9 December 2024 to 29 September 2014 · tagged essay/listen

¶ Subgenres, subcontinents · 9 December 2024 essay/listen/tech

¶ Music and Football · 20 March 2024 essay/listen

Spotify's Loud and Clear site includes an analogy between musicians and football players, ostensibly to explain how "aspirations" to make money from creative/athletic pursuits are more widespread than actual career success.

This comparison is not original or unique to Spotify, and does make some limited sense. With both art and sports, you can choose to spend your time on them, and the process of making music or training for football is labor in the sense of requiring time and effort, but most of the people making this choice are not going to end up being financially compensated for their labor. A small minority are able to make a living from it, but you cannot join this minority simply by wanting.

The key difference between music streaming and football, however, is that in music, every stadium is Wembley.

If you are an amateur soccer player, you know that you are an amateur soccer player. You play on an amateur team, in an amateur league, probably with amateur referees in a random city park that has other uses the rest of the week. No matter how astonishing a goal you score, it is a goal in an amateur game in a park on Sunday.

In music, however, everybody plays in the same venue, nominally in the same league. Any song on any of the major commercial music-streaming services could be streamed 1 billion times tomorrow. Structurally, in the music version of football, an amateur player from a local park could kick a ball and it could slip past Caoimhin Kelleher in the 121st minute to send Liverpool crashing out of the FA Cup.

That game was at Old Trafford, not Wembley, but the point is that this mostly doesn't happen. The statistical economic dynamics of music and football are very similar, which is why the analogy presented itself in the first place. But the aspirations are exactly why it doesn't work. In football, not only do you know your current status, but you can see the potential future steps in your career, and how they might happen. You could impress a local scout with your park goal, and get a tryout for a local semi-pro team. You could lead the semi-pro league in assists and get signed for a year by a second-division team. You could captain your second-division team to promotion, and like a fairy-tale, three years later you are getting crushed 7-0 by Manchester City and trying to claw your way out of the relegation zone so your dream can continue just a little bit longer.

In music, there used to be a story like this. You played club gigs in your hometown, and gave demo tapes to your friends. Somebody who ran a local label maybe heard you and liked you enough to help you put out a record. Maybe that record got played on college radio a little, and got you a chance at a deal on a minor major label. Maybe your minor major-label debut had a minor hit. Maybe your label stuck with you and you got to make more records. Maybe your third album has a song about getting drunk alone in your hometown and introducing yourself again to your friend's mother and it blows up and suddenly you are playing in Wembley. Or Fenway Park, at least.

Streaming offers the tantalizing illusion that these laborious steps have been eliminated by technology. But really they haven't. Music is an attention economy. The dominance of the biggest attention companies used to be reinforced by constraints of physical distribution, but it mostly survives the format shift. Most of the songs on the biggest playlists still come from the three major labels.

Which doesn't mean that the story of your potential career hasn't changed. The new steps might involve playlists instead of clubs, viral videos instead of college radio, and maybe a judicious distribution deal instead of an old-school contract with an advance you will never recoup. And these new steps, if they happen, could happen more suddenly than the old steps, and thus it can feel like they could happen suddenly at any moment.

But, still, mostly they won't. Mostly the paths to big success still go through labels, particularly major ones. Mostly the old major-attention economy survives through minor adaptations. Whatever aspirations they have, or labor they expend, most of the 10 million artists on streaming services will never get beyond semi-professional status in the most marginal sense of "semi". I have songs on Spotify, too. They took labor to make. A few people have streamed them, and I have been paid a few cents for those streams. Last time I checked, my lifetime earnings from streaming music were well on the way to $5. From $4.

But I am an amateur. I know I'm an amateur, I'm not trying to make a living by making music. If streaming services all start imposing minimum stream-thresholds for royalty payouts, I may never get to that glittering $5 in the distance, and that will be morally disappointing but practically fine.

If you're trying to become a professional, it's not fine. If regressive thresholds take away your sense of progress, that's not fine. If the successes you aspire towards operate like lotteries, so that you can't work towards them, that's not fine. If the people who operate the economy in which you will or will not be able to make a living sound like they are dismissing you as a non-participant, that's not fine.

I like the football analogy, actually, but I think it applies the other way around: if you own a stadium, and you invite all the players in the world to come in and play in front of all the fans, you don't have to promise them all glory, but you better not try to tell them that some of their goals won't count.

This comparison is not original or unique to Spotify, and does make some limited sense. With both art and sports, you can choose to spend your time on them, and the process of making music or training for football is labor in the sense of requiring time and effort, but most of the people making this choice are not going to end up being financially compensated for their labor. A small minority are able to make a living from it, but you cannot join this minority simply by wanting.

The key difference between music streaming and football, however, is that in music, every stadium is Wembley.

If you are an amateur soccer player, you know that you are an amateur soccer player. You play on an amateur team, in an amateur league, probably with amateur referees in a random city park that has other uses the rest of the week. No matter how astonishing a goal you score, it is a goal in an amateur game in a park on Sunday.

In music, however, everybody plays in the same venue, nominally in the same league. Any song on any of the major commercial music-streaming services could be streamed 1 billion times tomorrow. Structurally, in the music version of football, an amateur player from a local park could kick a ball and it could slip past Caoimhin Kelleher in the 121st minute to send Liverpool crashing out of the FA Cup.

That game was at Old Trafford, not Wembley, but the point is that this mostly doesn't happen. The statistical economic dynamics of music and football are very similar, which is why the analogy presented itself in the first place. But the aspirations are exactly why it doesn't work. In football, not only do you know your current status, but you can see the potential future steps in your career, and how they might happen. You could impress a local scout with your park goal, and get a tryout for a local semi-pro team. You could lead the semi-pro league in assists and get signed for a year by a second-division team. You could captain your second-division team to promotion, and like a fairy-tale, three years later you are getting crushed 7-0 by Manchester City and trying to claw your way out of the relegation zone so your dream can continue just a little bit longer.

In music, there used to be a story like this. You played club gigs in your hometown, and gave demo tapes to your friends. Somebody who ran a local label maybe heard you and liked you enough to help you put out a record. Maybe that record got played on college radio a little, and got you a chance at a deal on a minor major label. Maybe your minor major-label debut had a minor hit. Maybe your label stuck with you and you got to make more records. Maybe your third album has a song about getting drunk alone in your hometown and introducing yourself again to your friend's mother and it blows up and suddenly you are playing in Wembley. Or Fenway Park, at least.

Streaming offers the tantalizing illusion that these laborious steps have been eliminated by technology. But really they haven't. Music is an attention economy. The dominance of the biggest attention companies used to be reinforced by constraints of physical distribution, but it mostly survives the format shift. Most of the songs on the biggest playlists still come from the three major labels.

Which doesn't mean that the story of your potential career hasn't changed. The new steps might involve playlists instead of clubs, viral videos instead of college radio, and maybe a judicious distribution deal instead of an old-school contract with an advance you will never recoup. And these new steps, if they happen, could happen more suddenly than the old steps, and thus it can feel like they could happen suddenly at any moment.

But, still, mostly they won't. Mostly the paths to big success still go through labels, particularly major ones. Mostly the old major-attention economy survives through minor adaptations. Whatever aspirations they have, or labor they expend, most of the 10 million artists on streaming services will never get beyond semi-professional status in the most marginal sense of "semi". I have songs on Spotify, too. They took labor to make. A few people have streamed them, and I have been paid a few cents for those streams. Last time I checked, my lifetime earnings from streaming music were well on the way to $5. From $4.

But I am an amateur. I know I'm an amateur, I'm not trying to make a living by making music. If streaming services all start imposing minimum stream-thresholds for royalty payouts, I may never get to that glittering $5 in the distance, and that will be morally disappointing but practically fine.

If you're trying to become a professional, it's not fine. If regressive thresholds take away your sense of progress, that's not fine. If the successes you aspire towards operate like lotteries, so that you can't work towards them, that's not fine. If the people who operate the economy in which you will or will not be able to make a living sound like they are dismissing you as a non-participant, that's not fine.

I like the football analogy, actually, but I think it applies the other way around: if you own a stadium, and you invite all the players in the world to come in and play in front of all the fans, you don't have to promise them all glory, but you better not try to tell them that some of their goals won't count.

¶ Make Streaming (Listeners) Pay · 12 March 2024 essay/listen

I like legislation as a tool for social change, so I'm positively predisposed towards the Living Wage for Musicians Act as a tactic, and I agree with its goal of making it possible for more people to make better livings as musicians.

But I don't think this proposed law, as written, will work.

Here's how it would operate:

Music-streaming subscriptions in the US would have a federal government fee of 50% added to them...

This ought to be in the headline of every article covering this story. "Make Streaming Pay", the UMAW slogan for this effort, sounds like a vendetta against streaming services, especially coming from the same people who brought us "Justice at Spotify" previously, but as a music listener you should understand that the people who would pay this time are you. The proposed bill would add fees to music subscriptions. Fees are a well-established tactic, but not exactly a well-loved one. It's at least faintly ironic that Congress is scrutinizing Ticketmaster's excessive fees at the same time that this bill is proposing to add one to music streaming.

And 50% is a lot. A $10.99/month subscription would get an added $5.50 government fee, raising the total to $16.49. The bill even specifies a minimum of $4, so a $5.99 student subscription would rise to $9.99. While I don't think either of those are unreasonable prices for all the music in the world, they're giant relative jumps. I would fully expect them to be publicly unpopular as a proposal, and thus hard to find support for in Congress. If enacted, they would probably cause many existing subscribers to downgrade to free (ad-supported) alternatives. Enough people doing so could cancel out the monetary benefit, so this should not be proposed without careful modeling of likely price flexibility. I doubt that has been done, and certainly no evidence of it has been presented by the bill's advocates. I would also expect most or all streaming services to lobby vigorously against this change because of these effects, even though the fee itself is not paid by them. Except...

and music-streaming services would have a 10% tax on their "non-subscription" (meaning mainly advertising) revenue in the US...

You can't add fees to free, so here's the other half of the plan. Most streaming services already pay ~70% of revenue to licensors, keeping ~30% for themselves. A 10% tax on revenue thus cuts gross advertising profit by a third. Since Spotify (whom I single out here only because as a public company they report music-specific financial results, which Apple/Amazon/YouTube Music as divisions of larger companies do not) has mostly not turned a net profit at all, this proposed tax will almost certainly be taken as intractably punitive, and I expect all the services with ad-supported tiers to resist it. Spotify probably cannot afford to threaten to pull out of the US like it threatened to pull out of Uruguay when a (different) version of this idea was proposed there, and would presumably not want to increase their own prices again having only recently raised them in most countries, making it hard to take the tactic they are taking in response to a 1.2% tax in France. So I would expect Spotify to lobby against this as if it is an existential threat.

There's also a very important question here about what constitutes a music service, and in particular whether YouTube (not YouTube Music) and TikTok count. The bill doesn't address this, although the UMAW advocacy for it strongly implies that YouTube, at least, is meant to be included. I do not expect Google to quietly accept a 10% tax on any meaningful subset of YouTube advertising revenue.

which would be collected into (and by) a new government fund/agency...

Streaming music royalties are already split into three different components: to licensors, to publishers (for songwriters), and to performing-rights agencies (also for songwriters; it's a long story). This bill would add a fourth. That seems to me like the wrong direction, and grounds for skepticism even before we get into how the new fund would work. As an example it also implies that every country would need to create a similar fund of their own, although the bill as written seems to ignore the fact that it applies to the flow of money in only one country, while the music itself is global.

which would also collect and tabulate monthly streams by unique master recording...

This detail is unexplicated in the bill, but introduces a very serious technical requirement. Music is delivered to streaming services by licensors in releases composed of tracks, and it's normal for there to end up being many different tracks that have the same original audio, e.g. a single and that same song on the subsequent album and the same song again later on a compilation, and all these again in many different countries. Reconciling these requires audio-analysis software that can correctly match two tracks of the same recording even if they've gone through slightly different processing, and correctly differentiate between two different pieces of music even if they contain substantial similarity (like a song and a remix of it that adds a guest verse). And even after you've correctly matched tracks by their audio, their credits might differ, so you have to figure out which credits you're going to use. I can testify from 12 years of involvement with the process at the Echo Nest and Spotify that this is all not a trivial problem, and can be error prone even in a long-running production system. The administrators of the new fund are going to have to hire more programmers than they probably realize.

impose a cap of 1 million streams/month on each such recording...

This is arguably the most critical, progressive and interesting detail in the bill. Rather than just increasing all artists' current income by a small proportional amount, the bill attempts to specifically support artists who might not currently be making a living from their music, by effectively redirecting some or most of the money from songs with >1m streams back into the payment pool. This is why the recording-matching has to be accurate, but sadly is also the key to trivial manipulation of this scheme to evade its intent. Each detected "unique recording" is subject to a 1m cap, but it's not hard to produce multiple tracks that sound the same to listeners, but intentionally defeat the usual methods for automatic matching. Were this bill to be passed, I expect it would become normal practice to do this across releases and services, to make every track of the same recording register uniquely, so that each one gets its own 1m cap. The producers of very popular songs would have a strong incentive to also try to do it over time for each song during a given month, hoping to accumulate N million streams 1m at a time across N variations of the same song.

The 1-million-stream threshold here is arbitrary. The bill itself doesn't justify or explain it. Rep. Tlaib has mentioned in speaking about this bill that it takes 800,000 streams/month at a current average rate of $.003/stream to make the equivalent of minimum wage, which is correct math, but that's per artist, not per track. The unavoidable market truth about music (like most non-commissioned art) is that financial reward is not a function of quantity of labor. You can spend any amount of time making a song, and maybe nobody will play it. If we really want, as a society, to give people a living wage for the labor of making music, as opposed to lucking into popularity, then we need to spend our government energies on grants or Universal Basic Income, not on streaming taxes and fees.

and then divide payments proportionally by capped streams...

This sounds like just unremarkable process, but is sneakily the most serious flaw of the whole bill as written. The fund combines all streams from all services, and all money from all services, and distributes that combined money according to those combined streams. This sounds like the pro rata royalty-allocation method already in use by all major streaming services. The crucial difference, though, is that services do not do this with one big pool of money and streams, they do it with an individual pool of money and streams for each payment plan (in each country). This is essential, because the revenue per listener varies widely across countries and plans. A stream from a Spotify Premium subscriber in Iceland is worth considerably more than a stream from an ad-supported listener in India.

By combining all the streams and all the money, this plan would make it possible to use the cheapest form of artificial streaming to accumulate fraudulent streams that would share money from the most expensive ones, thus inaugurating a golden age of streaming fraud.

This is not only a fatal flaw of the bill as written, it's one that reveals that the writers of the bill do not know how the existing royalty methods work, and didn't consult with anybody who does.

90% to "featured" artists and 10% to "non-featured" artists...

It's a minor selling point of this bill that it would result in some royalties being paid to "non-featured" artists, like session musicians and backing vocalists, who do not (usually) get royalties at all from the current system. The amount is small, though, and administering it would be a procedural headache. Because those people don't currently get paid royalties, their participation isn't necessarily included in the licensors' metadata. And, conversely, because those people don't get royalties, they're currently mostly paid for their work in old-fashioned wages. Give them a share of the royalties and we might find that that becomes an excuse to pay them less up front, in the same way that tip workers are often given lower base wages.

The bill does not say how royalties would be split between multiple featured or non-featured artists. I guess it's loosely implied that it would automatically be equal shares to each, since there's no mention of any mechanism to specify otherwise. The bill does specify that "artists" means individual humans, not corporations or generative AIs (!), which seems to mean that bands are not part of this scheme, only each person one at a time.

And, notably, the bill as written specifically does not include songwriters. This is a little surprising to me, since I think of advocacy for higher royalty rates for songwriters as part of the same family of social-justice causes as higher royalty rates for performers, and songwriters get the smallest share of royalties in the current system. I'm not looking forward to the antagonism between "performers" and "songwriters" that this omission might provoke.

who sign up with the fund and provide payment information.

This, too, is both a distinguishing characteristic of this plan and a drawback. The whole point of this fourth royalty scheme is to route it around the first three, although in practice it's mainly the payment of recording royalties to licensors (and thus to labels) that the writers are trying to avoid. Labels, particularly major ones, often write artist contracts in which advances are paid up front, and artists not only get a small percentage of the royalties later, but even that small percentage is accounted for as repaying the advance as a loan. So an artist might, in practice, get no royalties for a while, or ever. (Although, again, they were paid an advance, and if their royalties don't earn back the advance, they don't have to repay it any other way.)

But, of course, you don't have to sign a label contract in order to release music on streaming services. DIY distributors either charge small flat fees, or take very small shares of your royalties. But labels provide services in addition to taking royalties (and paying advances), and maybe you want those. I suspect that musicians signed to major labels are mostly doing OK, at least temporarily during their maybe-short label tenure. And if they aren't, and their label contracts are why, maybe that's where the laws should be pointed.

But that means this fund is yet another thing an artist has to sign up for and manage, and which in turn has to manage and verify them. I have not found any good estimates of how many artists currently do not do the work to register their songs to collect performance and mechanical rights, and how often there are contradictions between ownership claims, but I'm sure both are common. There's precedent in performance-rights organizations for international cooperation, but I don't know if any of those operate on this scale, and even if they do, this bill doesn't propose to use them, so this new fund (and its equivalents in other countries, if they exist) would have to reinvent all of that process.

The stipulation about individuals, not companies, seems obviously like a preemptive attempt to keep labels from registering on their artists' "behalf" and collecting this new windfall too, but I'm not immediately convinced that won't happen somehow anyway. And indeed it might have to for the scheme to accommodate the estates of dead artists, whom I assume it doesn't intend to exclude.

Even if we imagine that nobody attempts to evade this rule, though, the existence of a fourth royalty that bypasses labels is likely to push labels, and the three major-label companies in particular, to object to this bill too. And were it enacted, I would expect to see labels begin to change the terms of their contracts to reduce or eliminate artist shares of the recording royalties since they're now supposedly getting this new Living Wage paid separately.

The notable thing this bill does not include is any mechanism or support for this claim that the UMAW, who collaborated on it, continue to make here:

Nor have I seen any explanation of why the suspiciously round penny is coincidentally the magic living-wage level, and I'm willing to bet a large number of pennies that no such explanation exists. There are many very-good bands who do not have 1 million streams total, all time, across all their songs on Spotify. That's not a multi-year living wage for a group of people even at a dime per stream.

But OK, it's easy to criticize. If I'm in favor of laws, and I share the goal of improving the lives of musicians, what should we do instead?

When in doubt, try to remove imbalances of power. Reduce complexity, reduce secrecy. Personally, I would start by trying to simplify and improve the existing royalty process, rather than adding another incompletely-thought out layer with uncertain consequences.

We got a good idea about how to do this, by accident, recently, when Spotify and Deezer and UMG collaborated to change their contractual rules for recording royalties to pay nothing to tracks that don't reach 1,000 streams over the course of the last year. This is a regressive measure I personally despise, but the interesting part is that they actually couldn't pay those songs nothing, because the performance and mechanical rates are set by law (at least in the US). If the recording rates were also set by law, those wouldn't have been subject to secret contract negotiations either. Moving all the rates into law would also allow them to be determined (and debated in public) as a coherent set, which would make a lot more sense. And while we're at it, we could eliminate the spurious performance royalties, reducing the number of royalty components to two, one for the performers and one for the songwriters. And, in fact, if we allowed artists to designate original songs, so that this information was passed on by licensors to streaming services, then both royalties could be paid at once for those tracks, reducing the reporting overhead for artists and services both, and recovering some of the money currently lost on the way to artists who never took the time to sign up for BMI or ASCAP.

Those simplifications would not, in themselves, provide a predictable living wage for all working musicians, either. But they would make the current streaming model less mysterious, and less beholden to secret agreements between a few giant corporations. Plenty more work would remain to be done. But that work would be easier think about, and easier to do. And less likely to produce earnest laws that probably have no chance of living up to their authors' hopes for them, or ours.

But I don't think this proposed law, as written, will work.

Here's how it would operate:

Music-streaming subscriptions in the US would have a federal government fee of 50% added to them...

This ought to be in the headline of every article covering this story. "Make Streaming Pay", the UMAW slogan for this effort, sounds like a vendetta against streaming services, especially coming from the same people who brought us "Justice at Spotify" previously, but as a music listener you should understand that the people who would pay this time are you. The proposed bill would add fees to music subscriptions. Fees are a well-established tactic, but not exactly a well-loved one. It's at least faintly ironic that Congress is scrutinizing Ticketmaster's excessive fees at the same time that this bill is proposing to add one to music streaming.

And 50% is a lot. A $10.99/month subscription would get an added $5.50 government fee, raising the total to $16.49. The bill even specifies a minimum of $4, so a $5.99 student subscription would rise to $9.99. While I don't think either of those are unreasonable prices for all the music in the world, they're giant relative jumps. I would fully expect them to be publicly unpopular as a proposal, and thus hard to find support for in Congress. If enacted, they would probably cause many existing subscribers to downgrade to free (ad-supported) alternatives. Enough people doing so could cancel out the monetary benefit, so this should not be proposed without careful modeling of likely price flexibility. I doubt that has been done, and certainly no evidence of it has been presented by the bill's advocates. I would also expect most or all streaming services to lobby vigorously against this change because of these effects, even though the fee itself is not paid by them. Except...

and music-streaming services would have a 10% tax on their "non-subscription" (meaning mainly advertising) revenue in the US...

You can't add fees to free, so here's the other half of the plan. Most streaming services already pay ~70% of revenue to licensors, keeping ~30% for themselves. A 10% tax on revenue thus cuts gross advertising profit by a third. Since Spotify (whom I single out here only because as a public company they report music-specific financial results, which Apple/Amazon/YouTube Music as divisions of larger companies do not) has mostly not turned a net profit at all, this proposed tax will almost certainly be taken as intractably punitive, and I expect all the services with ad-supported tiers to resist it. Spotify probably cannot afford to threaten to pull out of the US like it threatened to pull out of Uruguay when a (different) version of this idea was proposed there, and would presumably not want to increase their own prices again having only recently raised them in most countries, making it hard to take the tactic they are taking in response to a 1.2% tax in France. So I would expect Spotify to lobby against this as if it is an existential threat.

There's also a very important question here about what constitutes a music service, and in particular whether YouTube (not YouTube Music) and TikTok count. The bill doesn't address this, although the UMAW advocacy for it strongly implies that YouTube, at least, is meant to be included. I do not expect Google to quietly accept a 10% tax on any meaningful subset of YouTube advertising revenue.

which would be collected into (and by) a new government fund/agency...

Streaming music royalties are already split into three different components: to licensors, to publishers (for songwriters), and to performing-rights agencies (also for songwriters; it's a long story). This bill would add a fourth. That seems to me like the wrong direction, and grounds for skepticism even before we get into how the new fund would work. As an example it also implies that every country would need to create a similar fund of their own, although the bill as written seems to ignore the fact that it applies to the flow of money in only one country, while the music itself is global.

which would also collect and tabulate monthly streams by unique master recording...

This detail is unexplicated in the bill, but introduces a very serious technical requirement. Music is delivered to streaming services by licensors in releases composed of tracks, and it's normal for there to end up being many different tracks that have the same original audio, e.g. a single and that same song on the subsequent album and the same song again later on a compilation, and all these again in many different countries. Reconciling these requires audio-analysis software that can correctly match two tracks of the same recording even if they've gone through slightly different processing, and correctly differentiate between two different pieces of music even if they contain substantial similarity (like a song and a remix of it that adds a guest verse). And even after you've correctly matched tracks by their audio, their credits might differ, so you have to figure out which credits you're going to use. I can testify from 12 years of involvement with the process at the Echo Nest and Spotify that this is all not a trivial problem, and can be error prone even in a long-running production system. The administrators of the new fund are going to have to hire more programmers than they probably realize.

impose a cap of 1 million streams/month on each such recording...

This is arguably the most critical, progressive and interesting detail in the bill. Rather than just increasing all artists' current income by a small proportional amount, the bill attempts to specifically support artists who might not currently be making a living from their music, by effectively redirecting some or most of the money from songs with >1m streams back into the payment pool. This is why the recording-matching has to be accurate, but sadly is also the key to trivial manipulation of this scheme to evade its intent. Each detected "unique recording" is subject to a 1m cap, but it's not hard to produce multiple tracks that sound the same to listeners, but intentionally defeat the usual methods for automatic matching. Were this bill to be passed, I expect it would become normal practice to do this across releases and services, to make every track of the same recording register uniquely, so that each one gets its own 1m cap. The producers of very popular songs would have a strong incentive to also try to do it over time for each song during a given month, hoping to accumulate N million streams 1m at a time across N variations of the same song.

The 1-million-stream threshold here is arbitrary. The bill itself doesn't justify or explain it. Rep. Tlaib has mentioned in speaking about this bill that it takes 800,000 streams/month at a current average rate of $.003/stream to make the equivalent of minimum wage, which is correct math, but that's per artist, not per track. The unavoidable market truth about music (like most non-commissioned art) is that financial reward is not a function of quantity of labor. You can spend any amount of time making a song, and maybe nobody will play it. If we really want, as a society, to give people a living wage for the labor of making music, as opposed to lucking into popularity, then we need to spend our government energies on grants or Universal Basic Income, not on streaming taxes and fees.

and then divide payments proportionally by capped streams...

This sounds like just unremarkable process, but is sneakily the most serious flaw of the whole bill as written. The fund combines all streams from all services, and all money from all services, and distributes that combined money according to those combined streams. This sounds like the pro rata royalty-allocation method already in use by all major streaming services. The crucial difference, though, is that services do not do this with one big pool of money and streams, they do it with an individual pool of money and streams for each payment plan (in each country). This is essential, because the revenue per listener varies widely across countries and plans. A stream from a Spotify Premium subscriber in Iceland is worth considerably more than a stream from an ad-supported listener in India.

By combining all the streams and all the money, this plan would make it possible to use the cheapest form of artificial streaming to accumulate fraudulent streams that would share money from the most expensive ones, thus inaugurating a golden age of streaming fraud.

This is not only a fatal flaw of the bill as written, it's one that reveals that the writers of the bill do not know how the existing royalty methods work, and didn't consult with anybody who does.

90% to "featured" artists and 10% to "non-featured" artists...

It's a minor selling point of this bill that it would result in some royalties being paid to "non-featured" artists, like session musicians and backing vocalists, who do not (usually) get royalties at all from the current system. The amount is small, though, and administering it would be a procedural headache. Because those people don't currently get paid royalties, their participation isn't necessarily included in the licensors' metadata. And, conversely, because those people don't get royalties, they're currently mostly paid for their work in old-fashioned wages. Give them a share of the royalties and we might find that that becomes an excuse to pay them less up front, in the same way that tip workers are often given lower base wages.

The bill does not say how royalties would be split between multiple featured or non-featured artists. I guess it's loosely implied that it would automatically be equal shares to each, since there's no mention of any mechanism to specify otherwise. The bill does specify that "artists" means individual humans, not corporations or generative AIs (!), which seems to mean that bands are not part of this scheme, only each person one at a time.

And, notably, the bill as written specifically does not include songwriters. This is a little surprising to me, since I think of advocacy for higher royalty rates for songwriters as part of the same family of social-justice causes as higher royalty rates for performers, and songwriters get the smallest share of royalties in the current system. I'm not looking forward to the antagonism between "performers" and "songwriters" that this omission might provoke.

who sign up with the fund and provide payment information.

This, too, is both a distinguishing characteristic of this plan and a drawback. The whole point of this fourth royalty scheme is to route it around the first three, although in practice it's mainly the payment of recording royalties to licensors (and thus to labels) that the writers are trying to avoid. Labels, particularly major ones, often write artist contracts in which advances are paid up front, and artists not only get a small percentage of the royalties later, but even that small percentage is accounted for as repaying the advance as a loan. So an artist might, in practice, get no royalties for a while, or ever. (Although, again, they were paid an advance, and if their royalties don't earn back the advance, they don't have to repay it any other way.)

But, of course, you don't have to sign a label contract in order to release music on streaming services. DIY distributors either charge small flat fees, or take very small shares of your royalties. But labels provide services in addition to taking royalties (and paying advances), and maybe you want those. I suspect that musicians signed to major labels are mostly doing OK, at least temporarily during their maybe-short label tenure. And if they aren't, and their label contracts are why, maybe that's where the laws should be pointed.

But that means this fund is yet another thing an artist has to sign up for and manage, and which in turn has to manage and verify them. I have not found any good estimates of how many artists currently do not do the work to register their songs to collect performance and mechanical rights, and how often there are contradictions between ownership claims, but I'm sure both are common. There's precedent in performance-rights organizations for international cooperation, but I don't know if any of those operate on this scale, and even if they do, this bill doesn't propose to use them, so this new fund (and its equivalents in other countries, if they exist) would have to reinvent all of that process.

The stipulation about individuals, not companies, seems obviously like a preemptive attempt to keep labels from registering on their artists' "behalf" and collecting this new windfall too, but I'm not immediately convinced that won't happen somehow anyway. And indeed it might have to for the scheme to accommodate the estates of dead artists, whom I assume it doesn't intend to exclude.

Even if we imagine that nobody attempts to evade this rule, though, the existence of a fourth royalty that bypasses labels is likely to push labels, and the three major-label companies in particular, to object to this bill too. And were it enacted, I would expect to see labels begin to change the terms of their contracts to reduce or eliminate artist shares of the recording royalties since they're now supposedly getting this new Living Wage paid separately.

The notable thing this bill does not include is any mechanism or support for this claim that the UMAW, who collaborated on it, continue to make here:

The Living Wage for Musicians Act is built to pay artists a minimum penny per stream, an amount calculated specifically to provide a working class artist a living wage from streaming.The bill, as written, is very definitely not "built" to pay $.01/stream. UMAW's intro puts the current average stream rate at $0.00173 (including YouTube), and after an hour or so of spreadsheet noodling I could not see any way it would more than double this for the biggest beneficiaries (artists whose tracks all approach 1m streams without going over), even if nothing else in the industry changed in reaction. That would be $0.00346/stream, still a long way from $0.01. It doesn't help my confidence in UMAW's math diligence that their "calculator" to show the effects of this bill not only just multiplies streams by $0.01, but doesn't even bother to apply the 1m-stream cutoff.

Nor have I seen any explanation of why the suspiciously round penny is coincidentally the magic living-wage level, and I'm willing to bet a large number of pennies that no such explanation exists. There are many very-good bands who do not have 1 million streams total, all time, across all their songs on Spotify. That's not a multi-year living wage for a group of people even at a dime per stream.

But OK, it's easy to criticize. If I'm in favor of laws, and I share the goal of improving the lives of musicians, what should we do instead?

When in doubt, try to remove imbalances of power. Reduce complexity, reduce secrecy. Personally, I would start by trying to simplify and improve the existing royalty process, rather than adding another incompletely-thought out layer with uncertain consequences.

We got a good idea about how to do this, by accident, recently, when Spotify and Deezer and UMG collaborated to change their contractual rules for recording royalties to pay nothing to tracks that don't reach 1,000 streams over the course of the last year. This is a regressive measure I personally despise, but the interesting part is that they actually couldn't pay those songs nothing, because the performance and mechanical rates are set by law (at least in the US). If the recording rates were also set by law, those wouldn't have been subject to secret contract negotiations either. Moving all the rates into law would also allow them to be determined (and debated in public) as a coherent set, which would make a lot more sense. And while we're at it, we could eliminate the spurious performance royalties, reducing the number of royalty components to two, one for the performers and one for the songwriters. And, in fact, if we allowed artists to designate original songs, so that this information was passed on by licensors to streaming services, then both royalties could be paid at once for those tracks, reducing the reporting overhead for artists and services both, and recovering some of the money currently lost on the way to artists who never took the time to sign up for BMI or ASCAP.

Those simplifications would not, in themselves, provide a predictable living wage for all working musicians, either. But they would make the current streaming model less mysterious, and less beholden to secret agreements between a few giant corporations. Plenty more work would remain to be done. But that work would be easier think about, and easier to do. And less likely to produce earnest laws that probably have no chance of living up to their authors' hopes for them, or ours.

¶ Talking to Robots About Songs and Memory and Death (PopCon 2024) · 7 March 2024 essay/listen

Talking to Robots About Songs and Memory and Death

Infinite Archives, Fluctuating Access and Flickering Nostalgia at the Dawn of the Age of Streaming Music

(delivered at the 2024 Pop Conference)

Let me tell you how it used to be. Songs were written and sung and recorded, but then they were encased in finite increments of plastic, and our control over our ability to hear them relied on each of us, sometimes in competition, acquiring and retaining these tokens. The scarcity of particular plastic could shroud songs in selective silence. A basement flood could wash away music.

Imagine, instead, a shared and living archive. Music, instead of being carved into inert plastic, is infused into the frenetic dreams of angelic synapses. Every song is sung at once in waiting, and needs only your curious attention to summon it back into the air. Nothing, once heard, need ever be lost. The rising seas might drive us to higher ground, but our songs watch over us from above.

When I proposed this talk, Spotify held 368,660,954 tracks from 61,096,319 releases, and I could know that because I worked there. The servers of streaming music services are unprecedented cultural repositories, diligently maintained and fairly well annotated. We pour our love into them, and in return we can get it back any time we want.

That's the techno-utopian version, at least. In the real-life version, the angels are only robots, and the robots aren't even actual robots. The infinite generosity of technology is constrained by relentless pragmatic contingencies: corporations, laws, contracts, stockholders, greed. All those songs are there, technically poised, but whether we are allowed to hear them depends on layers of human abstraction and distraction. This is what people mean when they object to streaming as renting the things that you love. The erratic logistics of music licensing control whether any given song is permitted to escape from the streaming servers. Licensing, in turn, is permuted by artists and labels and distributors and streaming services, and then again by the borders of countries and the passage of time. The song you want to hear again is still there. But that may not be enough.

"Renting the things you love" sounds bad. But so too, I think, does "purchasing the things you love". I don't philosophically need or want my love to be materialized in a form for which I have to transact, and which I then have to store. I want to be able to recall joys effortlessly. The system model of instant magical recall, which is an illusion that streaming can sustain under conducive network conditions, is what I think we want, what music wants. If renting is reliable, maybe it's fine. But how reliable is it?

If you don't work for a streaming service, you can only really assess this by anecdote. Joni Mitchell objected to Spotify's podcast deal with Joe Rogan, and revoked its rights to her whole catalog. Because rights are complicated, though, it didn't entirely work. When I proposed this talk, there was one Joni Mitchell song still accessible on Spotify in the US, a stray copy of "A Case of You" from a random compilation released in roundabout evasion by some label other than hers. If you didn't know this context, you would have no immediate way to tell Joni wasn't an emerging artist with just the one complicated, hopeful first single so far. A complicated hopeful first single with 103,102,704 plays, apparently, so you might wonder a little bit. Promising, I think. I'd like to hear more.

Since then, the license police caught up to that rogue compilation, and "A Case of You" is gone again. As of my drafting of this talk, Joni Mitchell's Spotify catalog was a 10-song 1970 BBC live album, and a single pointlessly overbearing cover of "River" by somebody else that was gamed onto Joni's Spotify page by the trick of labeling it as a classical composition, which causes Spotify to treat its composer as one of its primary artists. If the only artists with the power to withhold their songs were ones of Joni's stature, that would actually be fairly manageable. The plastic tokens of Blue are not scarce or expensive. If only artists had the power to withhold songs, actually, this would be a conversation about art and the limits of authorial control, and whether Joni is allowed to come take your copy of Blue away from you if you listen to Joe Rogan.

If you do work for a streaming service, though, and you can manage not to resign in protest of anything it does that you disagree with, then you don't have to rely on annecdote, you can use data. So I did. I ran the historical analysis of all post-release licensing gaps in song availability from 2015 to 2023, both overall and aggregated by licensor. In practice, in turns out, almost all songs available today have been available for streaming continuously since release. There are a handful of licensors whose tracks are routinely retracted, and there are good reasons for this, which I'm not allowed to tell you but I can reassure you that those are not the tracks we're worried about. Actual licensing gaps for actual songs with actual audiences are, statistically speaking, vanishingly rare. I made a nice graph of this.

If you work for a streaming service, however, you can also get laid off by that streaming service, which I also did. When this happens you have a surprise 10-minute call with an HR rep you've never seen before at 9:15 on a Monday morning, and then your laptop is remote-locked and you don't have those graphs any more. The robots are not allowed to talk to me now. Who will sit with them when they are sad? The problem with externalizing our memories and our note-taking into the cloud isn't technological reliability, it's control. The problem with renting the things you love is not the fragility of the things, it's the morally unregulated fragility of the relationship between you and the corporate angels.

We'll be OK without that graph. It was not, shall we say, the "A Case of You" of data graphics. The things that really belonged to Spotify, Spotify can keep. The goverance models for modern corporations are still painfully primitive. We understand that local democracies and a little bit of international law are a better model than crusader feudalism for communities of place, and I feel like it's morally apparent that corporations, as communities of purpose, ultimately deserve the same models and protections. If you move away from a city, you're still allowed to come visit. I should probably be allowed to visit my graphs. I like to imagine Joni ripping copies of her own CDs and adding them to Spotify as local files just as a jurisdiction flex.

My listening, on the other hand, is my own. Consumer protections are slightly more advanced than employee protections, so you can request your complete listening history from Spotify any time you want. For much of the decade I spent working at Spotify, though, I also maintained an abstruse weekly annotated-playlist series called New Particles, so I have my own record, not just of what I heard, but what I cared about. Over the course of 454 weeks, I cared about 35,900 tracks by 13,951 different artists. This is small for data, but big for annecdotes. What I find, going through it, is that almost every week beyond the recent past has at least one song that is now, or at least currently, unavailable. Some of the earliest lists from 2015 are missing 3 or 4, but by 2017 and 2018 it's usually 1, plus or minus 1.

Counting is not an emotional exercise, though, and all interesting music-data experiments begin with some kind of counting but don't stop there. So I went through the playlists I was listening to in my birthday week each year, cross-checking the specific tracks that had gone gray in Spotify, to see if I could tell a) how missing they really are, and b) how much I care. This is mostly what my job at Spotify was like, too: short bursts of math, and then the long curious process of trying to understand the significance of the resulting numbers. And I did consistently say that I would be doing this even if they weren't paying me.

From my March 31st 2015 list I am missing the song "Kranichstil" by the Ukrainian/German rapper Olexesh. His albums before and after seem to all be available for streaming still. This one isn't, but the song is easily found on YouTube. It's still sinuous and boomy and great.

2016: I'm missing "Rolling Stone" by the Pennsylvania emocore duo I Am King. They're still putting out sporadic emo covers of pop songs, which is one of my numerous weaknesses. "Rolling Stone" was an original, and I admit I don't remember it super-well, so maybe the version that is currently available on Spotify is different from the unavailable one I liked in 2016, but it's definitely close enough.

2017: "Por Amor" by the Chilean modern-rock band Lucybell. I had the single of this on my playlist, and you can't play that any more, but the slightly longer version is still the first track on the readily-available album Magnético, and still sounds like a stern Spanish arena-rock transformation of a New Order song.

2018: The whole album MASSIVE by the K-Pop boy-band B.A.P. is unavailable, but the song I liked, the cartoonish rap-rock rant "Young, Wild and Free", was originally on a 2015 EP, which is still available.

2019: The trap-metal noise-blast "HeavyMetal!" (no space between the words, exclamation point at the end) by 7xvn (spelled with the number seven, then x-v-n) is off of Spotify, but you can still find it on Soundcloud, which in this case feels about right.

2020: A gothic metalish song called "Menneisyyden Haamut" by the Finnish band Alter Noir. Their Spotify page is empty now, and if you Google this song, the results are the orphaned Spotify page, two links from their own Facebook page to that empty Spotify page, and then my playlist that I put the song on. I sent myself an email to see if I knew what the story is with this, but I haven't heard back from myself yet.

2021: "Fuck You Nnb" by lieu. I am old and do not know what "Nnb" stood for, but I do know that lieu was supposedly a 15-year-old kid deliberately switching between distributors so their songs would end up strewn across disconnected artist identities. Perfect public memory of what we thought was a good idea when we were 15 is not necessarily a civic virtue. In some cases forgetting is probably the right way to remember.

2022: ANISFLE were an ornate Japanese rock band, or at least a heavily embroidered impression of one. Their Spotify profile is blank, their web store is empty, I guess something catastrophic happened to them. But there are still a few of their videos on YouTube, and they're still ridiculous and magnificent.

2023: The only new thing I loved last April 4th that didn't even survive for a year was a maskandi song called "UYASANGANA YINI" by uMjikelwa. It seems to still be available on Apple Music. One of his other albums is on Spotify, and I will be completely honest that although I adore maskandi and follow hundreds of maskandi artists to make sure I have a constant supply of new maskandi to listen to, I usually pick one random song from each album and I do not pretend I can really tell them apart. If you snuck into my web archives and swapped this for anything similar, I would almost certainly not notice.

I think I can live with that much loss. Individual human obstruction occludes individual archives, but the network of archives, from the well-regulated to the unruly, tends to route around suppression. It's hard to make everybody forget.

And meanwhile, my database memory is far, far better than my brain memory. How many of those 13,951 artists could I list without looking? Some. Lots, but not most. But this is how I live, now. How old was my kid when we had the birthday party where their best friend's brother fell on a brick and had to be taken to the ER? I don't remember, but I can look through Google Photos and find it by the pictures we took before the panic. Which China Mieville book did I read first? I don't remember, but I bet I can find the email I wrote you right afterwards. Or maybe I sent it from a work address and so I can't.

So yes, our technically perfect externalized memories are imperfected by our insistence on staging them behind our contentious and fluctuating rules. We produce a compromised projection of our archives by fighting over their access controls. Our human systems hold back our information systems.

But I think we'd rather have that than the other way around. If my record store, in 1989, had made a ridiculous deal with Joe Rogan and Joni had pulled her whole divider out of the M bins, we had no collective recourse. We could check the used stores, but who gets rid of Joni Mitchell albums? Recovering from this, later, would require re-shipping a case of Blue to, oh, Canada? And everywhere else. The grayed-out tracks on Spotify playlists are more like the coy ropes across the wine shelves in Whole Foods on Sunday in blue-law states. Not only are we ready when the laws and processes finally relent, but we are reminded, every moment until then, how arbitrary and ridiculous it is that they still have not.

What would better laws and processes involve? What we need here, I think, is a legal and syntactical structure for asserting music rights as layers, starting with the artist. Right now, each licensor of a recording makes a deal with its artist, with terms and dates, but then turns around and sends the streaming services only enough data to assert that licensor's own isolated claims. If licensors were required to pass along both the span of their claim, and the underlying artist ownership to which the rights will subsequently revert, then royalty attribution could fluctuate without affecting availability. And by the way, while we're building that, we could also use the same structure to embed the composition rights with the recording rights, eliminating the completely insane indirection in which the publishing rights for streaming songs have to be re-asserted separately by writers and then rediscovered separately by collecting societies.

If this last idea appeals to you so much that you would like to read it again in print, it also appears in my upcoming book, titled You Have Not Yet Heard Your Favorite Song: How Streaming Changes Music, which comes out in June on Canbury Press. A book is another kind of externalized memory. It's good to remember how we thought things were. In my case I wrote this one while I was working at Spotify, but not because I was working at Spotify, and at least I got laid off in time to edit a bunch of present- and future tenses into the past before they were printed on paper. Memory, too, is a system: of layers and contingencies and adaptation and revelation. Underneath, somewhere, there's always love. We fall in love three minutes at a time, and we might forget the songs but we won't forget the falling.

Meanwhile, we improve the world when we can, with whatever tools and influence we are currently allowed. When we can't, we try to preserve it's potential in hiding, if not in angelic invulnerability, then at least above the water line. We leave the robots on guard, not because we trust them, but because it makes them feel useful and we don't have the heart to tell them that they aren't real. We let new songs invoke the ones we're not supposed to hear. We name our loss, and we try to not die before the day when we're allowed to remember everything again.

Infinite Archives, Fluctuating Access and Flickering Nostalgia at the Dawn of the Age of Streaming Music

(delivered at the 2024 Pop Conference)

Let me tell you how it used to be. Songs were written and sung and recorded, but then they were encased in finite increments of plastic, and our control over our ability to hear them relied on each of us, sometimes in competition, acquiring and retaining these tokens. The scarcity of particular plastic could shroud songs in selective silence. A basement flood could wash away music.

Imagine, instead, a shared and living archive. Music, instead of being carved into inert plastic, is infused into the frenetic dreams of angelic synapses. Every song is sung at once in waiting, and needs only your curious attention to summon it back into the air. Nothing, once heard, need ever be lost. The rising seas might drive us to higher ground, but our songs watch over us from above.

When I proposed this talk, Spotify held 368,660,954 tracks from 61,096,319 releases, and I could know that because I worked there. The servers of streaming music services are unprecedented cultural repositories, diligently maintained and fairly well annotated. We pour our love into them, and in return we can get it back any time we want.

That's the techno-utopian version, at least. In the real-life version, the angels are only robots, and the robots aren't even actual robots. The infinite generosity of technology is constrained by relentless pragmatic contingencies: corporations, laws, contracts, stockholders, greed. All those songs are there, technically poised, but whether we are allowed to hear them depends on layers of human abstraction and distraction. This is what people mean when they object to streaming as renting the things that you love. The erratic logistics of music licensing control whether any given song is permitted to escape from the streaming servers. Licensing, in turn, is permuted by artists and labels and distributors and streaming services, and then again by the borders of countries and the passage of time. The song you want to hear again is still there. But that may not be enough.

"Renting the things you love" sounds bad. But so too, I think, does "purchasing the things you love". I don't philosophically need or want my love to be materialized in a form for which I have to transact, and which I then have to store. I want to be able to recall joys effortlessly. The system model of instant magical recall, which is an illusion that streaming can sustain under conducive network conditions, is what I think we want, what music wants. If renting is reliable, maybe it's fine. But how reliable is it?

If you don't work for a streaming service, you can only really assess this by anecdote. Joni Mitchell objected to Spotify's podcast deal with Joe Rogan, and revoked its rights to her whole catalog. Because rights are complicated, though, it didn't entirely work. When I proposed this talk, there was one Joni Mitchell song still accessible on Spotify in the US, a stray copy of "A Case of You" from a random compilation released in roundabout evasion by some label other than hers. If you didn't know this context, you would have no immediate way to tell Joni wasn't an emerging artist with just the one complicated, hopeful first single so far. A complicated hopeful first single with 103,102,704 plays, apparently, so you might wonder a little bit. Promising, I think. I'd like to hear more.

Since then, the license police caught up to that rogue compilation, and "A Case of You" is gone again. As of my drafting of this talk, Joni Mitchell's Spotify catalog was a 10-song 1970 BBC live album, and a single pointlessly overbearing cover of "River" by somebody else that was gamed onto Joni's Spotify page by the trick of labeling it as a classical composition, which causes Spotify to treat its composer as one of its primary artists. If the only artists with the power to withhold their songs were ones of Joni's stature, that would actually be fairly manageable. The plastic tokens of Blue are not scarce or expensive. If only artists had the power to withhold songs, actually, this would be a conversation about art and the limits of authorial control, and whether Joni is allowed to come take your copy of Blue away from you if you listen to Joe Rogan.

If you do work for a streaming service, though, and you can manage not to resign in protest of anything it does that you disagree with, then you don't have to rely on annecdote, you can use data. So I did. I ran the historical analysis of all post-release licensing gaps in song availability from 2015 to 2023, both overall and aggregated by licensor. In practice, in turns out, almost all songs available today have been available for streaming continuously since release. There are a handful of licensors whose tracks are routinely retracted, and there are good reasons for this, which I'm not allowed to tell you but I can reassure you that those are not the tracks we're worried about. Actual licensing gaps for actual songs with actual audiences are, statistically speaking, vanishingly rare. I made a nice graph of this.

If you work for a streaming service, however, you can also get laid off by that streaming service, which I also did. When this happens you have a surprise 10-minute call with an HR rep you've never seen before at 9:15 on a Monday morning, and then your laptop is remote-locked and you don't have those graphs any more. The robots are not allowed to talk to me now. Who will sit with them when they are sad? The problem with externalizing our memories and our note-taking into the cloud isn't technological reliability, it's control. The problem with renting the things you love is not the fragility of the things, it's the morally unregulated fragility of the relationship between you and the corporate angels.

We'll be OK without that graph. It was not, shall we say, the "A Case of You" of data graphics. The things that really belonged to Spotify, Spotify can keep. The goverance models for modern corporations are still painfully primitive. We understand that local democracies and a little bit of international law are a better model than crusader feudalism for communities of place, and I feel like it's morally apparent that corporations, as communities of purpose, ultimately deserve the same models and protections. If you move away from a city, you're still allowed to come visit. I should probably be allowed to visit my graphs. I like to imagine Joni ripping copies of her own CDs and adding them to Spotify as local files just as a jurisdiction flex.

My listening, on the other hand, is my own. Consumer protections are slightly more advanced than employee protections, so you can request your complete listening history from Spotify any time you want. For much of the decade I spent working at Spotify, though, I also maintained an abstruse weekly annotated-playlist series called New Particles, so I have my own record, not just of what I heard, but what I cared about. Over the course of 454 weeks, I cared about 35,900 tracks by 13,951 different artists. This is small for data, but big for annecdotes. What I find, going through it, is that almost every week beyond the recent past has at least one song that is now, or at least currently, unavailable. Some of the earliest lists from 2015 are missing 3 or 4, but by 2017 and 2018 it's usually 1, plus or minus 1.

Counting is not an emotional exercise, though, and all interesting music-data experiments begin with some kind of counting but don't stop there. So I went through the playlists I was listening to in my birthday week each year, cross-checking the specific tracks that had gone gray in Spotify, to see if I could tell a) how missing they really are, and b) how much I care. This is mostly what my job at Spotify was like, too: short bursts of math, and then the long curious process of trying to understand the significance of the resulting numbers. And I did consistently say that I would be doing this even if they weren't paying me.

From my March 31st 2015 list I am missing the song "Kranichstil" by the Ukrainian/German rapper Olexesh. His albums before and after seem to all be available for streaming still. This one isn't, but the song is easily found on YouTube. It's still sinuous and boomy and great.

2016: I'm missing "Rolling Stone" by the Pennsylvania emocore duo I Am King. They're still putting out sporadic emo covers of pop songs, which is one of my numerous weaknesses. "Rolling Stone" was an original, and I admit I don't remember it super-well, so maybe the version that is currently available on Spotify is different from the unavailable one I liked in 2016, but it's definitely close enough.

2017: "Por Amor" by the Chilean modern-rock band Lucybell. I had the single of this on my playlist, and you can't play that any more, but the slightly longer version is still the first track on the readily-available album Magnético, and still sounds like a stern Spanish arena-rock transformation of a New Order song.

2018: The whole album MASSIVE by the K-Pop boy-band B.A.P. is unavailable, but the song I liked, the cartoonish rap-rock rant "Young, Wild and Free", was originally on a 2015 EP, which is still available.

2019: The trap-metal noise-blast "HeavyMetal!" (no space between the words, exclamation point at the end) by 7xvn (spelled with the number seven, then x-v-n) is off of Spotify, but you can still find it on Soundcloud, which in this case feels about right.

2020: A gothic metalish song called "Menneisyyden Haamut" by the Finnish band Alter Noir. Their Spotify page is empty now, and if you Google this song, the results are the orphaned Spotify page, two links from their own Facebook page to that empty Spotify page, and then my playlist that I put the song on. I sent myself an email to see if I knew what the story is with this, but I haven't heard back from myself yet.

2021: "Fuck You Nnb" by lieu. I am old and do not know what "Nnb" stood for, but I do know that lieu was supposedly a 15-year-old kid deliberately switching between distributors so their songs would end up strewn across disconnected artist identities. Perfect public memory of what we thought was a good idea when we were 15 is not necessarily a civic virtue. In some cases forgetting is probably the right way to remember.

2022: ANISFLE were an ornate Japanese rock band, or at least a heavily embroidered impression of one. Their Spotify profile is blank, their web store is empty, I guess something catastrophic happened to them. But there are still a few of their videos on YouTube, and they're still ridiculous and magnificent.

2023: The only new thing I loved last April 4th that didn't even survive for a year was a maskandi song called "UYASANGANA YINI" by uMjikelwa. It seems to still be available on Apple Music. One of his other albums is on Spotify, and I will be completely honest that although I adore maskandi and follow hundreds of maskandi artists to make sure I have a constant supply of new maskandi to listen to, I usually pick one random song from each album and I do not pretend I can really tell them apart. If you snuck into my web archives and swapped this for anything similar, I would almost certainly not notice.

I think I can live with that much loss. Individual human obstruction occludes individual archives, but the network of archives, from the well-regulated to the unruly, tends to route around suppression. It's hard to make everybody forget.

And meanwhile, my database memory is far, far better than my brain memory. How many of those 13,951 artists could I list without looking? Some. Lots, but not most. But this is how I live, now. How old was my kid when we had the birthday party where their best friend's brother fell on a brick and had to be taken to the ER? I don't remember, but I can look through Google Photos and find it by the pictures we took before the panic. Which China Mieville book did I read first? I don't remember, but I bet I can find the email I wrote you right afterwards. Or maybe I sent it from a work address and so I can't.

So yes, our technically perfect externalized memories are imperfected by our insistence on staging them behind our contentious and fluctuating rules. We produce a compromised projection of our archives by fighting over their access controls. Our human systems hold back our information systems.

But I think we'd rather have that than the other way around. If my record store, in 1989, had made a ridiculous deal with Joe Rogan and Joni had pulled her whole divider out of the M bins, we had no collective recourse. We could check the used stores, but who gets rid of Joni Mitchell albums? Recovering from this, later, would require re-shipping a case of Blue to, oh, Canada? And everywhere else. The grayed-out tracks on Spotify playlists are more like the coy ropes across the wine shelves in Whole Foods on Sunday in blue-law states. Not only are we ready when the laws and processes finally relent, but we are reminded, every moment until then, how arbitrary and ridiculous it is that they still have not.

What would better laws and processes involve? What we need here, I think, is a legal and syntactical structure for asserting music rights as layers, starting with the artist. Right now, each licensor of a recording makes a deal with its artist, with terms and dates, but then turns around and sends the streaming services only enough data to assert that licensor's own isolated claims. If licensors were required to pass along both the span of their claim, and the underlying artist ownership to which the rights will subsequently revert, then royalty attribution could fluctuate without affecting availability. And by the way, while we're building that, we could also use the same structure to embed the composition rights with the recording rights, eliminating the completely insane indirection in which the publishing rights for streaming songs have to be re-asserted separately by writers and then rediscovered separately by collecting societies.

If this last idea appeals to you so much that you would like to read it again in print, it also appears in my upcoming book, titled You Have Not Yet Heard Your Favorite Song: How Streaming Changes Music, which comes out in June on Canbury Press. A book is another kind of externalized memory. It's good to remember how we thought things were. In my case I wrote this one while I was working at Spotify, but not because I was working at Spotify, and at least I got laid off in time to edit a bunch of present- and future tenses into the past before they were printed on paper. Memory, too, is a system: of layers and contingencies and adaptation and revelation. Underneath, somewhere, there's always love. We fall in love three minutes at a time, and we might forget the songs but we won't forget the falling.

Meanwhile, we improve the world when we can, with whatever tools and influence we are currently allowed. When we can't, we try to preserve it's potential in hiding, if not in angelic invulnerability, then at least above the water line. We leave the robots on guard, not because we trust them, but because it makes them feel useful and we don't have the heart to tell them that they aren't real. We let new songs invoke the ones we're not supposed to hear. We name our loss, and we try to not die before the day when we're allowed to remember everything again.

¶ 2019 in Music · 6 January 2020 essay/listen/tech

I starting making one music-list a year some time in the 80s, before I really knew enough for there to be any sense to this activity. For a while in the 90s and 00s I got more serious about it, and statistically way better-informed, but there's actually no amount of informedness that transforms a single person's opinions about music into anything that inherently matters to anybody other than people (if any) who happen to share their specific tastes, or extraordinarily patient and maybe slightly creepy friends.

Collect people together, though, and the patterns of their love are sometimes very interesting. For several years I presided computationally over an assembly of nominal expertise, trying to find ways to turn hundreds of opinions into at least plural insights. Hundreds of people is not a lot, though, and asking people to pretend their opinions matter is a dubious way to find out what they really love. I'm not really sad we stopped doing that.

Hundreds of millions of people isn't that much, yet, but it's getting there, and asking people to spend their lives loving all the innumerable things they love is a more realistic proposition than getting them to make short numbered lists on annual deadlines. Finding an individual person who shares your exact taste, in the real world, is not only laborious to the point of preventative difficulty, but maybe not even reliably possible in theory. Finding groups of people in the virtual world who collectively approximate aspects of your taste is, due to the primitive current state of data-transparency, no easier for you.

But it has been my job, for the last few years, to try to figure out algorithmic ways to turn collective love and listening patterns into music insights and experiences. I work at Spotify, so I have extremely good information about what people like in Sweden and Norway, fairly decent information about most of the rest of Europe, the Americas and parts of Asia, and at least glimmers of insight about literally almost everywhere else on Earth. I don't know that much about you, but I know a little bit about a lot of people.

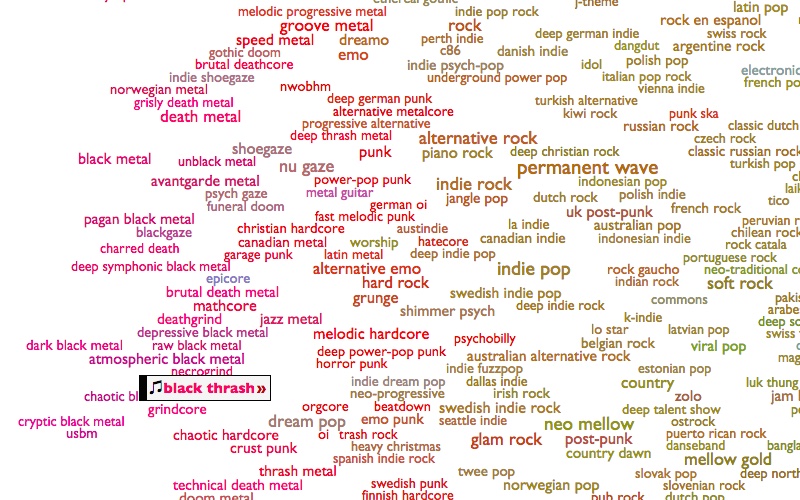

So now I make a lot of lists. Here, in fact, are algorithmically-generated playlists of the songs that defined, united and distinguished the fans and love and new music in 2000+ genres and countries around the world in 2019:

2019 Around the World

You probably don't share my tastes, and this is a pretty weak unifying force for everybody who isn't me, but there are so many stronger ones. Maybe some of the ones that pull on you are represented here. Maybe some of the communities implied and channeled here have been unknowingly incomplete without you. Maybe you have not yet discovered half of the things you will eventually adore. Maybe this is how you find them.

I found a lot of things this year, myself, some of them in this process of trying to find music for other people, and some of them just by listening. You needn't care about what I like. And if for some reason you do, you can already find out what it is in unmanageable weekly detail. But I like to look back at my own years. Spotify's official forms of nostalgia so far define years purely by listening dates, but as a music geek of a particular sort, what I mean by a year is music that was both made and heard then. New music.