminder) · 6 December 2015

YOUR IMAGINATION

IS MORE POWERFUL

THAN YOUR ENEMIES

IS MORE POWERFUL

THAN YOUR ENEMIES

¶ A Fancier Hat · 4 December 2015 listen/tech

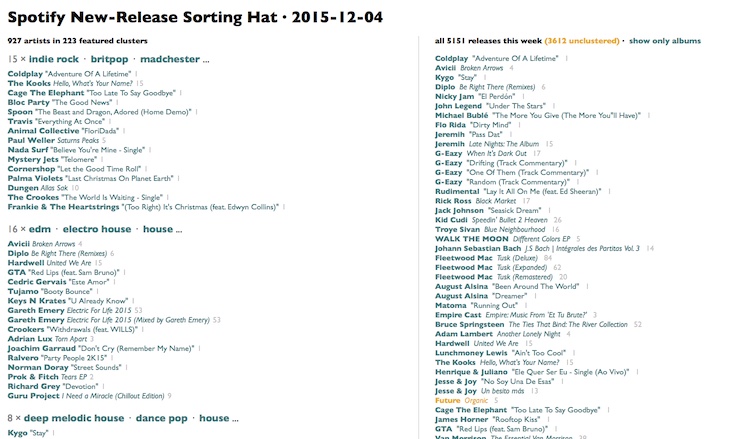

If you like new music but hate text, the Sorting Hat had a lot of both. I've changed it a little, in a way I should probably just explain with a quick before-and-after:

And if pictures aren't exciting enough by themselves, I've hooked up these particular pictures to play preview clips if you click them. Two senses down, three to go.

I didn't put images on the big list of thousands of releases on the right, because I did and my browser got very sad about it and I had to spend a lot of time apologizing. But you can click the little gray track-count numbers to hear previews on that side of the page, too.

And if you really, really don't like images, there's a tiny inscrutable gray widget in the top right corner of the page that you can click to put things mostly back how they were before, except a little nicer, and with the previews.

PS: In working on this I had another good reminder of the value of already knowing some right answers to the questions you ask. I made a new song of my own last weekend, and it comes "out" today, but when I generated this week's Sorting Hat initially, my song wasn't on the list.

The reason turned out to be a small, subtle bug that only affected releases by extremely obscure artists (I currently have six (6) monthly listeners), which made it unlikely that I would ever have noticed it if I hadn't been looking for my own song.

It's fixed now. See if you can figure out which one is mine. I'll give you a hint. It's this one:

Maybe you don't care, but I do, and so does everybody else with 6 listeners who dreams of one day having 12 or even 20.

PPS: And if you are interested in discovering interesting music that is not quite as obscure as mine, you might enjoy some of these:

And if pictures aren't exciting enough by themselves, I've hooked up these particular pictures to play preview clips if you click them. Two senses down, three to go.

I didn't put images on the big list of thousands of releases on the right, because I did and my browser got very sad about it and I had to spend a lot of time apologizing. But you can click the little gray track-count numbers to hear previews on that side of the page, too.

And if you really, really don't like images, there's a tiny inscrutable gray widget in the top right corner of the page that you can click to put things mostly back how they were before, except a little nicer, and with the previews.

PS: In working on this I had another good reminder of the value of already knowing some right answers to the questions you ask. I made a new song of my own last weekend, and it comes "out" today, but when I generated this week's Sorting Hat initially, my song wasn't on the list.

The reason turned out to be a small, subtle bug that only affected releases by extremely obscure artists (I currently have six (6) monthly listeners), which made it unlikely that I would ever have noticed it if I hadn't been looking for my own song.

It's fixed now. See if you can figure out which one is mine. I'll give you a hint. It's this one:

Maybe you don't care, but I do, and so does everybody else with 6 listeners who dreams of one day having 12 or even 20.

PPS: And if you are interested in discovering interesting music that is not quite as obscure as mine, you might enjoy some of these:

¶ Warm Worms Against Winter · 1 December 2015 listen/tech

It's dark and cold and grim, and then the Christmas music starts.

Whether that makes things better or worse for you is your own decision, but at Spotify we're trying to help you either way.

So we try to keep Christmas music mostly out of The Needle, which is harder than you might think, because weary Christmas standards being dragged out of the bins show an activity curve disconcertingly similar to that of emergent new hipnesses.

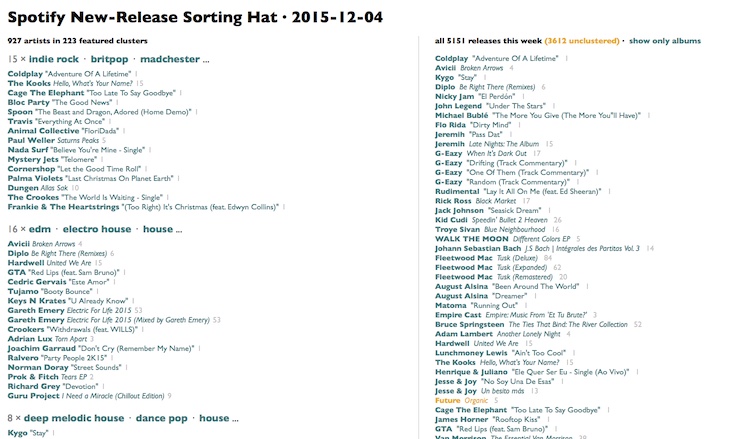

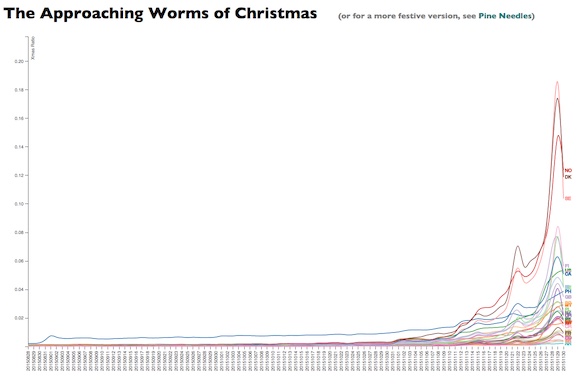

But this year, instead of just trying to suppress this surge, I decided to suppress it but also chart it. And thus we get this, The Approaching Worms of Christmas:

This chart will be updated every day or two until Christmas, and then maybe a few days afterwards just so we can all feel calmer again.

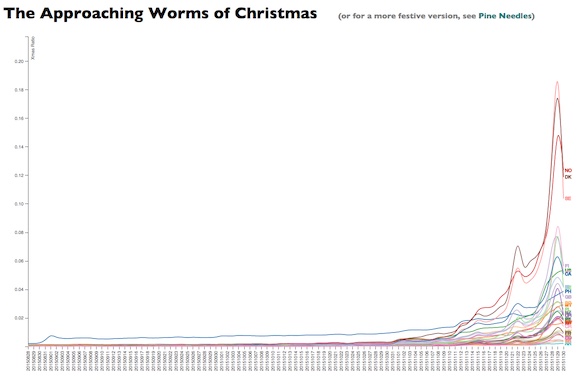

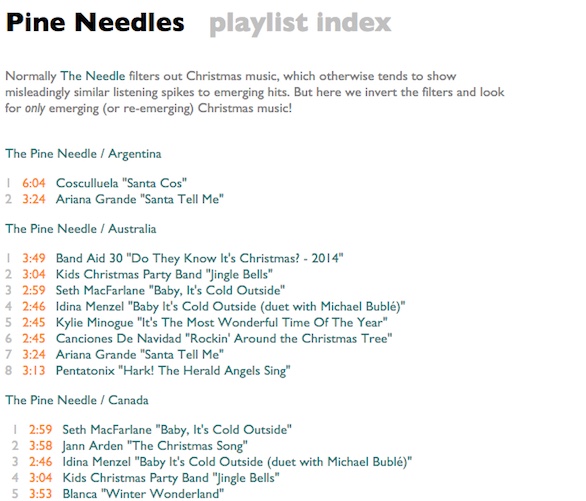

Watching the worms rise, actually, I also became morbidly curious what all that music was, and so I also also reversed the polarity of my anti-Christmas-music filters for The Needle, to try to only get rising (or re-surfacing) Christmas music. And of course the results of this could only be called Pine Needles:

These will also be updated dailyish until Christmas. I don't actually know whether they will end up reverting to chestnuts, or splaying into unimaginable craziness. We'll see. What's the fun of building a machine if you already know what it's going to do?

At any rate, welcome to the winter. Stay warm. There's music. It'll be OK.

Whether that makes things better or worse for you is your own decision, but at Spotify we're trying to help you either way.

So we try to keep Christmas music mostly out of The Needle, which is harder than you might think, because weary Christmas standards being dragged out of the bins show an activity curve disconcertingly similar to that of emergent new hipnesses.

But this year, instead of just trying to suppress this surge, I decided to suppress it but also chart it. And thus we get this, The Approaching Worms of Christmas:

This chart will be updated every day or two until Christmas, and then maybe a few days afterwards just so we can all feel calmer again.

Watching the worms rise, actually, I also became morbidly curious what all that music was, and so I also also reversed the polarity of my anti-Christmas-music filters for The Needle, to try to only get rising (or re-surfacing) Christmas music. And of course the results of this could only be called Pine Needles:

These will also be updated dailyish until Christmas. I don't actually know whether they will end up reverting to chestnuts, or splaying into unimaginable craziness. We'll see. What's the fun of building a machine if you already know what it's going to do?

At any rate, welcome to the winter. Stay warm. There's music. It'll be OK.

¶ Bombs Bursting in Stereo · 9 July 2015 listen/tech

During an interview with Wired, one of my Spotify co-workers explained the depth of our listening data by saying that we knew, for example, what the hottest song was in Cleveland on the 4th of July.

This was intended rhetorically, but the interviewer, reasonably if maybe over-literally, asked him what song it actually was. And thus I got an email.

We do, in fact, know what the hottest song was in Cleveland on the 4th of July. It was (for at least one definition of "hottest") Lee Greenwood's "God Bless The U.S.A.".

But I never like one-song answers when an army of semi-autonomous robots would suffice. Obviously we know a lot more than this one song. Patriotic July 4th listening spikes aren't as sharp or wide as the ones around Christmas, but that kind of just makes them easier to detect. And because July 4th is a native holiday here in the US, where Christmas is imported, the spikes are also interestingly regionalized.

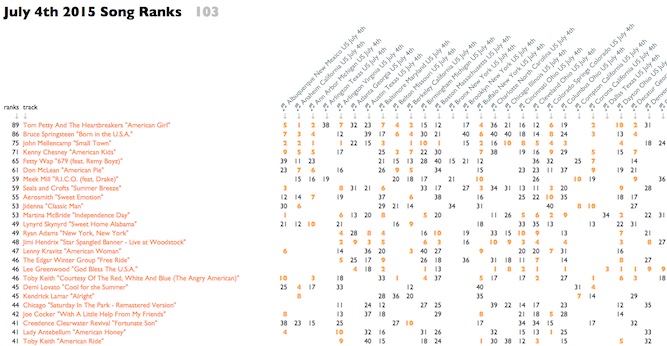

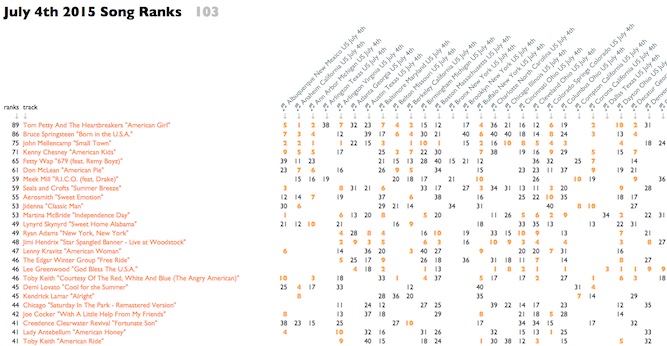

So I did a little analysis of the songs whose Spotify streaming spiked most dramatically in individual American cities on July 4 compared to the rest of the world in the preceding week. 103 cities had distinct enough patterns to make statistically relevant top-40 lists of these songs, so I made playlists for all of those (and a sampler with 1 song from each), and then combined them into this insane grid-thing I use for making abstruse sense of a lot of lists at once:

Each number in the grid is the rank of that row's song in that column's city's 4th of July list. From this we can see that Tom Petty and The Heartbreakers' "American Girl" is the 4th of July song shared by the most cities. (But it ranks quite differently in different places, and some of the places where it doesn't even make the top 40 form a potentially telling set: the Bronx, Compton, Detroit, Houston, Newark...)

Pick your own city (the names along the top are links to the individual playlists in Spotify) and see if it sounds familiar.

I started to try to take the non-4th songs out of this, but quickly decided that that made things less interesting, so I didn't. This is what we were listening to on the 4th of July, 2015. There weren't fireworks all day, and next year will be partly different just like it will be partly the same.

If you like moving parts, you can re-center the grid by clicking the little gray arrow under any city. The cities whose listening was most similar to Cleveland's are mostly cities similarly insulated from glamor: Plano, Louisville, Cincinnati, St. Louis, Indianapolis, Pittsburgh, Orlando. But then there's Boston, not far away after all, with 3 of the same songs as Cleveland in the top 10, and more than half their top 40s in common. This makes sense to me. Bright lights and loud noises appeal to fairly basic instincts, and we are certainly drawn to them here.

But then, if you spin it again and look at the country from Boston's point of view, there's Portland Oregon, and San Francisco, and Seattle and New York and DC. I don't think you'd mistake Boston for John Mellencamp's "Small Town" for longer than a day. We wave the flags with enthusiasm, but then the cannons fire, and the last rockets leave the barges in the Charles, and before very long it's dark and quiet and north-eastern again, and we turn and walk back through the streets to our homes.

This was intended rhetorically, but the interviewer, reasonably if maybe over-literally, asked him what song it actually was. And thus I got an email.

We do, in fact, know what the hottest song was in Cleveland on the 4th of July. It was (for at least one definition of "hottest") Lee Greenwood's "God Bless The U.S.A.".

But I never like one-song answers when an army of semi-autonomous robots would suffice. Obviously we know a lot more than this one song. Patriotic July 4th listening spikes aren't as sharp or wide as the ones around Christmas, but that kind of just makes them easier to detect. And because July 4th is a native holiday here in the US, where Christmas is imported, the spikes are also interestingly regionalized.

So I did a little analysis of the songs whose Spotify streaming spiked most dramatically in individual American cities on July 4 compared to the rest of the world in the preceding week. 103 cities had distinct enough patterns to make statistically relevant top-40 lists of these songs, so I made playlists for all of those (and a sampler with 1 song from each), and then combined them into this insane grid-thing I use for making abstruse sense of a lot of lists at once:

Each number in the grid is the rank of that row's song in that column's city's 4th of July list. From this we can see that Tom Petty and The Heartbreakers' "American Girl" is the 4th of July song shared by the most cities. (But it ranks quite differently in different places, and some of the places where it doesn't even make the top 40 form a potentially telling set: the Bronx, Compton, Detroit, Houston, Newark...)

Pick your own city (the names along the top are links to the individual playlists in Spotify) and see if it sounds familiar.

I started to try to take the non-4th songs out of this, but quickly decided that that made things less interesting, so I didn't. This is what we were listening to on the 4th of July, 2015. There weren't fireworks all day, and next year will be partly different just like it will be partly the same.

If you like moving parts, you can re-center the grid by clicking the little gray arrow under any city. The cities whose listening was most similar to Cleveland's are mostly cities similarly insulated from glamor: Plano, Louisville, Cincinnati, St. Louis, Indianapolis, Pittsburgh, Orlando. But then there's Boston, not far away after all, with 3 of the same songs as Cleveland in the top 10, and more than half their top 40s in common. This makes sense to me. Bright lights and loud noises appeal to fairly basic instincts, and we are certainly drawn to them here.

But then, if you spin it again and look at the country from Boston's point of view, there's Portland Oregon, and San Francisco, and Seattle and New York and DC. I don't think you'd mistake Boston for John Mellencamp's "Small Town" for longer than a day. We wave the flags with enthusiasm, but then the cannons fire, and the last rockets leave the barges in the Charles, and before very long it's dark and quiet and north-eastern again, and we turn and walk back through the streets to our homes.

For amusement and curiosity, I calculated the 11th most popular song for every artist on Spotify, and then made a playlist of the most popular 1000 of these. This gives you a little sense of which artists get consistent attention beyond just their current hits.

And then, to go even deeper, I did it again with every artist's 100th most popular song.

And then, to go even deeper, I did it again with every artist's 100th most popular song.

| These Ones Go to 11

|

These Ones Go to 100

|

¶ Unfancy Machines · 10 June 2015 listen/tech

I spend a lot of time fiddling obsessively with the knobs on complicated music-discovery machines. I wouldn't do it if I didn't think it helped, and I spend a fair amount of that time pondering whether I'm confident that it's helping.

Your streaming music world is also about to be extra-complicated by more machinery for personalization, and I work on some of this, too. One clattering armada of machinery for trying to find music worth being discovered by somebody, and another one for trying to figure out which of that music is the music for which you are that somebody. It's kind of a wonder we can still hear over all that grinding.

Although, actually, it's less of a rhetorical wonder than an actual question. Can we hear over it? It's not inherently bad if your complicated thing is complicated, but it's bad if it's complicated and not better than something simpler. So in this spirit, I've added one more playlist to the end of The Needle, my array of emerging-song supposedly-discovering lists.

It is called The Straw. It is assembled by programmatically taking one track each from a random sample of 1000 or so of the both obscure and uncategorized releases from the current week's Spotify New-Release Sorting Hat.

There is no complicated scoring or optimizing or clustering, there is no personalization, there is no iteration or feedback or machine learning. Some of it probably isn't even new, or shouldn't have been uncategorized, or maybe shouldn't have been made. If my fancy machines are working, and if the underlying collectivist moral premise they implicitly represent -- that the world's listening patterns distinguish memorable music from forgettable -- has significant validity, then listening to this playlist should be a poor use of your time.

But those are non-trivial "if"s. If anybody claims that they do something mysterious and yet valuable, based on appealing but abstract assumptions, you ought to be able to demand that they, at least, have actually contemplated how the world would be if they didn't.

And this "they" is me, so here is my professional memento mori, an unfancy discovery engine that believes wholeheartedly, even when I have the courage to think I'm only pretending to, that to find amazing music you've never heard, all you need is a way to find music you've never heard.

Your streaming music world is also about to be extra-complicated by more machinery for personalization, and I work on some of this, too. One clattering armada of machinery for trying to find music worth being discovered by somebody, and another one for trying to figure out which of that music is the music for which you are that somebody. It's kind of a wonder we can still hear over all that grinding.

Although, actually, it's less of a rhetorical wonder than an actual question. Can we hear over it? It's not inherently bad if your complicated thing is complicated, but it's bad if it's complicated and not better than something simpler. So in this spirit, I've added one more playlist to the end of The Needle, my array of emerging-song supposedly-discovering lists.

It is called The Straw. It is assembled by programmatically taking one track each from a random sample of 1000 or so of the both obscure and uncategorized releases from the current week's Spotify New-Release Sorting Hat.

There is no complicated scoring or optimizing or clustering, there is no personalization, there is no iteration or feedback or machine learning. Some of it probably isn't even new, or shouldn't have been uncategorized, or maybe shouldn't have been made. If my fancy machines are working, and if the underlying collectivist moral premise they implicitly represent -- that the world's listening patterns distinguish memorable music from forgettable -- has significant validity, then listening to this playlist should be a poor use of your time.

But those are non-trivial "if"s. If anybody claims that they do something mysterious and yet valuable, based on appealing but abstract assumptions, you ought to be able to demand that they, at least, have actually contemplated how the world would be if they didn't.

And this "they" is me, so here is my professional memento mori, an unfancy discovery engine that believes wholeheartedly, even when I have the courage to think I'm only pretending to, that to find amazing music you've never heard, all you need is a way to find music you've never heard.