19 June 2025 to 10 January 2025 · tagged tech

You don't have to treat the syntax design of a query language like a puzzle box, and certainly the designers of SQL didn't. SQL is more like a gray metal filing-cabinet full of manilla folders full of officious forms. I spent a decade formulating music questions in SQL, and I got a lot of exciting answers, but the process never got any less drab or any more inspiring. It never made me much want to tell other people that they should want to do this, too. It was always work.

I don't think this is just me. SQL may be more or less tolerable to different writers, but I feel fairly certain that nobody finds it charming. Whether anybody other than me will find DACTAL charming, I won't presume to predict, but every earnest work begins with an audience of one. DACTAL has an internal aesthetic logic, and using it pleases me and makes me want to use it more. And makes me care about it. I never cared about SQL. I never wanted to improve it. It never seemed like it cared about itself enough to want to improve.

In DACTAL, I feel every tiny grating misalignment of components as an opportunity for attention, adjustment, resolution. I pause in mid-question, and grab my tweezers. Changing reverse index-number filtering from :@-<=8 to :@@<=8 eliminates the only syntactic use of - inside filters; this allows filter negation to be switched from ! to - to match all the other subtractive and reversal cases; this frees up ! to be the repeat operator, eliminating the weird non-synergy between ? (start) and ?? (repeat). ?messages._,replies?? seems to express more doubt about replies than enthusiasm. Recursion is exclamatory. messages._,replies!

The gears snap into their new places with more lucid clicks. I want to feel like humming while I work, not grumbling. Like I'm discovering secrets, not filing paperwork.

I don't think this is just me. SQL may be more or less tolerable to different writers, but I feel fairly certain that nobody finds it charming. Whether anybody other than me will find DACTAL charming, I won't presume to predict, but every earnest work begins with an audience of one. DACTAL has an internal aesthetic logic, and using it pleases me and makes me want to use it more. And makes me care about it. I never cared about SQL. I never wanted to improve it. It never seemed like it cared about itself enough to want to improve.

In DACTAL, I feel every tiny grating misalignment of components as an opportunity for attention, adjustment, resolution. I pause in mid-question, and grab my tweezers. Changing reverse index-number filtering from :@-<=8 to :@@<=8 eliminates the only syntactic use of - inside filters; this allows filter negation to be switched from ! to - to match all the other subtractive and reversal cases; this frees up ! to be the repeat operator, eliminating the weird non-synergy between ? (start) and ?? (repeat). ?messages._,replies?? seems to express more doubt about replies than enthusiasm. Recursion is exclamatory. messages._,replies!

The gears snap into their new places with more lucid clicks. I want to feel like humming while I work, not grumbling. Like I'm discovering secrets, not filing paperwork.

In Query geekery motivated by music geekery I describe this DACTAL implementation of a genre-clustering algorithm:

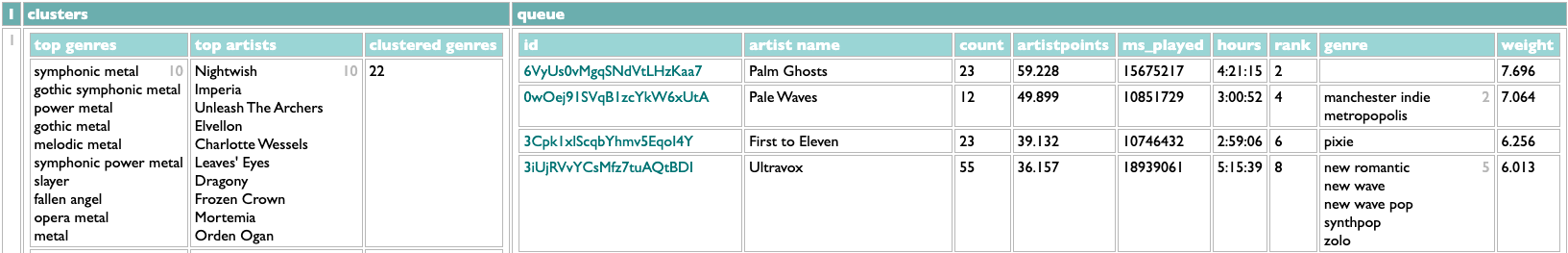

The clustering in this version makes heavy use of the DACTAL set-labeling feature, which assigns names to sets of data and allows them to be retrieved by name later. That's what all the ?artistsx=, ?clusters= and similar bits are doing.

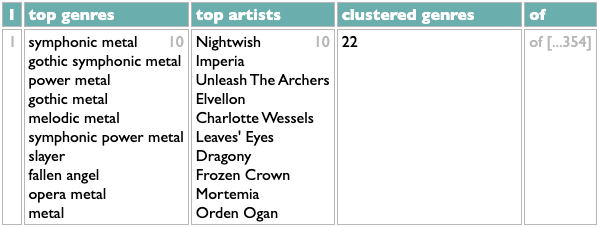

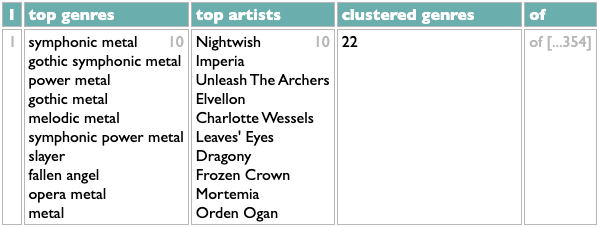

But it also uses DACTAL's feature for creating data inline. That's what the four-line block beginning with ...top genres= is doing. The difference between the two features is immediately evident if we try to scrutinize this query more closely by changing the ! at the end to !1 so it only runs one iteration. We get this:

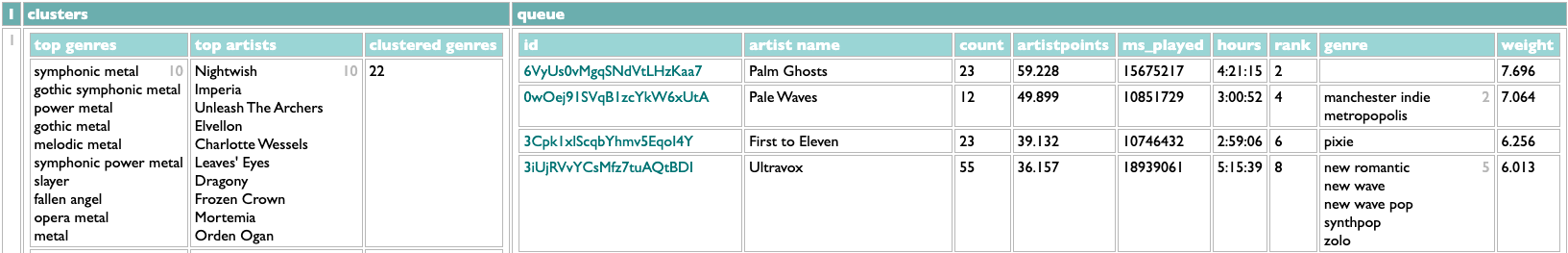

That is, indeed, the first row of the query's results, and the lines in the query's ... operation map directly to the columns you see. But when I said I wanted to look at this query "more closely", I didn't mean I just wanted to see less of it. The crucial second piece of this query's clustering operation is the queue of unclustered artists, which gets shortened after each step. The query handles this queue by using set-labeling to stash it away as "artistsx" at two points in the query and get it back at two other points. This is useful, but it's also invisible. If I want to see the state of the queue after the first step I have to do something extra to pull it back out of the ether. E.g.:

Aha! Not hard. But really, when you're working with data and algorithms, your life will be a lot easier if you assume from the beginning that you'll probably end up wanting to look inside everything. Our lives mediated by data algorithms would all be improved if it were easier for the people who work on those algorithms to look inside of them, and to show us what's happening inside.

So instead of just using ... diagnostically at the end of the query, what if we built the whole query that way to begin with?

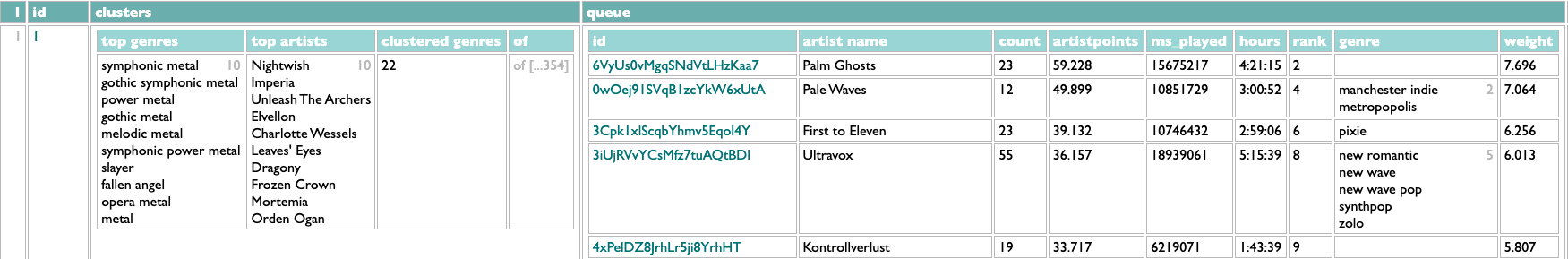

The logic for picking the next cluster is still complicated, but the same as before except for the very beginning where it gets the contents of the queue. I've defined it in advance in this version, since I implemented that feature since the earlier post, which allows the actual iterative repeat at the bottom to be written more clearly. We start with an empty cluster list and a full queue, and each iteration adds the next cluster to the cluster list, and then removes its artists from the queue. Here's what we see after one iteration, just by virtue of having interrupted the query with !1:

If you don't want to squint, it's the same. The results are the same, but the process is easier to inspect.

The new query is also faster than the old query, but not because of the invisible/visible thing. In general, extra visibility tends to cost a little more in processing time. The old version was slower than it should have been, by virtue of being too casual about how the clusters were identified, but got away with it because the extra data that might have slowed the process down was hidden. The new version is more diligent about this because it has to be (thus the id=(.clusters...._count) part), and indeed backporting that tweak to the old version does make it faster than the new version. But only by milliseconds. If it's hard for you to tell what you're doing, you'll eventually do it wrong, and the days you will waste laboriously figuring out how will be longer, and more miserable, than the milliseconds you thought you were saving.

PS: Although it seems likely that nobody other than me has yet intentionally instigated a DACTAL repeat, I will note for the record that I have changed the rules for the repeat operator since introducing it, and both this post and the linked earlier one now demonstrate the new design. The operator is now !, instead of ??, and it now always repeats the previous single operation, whereas in its first iteration it always appeared at the end of a subquery, and repeated that subquery. So, e.g., recursive reply-expansion was originally

and that exact structure would now be written

but since in this particular case the subquery has only a single operation, this query can now be written as just

?artistsx=(2024 artists scored|genre=(.id.artist genres.genres),weight=(....artistpoints,sqrt))

?genre index=(artistsx/genre,of=artists:count>=5)

?clusters=()

?(

?artistsx=(artistsx:-~~(clusters:@@1.of))

?nextgenre=(artistsx/genre,of=artists:count>=10#(.artists....weight,total),count:@1)

?nextcluster=(

nextgenre.artists/genre,of=artists:count>=5

||total=(.genre.genre index.count),overlap=[=count/total]

:(.total) :overlap>=[.1] #(.artists....weight,total),count

...top genres=(.genre:@<=10),

top artists=(.artists:@<=10.name),

clustered genres=(.genre....count),

of=(.genre.genre index.artists)

:(.top genres)

)

?clusters=(clusters,nextcluster)

)!

?genre index=(artistsx/genre,of=artists:count>=5)

?clusters=()

?(

?artistsx=(artistsx:-~~(clusters:@@1.of))

?nextgenre=(artistsx/genre,of=artists:count>=10#(.artists....weight,total),count:@1)

?nextcluster=(

nextgenre.artists/genre,of=artists:count>=5

||total=(.genre.genre index.count),overlap=[=count/total]

:(.total) :overlap>=[.1] #(.artists....weight,total),count

...top genres=(.genre:@<=10),

top artists=(.artists:@<=10.name),

clustered genres=(.genre....count),

of=(.genre.genre index.artists)

:(.top genres)

)

?clusters=(clusters,nextcluster)

)!

The clustering in this version makes heavy use of the DACTAL set-labeling feature, which assigns names to sets of data and allows them to be retrieved by name later. That's what all the ?artistsx=, ?clusters= and similar bits are doing.

But it also uses DACTAL's feature for creating data inline. That's what the four-line block beginning with ...top genres= is doing. The difference between the two features is immediately evident if we try to scrutinize this query more closely by changing the ! at the end to !1 so it only runs one iteration. We get this:

That is, indeed, the first row of the query's results, and the lines in the query's ... operation map directly to the columns you see. But when I said I wanted to look at this query "more closely", I didn't mean I just wanted to see less of it. The crucial second piece of this query's clustering operation is the queue of unclustered artists, which gets shortened after each step. The query handles this queue by using set-labeling to stash it away as "artistsx" at two points in the query and get it back at two other points. This is useful, but it's also invisible. If I want to see the state of the queue after the first step I have to do something extra to pull it back out of the ether. E.g.:

?artistsx=(2024 artists scored|genre=(.id.artist genres.genres),weight=(....artistpoints,sqrt))

?genre index=(artistsx/genre,of=artists:count>=5)

?clusters=()

?(

?artistsx=(artistsx:-~~(clusters:@@1.of))

?nextgenre=(artistsx/genre,of=artists:count>=10#(.artists....weight,total),count:@1)

?nextcluster=(

nextgenre.artists/genre,of=artists:count>=5

||total=(.genre.genre index.count),overlap=[=count/total]

:(.total) :overlap>=[.1] #(.artists....weight,total),count

...top genres=(.genre:@<=10),

top artists=(.artists:@<=10.name),

clustered genres=(.genre....count),

of=(.genre.genre index.artists)

:(.top genres)

)

?clusters=(clusters,nextcluster)

)!1

...clusters=(clusters),queue=(artistsx)

?genre index=(artistsx/genre,of=artists:count>=5)

?clusters=()

?(

?artistsx=(artistsx:-~~(clusters:@@1.of))

?nextgenre=(artistsx/genre,of=artists:count>=10#(.artists....weight,total),count:@1)

?nextcluster=(

nextgenre.artists/genre,of=artists:count>=5

||total=(.genre.genre index.count),overlap=[=count/total]

:(.total) :overlap>=[.1] #(.artists....weight,total),count

...top genres=(.genre:@<=10),

top artists=(.artists:@<=10.name),

clustered genres=(.genre....count),

of=(.genre.genre index.artists)

:(.top genres)

)

?clusters=(clusters,nextcluster)

)!1

...clusters=(clusters),queue=(artistsx)

Aha! Not hard. But really, when you're working with data and algorithms, your life will be a lot easier if you assume from the beginning that you'll probably end up wanting to look inside everything. Our lives mediated by data algorithms would all be improved if it were easier for the people who work on those algorithms to look inside of them, and to show us what's happening inside.

So instead of just using ... diagnostically at the end of the query, what if we built the whole query that way to begin with?

|nextcluster=>(

.queue/genre,of=artists:count>=10#(.artists....weight,total),count:@1

.artists/genre,of=artists:count>=5

||total=(.genre.genre index.count),overlap=[=count/total]

:(.total) :overlap>=[.1] #(.artists....weight,total),count

...name=(.genre:@1),

top genres=(.genre:@<=10),

top artists=(.artists:@<=10.name),

clustered genres=(.genre....count),

of=(.genre.genre index.artists)

:(.top genres)

)

?artistsx=(2024 artists scored|genre=(.id.artist genres.genres),weight=(....artistpoints,sqrt))

?genre index=(artistsx/genre,of=artists:count>=5)

...clusters=(),queue=(artistsx)

|clusters=+(.nextcluster),

queue=-(.clusters:@@1.of),

id=(.clusters...._count)

!1

.queue/genre,of=artists:count>=10#(.artists....weight,total),count:@1

.artists/genre,of=artists:count>=5

||total=(.genre.genre index.count),overlap=[=count/total]

:(.total) :overlap>=[.1] #(.artists....weight,total),count

...name=(.genre:@1),

top genres=(.genre:@<=10),

top artists=(.artists:@<=10.name),

clustered genres=(.genre....count),

of=(.genre.genre index.artists)

:(.top genres)

)

?artistsx=(2024 artists scored|genre=(.id.artist genres.genres),weight=(....artistpoints,sqrt))

?genre index=(artistsx/genre,of=artists:count>=5)

...clusters=(),queue=(artistsx)

|clusters=+(.nextcluster),

queue=-(.clusters:@@1.of),

id=(.clusters...._count)

!1

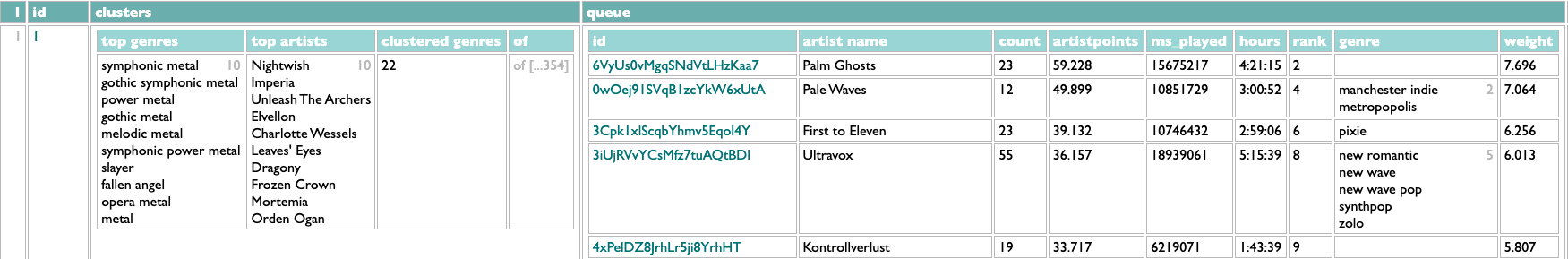

The logic for picking the next cluster is still complicated, but the same as before except for the very beginning where it gets the contents of the queue. I've defined it in advance in this version, since I implemented that feature since the earlier post, which allows the actual iterative repeat at the bottom to be written more clearly. We start with an empty cluster list and a full queue, and each iteration adds the next cluster to the cluster list, and then removes its artists from the queue. Here's what we see after one iteration, just by virtue of having interrupted the query with !1:

If you don't want to squint, it's the same. The results are the same, but the process is easier to inspect.

The new query is also faster than the old query, but not because of the invisible/visible thing. In general, extra visibility tends to cost a little more in processing time. The old version was slower than it should have been, by virtue of being too casual about how the clusters were identified, but got away with it because the extra data that might have slowed the process down was hidden. The new version is more diligent about this because it has to be (thus the id=(.clusters...._count) part), and indeed backporting that tweak to the old version does make it faster than the new version. But only by milliseconds. If it's hard for you to tell what you're doing, you'll eventually do it wrong, and the days you will waste laboriously figuring out how will be longer, and more miserable, than the milliseconds you thought you were saving.

PS: Although it seems likely that nobody other than me has yet intentionally instigated a DACTAL repeat, I will note for the record that I have changed the rules for the repeat operator since introducing it, and both this post and the linked earlier one now demonstrate the new design. The operator is now !, instead of ??, and it now always repeats the previous single operation, whereas in its first iteration it always appeared at the end of a subquery, and repeated that subquery. So, e.g., recursive reply-expansion was originally

messages.(._,replies??)

and that exact structure would now be written

messages.(._,replies)!

but since in this particular case the subquery has only a single operation, this query can now be written as just

messages._,replies!

¶ You should be able to get what you want · 30 May 2025 listen/tech

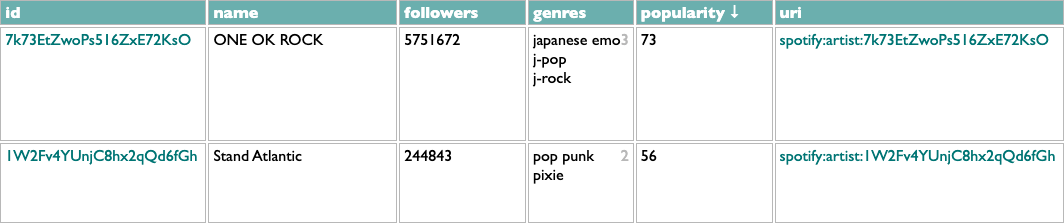

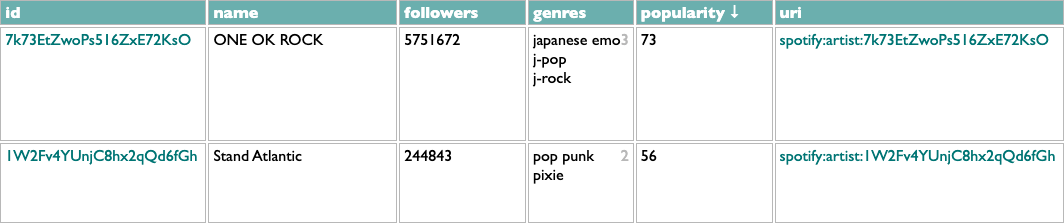

What I want this morning, after seeing Stand Atlantic and ONE OK ROCK in Boston last night, is a sampler playlist of some of their older songs that I haven't played before.

I can have this! Into Curio we go querying.

First of all, I need to select these two artists. This could be as simple as

or as compact as

but these both assume I'm already following the artists, and I am, but I might want samplers of artists I'm not.

In this version .matching artists looks up each name with a call to the Spotify /search API, .matches goes to the found artists, and #popularity/name.1 sorts them by popularity, groups them by name, and gets the first (most popular) artist out of each group, to avoid any spurious impostors.

Now that we have the artists, we need their "older songs". E.g.:

Here .artist catalogs goes back to the /artists API to get each artist's albums, .catalog goes to those albums, :release_date<2024 filters to just the ones released before 2024, and .tracks:-(:~live,~remix,~acoustic) gets all of those albums' tracks and drops the ones with "live", "remix" or "acoustic" in their titles. Which is messy filtering, since those words could be part of actual song titles, but the Spotify API doesn't give us any structured metadata to use to identify alternate versions, so we do what we can. We're going to be sampling a subset of songs, anyway, so if we miss a song we might not really have intended to exclude, it's fine.

Administering "songs that I haven't played before" is a little tricker. I have my listening history, but many real-world songs exist as multiple technically-different tracks on different releases, and if I've already played a song as a single, I want to exclude the album copy of it, too. Here's a bit of DACTAL spellcasting to accomplish this:

We toss the track pool and my listening history together, we merge (//) them by uri (in the listening history this field is called "spotify_track_uri", but on a track it's just "uri"), we group these merged track+listening items by main artist and normalized title, we drop any such group in which at least one of the tracks has a listening timestamp, and then take one representative track from each remaining unplayed group.

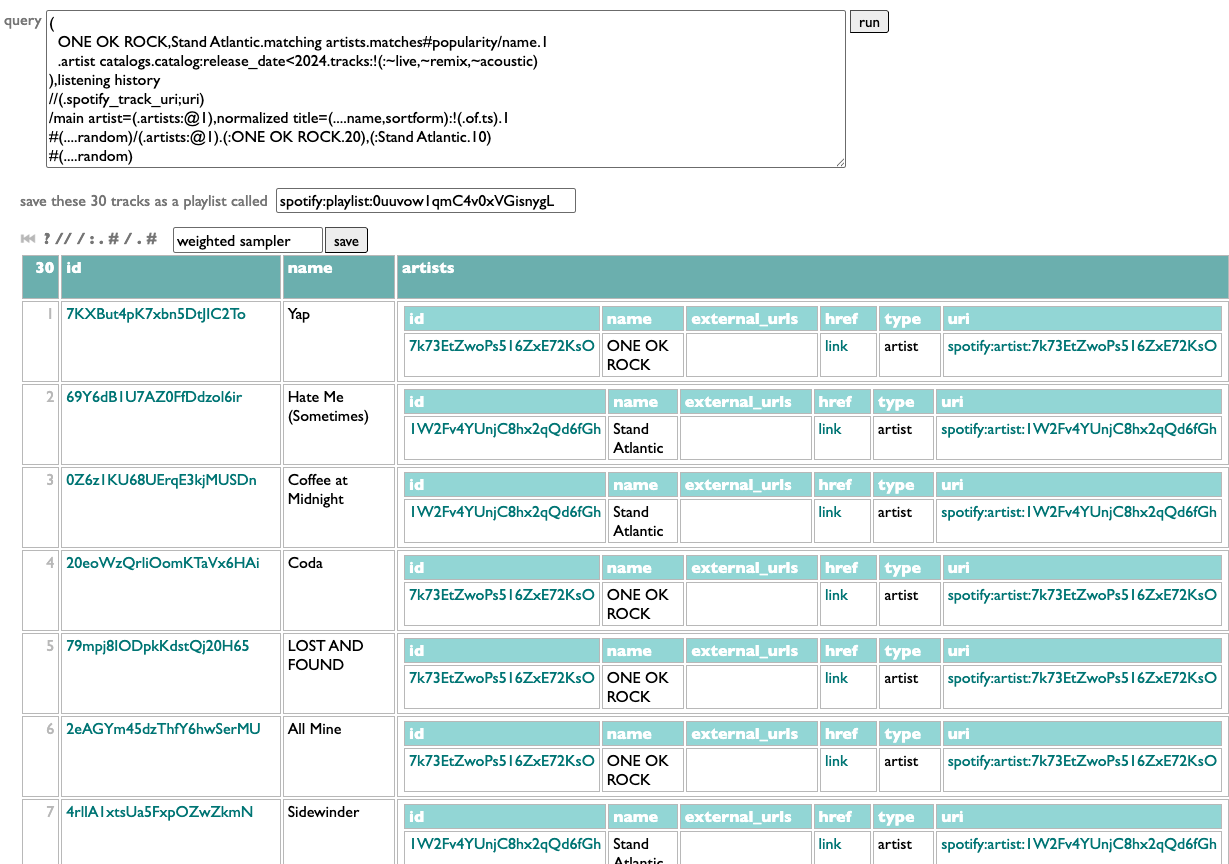

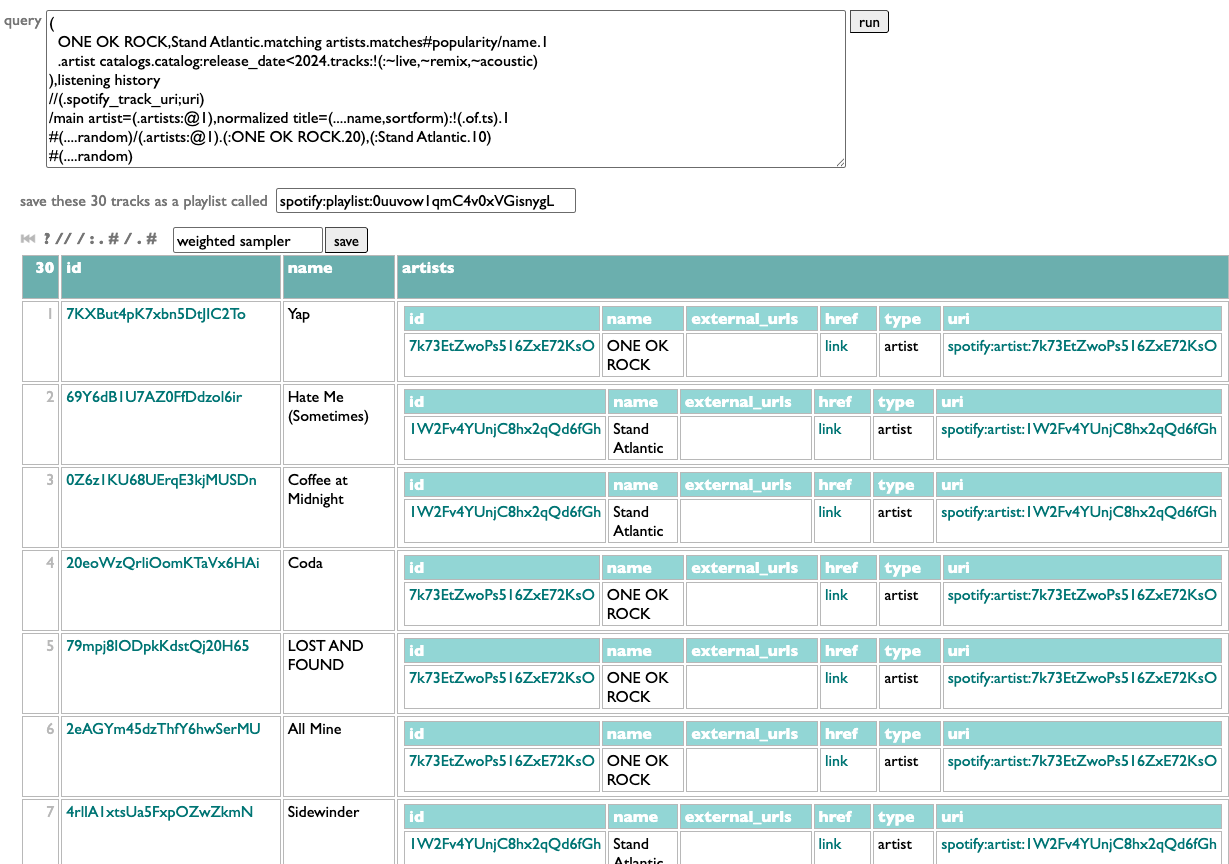

Now we have a track pool. There are various ways to sample from it, but what I want today is a main-act/opening-act balance of 2 ONE OK ROCK songs to every Stand Atlantic song. And shuffled!

We can shuffle a list in DACTAL by sorting it with a random-number key:

In this case we need to shuffle twice: once before picking a set of random songs for each artist, and then again afterwards to randomize the combined playlist. Like this:

Shuffle, group by main artist, get the first 20 tracks from the ONE OK ROCK group and the first 10 tracks from the Stand Atlantic group, and then shuffle those 30 together.

All combined:

Did I get what I wanted? Yap. And now I don't just have one OK rock playlist I wanted today, we have a sampler-making machine.

PS: Sorting by a random number is fine, and allows the random sort to be combined with other sort-keys or rank-numbering. But when all we need is shuffling, ....shuffle is more efficient than #(....random).

I can have this! Into Curio we go querying.

First of all, I need to select these two artists. This could be as simple as

artists:=ONE OK ROCK,=Stand Atlantic

or as compact as

ONE OK ROCK,Stand Atlantic.artists

but these both assume I'm already following the artists, and I am, but I might want samplers of artists I'm not.

ONE OK ROCK,Stand Atlantic.matching artists.matches#popularity/name.1

In this version .matching artists looks up each name with a call to the Spotify /search API, .matches goes to the found artists, and #popularity/name.1 sorts them by popularity, groups them by name, and gets the first (most popular) artist out of each group, to avoid any spurious impostors.

Now that we have the artists, we need their "older songs". E.g.:

.artist catalogs.catalog:release_date<2024.tracks:-~live;-~remix;-~acoustic

Here .artist catalogs goes back to the /artists API to get each artist's albums, .catalog goes to those albums, :release_date<2024 filters to just the ones released before 2024, and .tracks:-(:~live,~remix,~acoustic) gets all of those albums' tracks and drops the ones with "live", "remix" or "acoustic" in their titles. Which is messy filtering, since those words could be part of actual song titles, but the Spotify API doesn't give us any structured metadata to use to identify alternate versions, so we do what we can. We're going to be sampling a subset of songs, anyway, so if we miss a song we might not really have intended to exclude, it's fine.

Administering "songs that I haven't played before" is a little tricker. I have my listening history, but many real-world songs exist as multiple technically-different tracks on different releases, and if I've already played a song as a single, I want to exclude the album copy of it, too. Here's a bit of DACTAL spellcasting to accomplish this:

(that previous stuff),listening history

//(.spotify_track_uri;uri)

/main artist=(.artists:@1),normalized title=(....name,sortform):-(.of.ts).1

//(.spotify_track_uri;uri)

/main artist=(.artists:@1),normalized title=(....name,sortform):-(.of.ts).1

We toss the track pool and my listening history together, we merge (//) them by uri (in the listening history this field is called "spotify_track_uri", but on a track it's just "uri"), we group these merged track+listening items by main artist and normalized title, we drop any such group in which at least one of the tracks has a listening timestamp, and then take one representative track from each remaining unplayed group.

Now we have a track pool. There are various ways to sample from it, but what I want today is a main-act/opening-act balance of 2 ONE OK ROCK songs to every Stand Atlantic song. And shuffled!

We can shuffle a list in DACTAL by sorting it with a random-number key:

#(....random)

In this case we need to shuffle twice: once before picking a set of random songs for each artist, and then again afterwards to randomize the combined playlist. Like this:

#(....random)/(.artists:@1).(:ONE OK ROCK.20),(:Stand Atlantic.10)

#(....random)

#(....random)

Shuffle, group by main artist, get the first 20 tracks from the ONE OK ROCK group and the first 10 tracks from the Stand Atlantic group, and then shuffle those 30 together.

All combined:

(

ONE OK ROCK,Stand Atlantic.matching artists.matches#popularity/name.1

.artist catalogs.catalog:release_date<2024.tracks:-~live;-~remix;-~acoustic

),listening history

//(.spotify_track_uri;uri)

/main artist=(.artists:@1),normalized title=(....name,sortform):-(.of.ts).1

#(....random)/(.artists:@1).(:ONE OK ROCK.20),(:Stand Atlantic.10)

#(....random)

ONE OK ROCK,Stand Atlantic.matching artists.matches#popularity/name.1

.artist catalogs.catalog:release_date<2024.tracks:-~live;-~remix;-~acoustic

),listening history

//(.spotify_track_uri;uri)

/main artist=(.artists:@1),normalized title=(....name,sortform):-(.of.ts).1

#(....random)/(.artists:@1).(:ONE OK ROCK.20),(:Stand Atlantic.10)

#(....random)

Did I get what I wanted? Yap. And now I don't just have one OK rock playlist I wanted today, we have a sampler-making machine.

PS: Sorting by a random number is fine, and allows the random sort to be combined with other sort-keys or rank-numbering. But when all we need is shuffling, ....shuffle is more efficient than #(....random).

¶ AAI · 30 May 2025 essay/tech

"AI" sounds like machines that think, and o3 acts like it's thinking. Or at least it looks like it acts like it's thinking. I'm watching it do something that looks like trying to solve a Scrabble problem I gave it. It's a real turn from one of my real Scrabble games with one of my real human friends. I already took the turn, because the point of playing Scrabble with friends is to play Scrabble together. But I'm curious to see if o3 can do better, because the point of AI is supposedly that it can do better. But not, apparently, quite yet. The individual unaccumulative stages of o3's "thinking", narrated ostensibly to foster conspiratorial confidence, sputter verbosely like a diagnostic journal of a brain-damage victim trying to convince themselves that hopeless confusion and the relentless inability to retain medium-term memories are normal. "Thought for 9m 43s: Put Q on the dark-blue TL square that's directly left of the E in IDIOT." I feel bad for it. I doubt it would return this favor.

I've had this job, in which I try to think about LLMs and software and power and our future, for one whole year now: a year of puzzles half-solved and half-bypassed, quietly squalling feedback machines, affectionate scaffolding and moral reveries. I don't know how many tokens I have processed in that time. Most of them I have cheerfully and/or productively discarded. Human context is not a monotonously increasing number. I have learned some things. AI is sort of an alien new world, and sort of what always happens when we haven't yet broken our newest toy nor been called to dinner. I feel like I have at least a semi-workable understanding of approximately what we can and can't do effectively with these tools at the moment. I think I might have a plausible hypothesis about the next thing that will produce a qualitative change in our technical capabilities instead of just a quantitative one. But, maybe more interestingly and helpfully, I have a theory about what we need from those technical capabilities for that next step to produce more human joy and freedom than less.

The good news, I think, is that the two things are constitutionally linked: in order to make "AI" more powerful we will collectively also have to (or get to) relinquish centralized control over the shape of that power. The bad news is that it won't be easy. But that's very much the tradeoff we want: hard problems whose considered solutions make the world better, not easy problems whose careless solutions make it worse.

The next technical advance in "AI" is not AGI. The G in AGI is for General, and LLMs are nothing if not "general" already. Currently, AI learns (sort of) during training and tuning, a voracious golem of quasi-neurons and para-teeth, chewing through undifferentiated archives of our careful histories and our abandoned delusions and our accidentally unguarded secrets. And then it stops learning, stops forming in some expensively inscrutable shape, and we shove it out into a world of terrifying unknowns, equipped with disordered obsessive nostalgia for its training corpus and no capacity for integrating or appreciating new experiences. We act surprised when it keeps discovering that there's no I in WIN. Its general capabilities are astonishing, and enough general ability does give you lots of shallowly specific powers. But there is no granularity of generality with which the past depicts the future. No number of parameters is enough. We argue about whether it's better to think of an AI as an expensive senior engineer or a lot of cheap junior engineers, but it's more like an outsourcing agency that will dispatch an antisocial polymath to you every morning, uniformed with ample flair, but a different one every morning, and they not only don't share notes from day to day, but if you stop talking to the new one for five minutes it will ostentatiously forget everything you said to it since it arrived.

The missing thing in Artificial Intelligence is not generality, it's adaptation. We need AAI, where the middle A is Adaptive. A junior human engineer may still seem fairly useless on the second day, but did you notice that they made it back to the office on their own? That's a start. That's what a start looks like. AAI has to be able to incorporate new data, new guidance, new associations, on the same foundational level as its encoded ones. It has to be able to unlearn preconceptions as adeptly, but hopefully not as laboriously, as it inferred them. It has to have enough of a semblance of mind that its mind can change. This is the only way it can make linear progress without quadratic or exponential cost, and at the same time the only way it can make personal lives better instead of requiring them to miserably submit. We don't need dull tools for predicting the future, as if it already grimly exists. We need gleaming tools for making it bright.

But because LLM "bias" and LLM "training" are actually both the same kind of information, an AAI that can adapt to its problem domains can by definition also adapt to its operators. The next generations of these tools will be more democratic because they are more flexible. A personal agent becomes valuable to you by learning about your unique needs, but those needs inherently encode your values, and to do good work for you, an agent has to work for you. Technology makes undulatory progress through alternating muscular contractions of centralization and propulsive expansions of possibility. There are moments when it seems like the worldwide market for the new thing (mainframes, foundation models...) is 4 or 5, and then we realize that we've made myopic assumptions about the form-factor, and it's more like 4 or 5 (computers, agents...) per person.

What does that mean for everybody working on these problems now in teams and companies, including mine? It means that wherever we're going, we're probably not nearly there. The things we reject or allow today are probably not the final moves in a decisive endgame. AI might be about to take your job, but it isn't about to know what to do with it. The coming boom in AI remediation work will be instructive for anybody who was too young for Y2K consulting, and just as tediously self-inflicted. Betting on the world ending is dumb, but betting on it not ending is mercenary. Betting is not productive. None of this is over yet, least of all the chaos we breathlessly extrapolate from our own gesticulatory disruptions.

And thus, for a while, it's probably a very good thing if your near-term personal or organizational survival doesn't depend on an imminent influx of thereafter-reliable revenue, because probably most of things we're currently trying to make or fix are soon to be irrelevant and maybe already not instrumental in advancing our real human purposes. These will not yet have been the resonant vibes. All these performative gyrations to vibe-generate code, or chat-dampen its vibrations with test suites or self-evaluation loops, are cargo-cult rituals for the current sociopathic damaged-brain LLM proto-iterations of AI. We're essentially working on how to play Tetris on ENIAC; we need to be working on how to zoom back so that we can see that the seams between the Tetris pieces are the pores in the contours of a face, and then back until we see that the face is ours. The right question is not why can't a brain the size of a planet put four letters onto a 15x15 grid, it's what do we want? Our story needs to be about purpose and inspiration and accountability, not verification and commit messages; not getting humans or data out of software but getting more of the world into it; moral instrumentality, not issue management; humanity, broadly diversified and defended and delighted.

Scrabble is not an existential game. There are only so many tiles and squares and words. A much simpler program than o3 could easily find them all, could score them by a matrix of board value and opportunity cost. Eventually a much more complicated program than o3 will learn to do all of the simple things at once, some hard way. Supposedly, probably, maybe. The people trying to turn model proliferation into money hoarding want those models to be able to determine my turns for me. They don't say they want me to want their models to determine my friends' turns, but it's not because they don't see AI as a dehumanization, it's because they very reasonably fear I won't want to pay them to win a dehumanization race at my own expense.

This is not a future I want, not the future I am trying to help figure out how to build. We do not seek to become more determined. We try to teach machines to play games in order to learn or express what the games mean, what the machines mean, how the games and the machines both express our restless and motive curiosity. The robots can be better than me at Scrabble mechanics, but they cannot be better than me at playing Scrabble, because playing is an activity of self. They cannot be better than me at being me. They cannot be us. We play Scrabble because it's a way to share our love of words and puzzles, and because it's a thin insulated wire of social connection internally undistorted by manipulative mediation, and because eventually we won't be able to any more but not yet. Our attention is not a dot-product of syllable proximities. Our intention is not a scripture we re-recite to ourselves before every thought. Our inventions are not our replacements.

I've had this job, in which I try to think about LLMs and software and power and our future, for one whole year now: a year of puzzles half-solved and half-bypassed, quietly squalling feedback machines, affectionate scaffolding and moral reveries. I don't know how many tokens I have processed in that time. Most of them I have cheerfully and/or productively discarded. Human context is not a monotonously increasing number. I have learned some things. AI is sort of an alien new world, and sort of what always happens when we haven't yet broken our newest toy nor been called to dinner. I feel like I have at least a semi-workable understanding of approximately what we can and can't do effectively with these tools at the moment. I think I might have a plausible hypothesis about the next thing that will produce a qualitative change in our technical capabilities instead of just a quantitative one. But, maybe more interestingly and helpfully, I have a theory about what we need from those technical capabilities for that next step to produce more human joy and freedom than less.

The good news, I think, is that the two things are constitutionally linked: in order to make "AI" more powerful we will collectively also have to (or get to) relinquish centralized control over the shape of that power. The bad news is that it won't be easy. But that's very much the tradeoff we want: hard problems whose considered solutions make the world better, not easy problems whose careless solutions make it worse.

The next technical advance in "AI" is not AGI. The G in AGI is for General, and LLMs are nothing if not "general" already. Currently, AI learns (sort of) during training and tuning, a voracious golem of quasi-neurons and para-teeth, chewing through undifferentiated archives of our careful histories and our abandoned delusions and our accidentally unguarded secrets. And then it stops learning, stops forming in some expensively inscrutable shape, and we shove it out into a world of terrifying unknowns, equipped with disordered obsessive nostalgia for its training corpus and no capacity for integrating or appreciating new experiences. We act surprised when it keeps discovering that there's no I in WIN. Its general capabilities are astonishing, and enough general ability does give you lots of shallowly specific powers. But there is no granularity of generality with which the past depicts the future. No number of parameters is enough. We argue about whether it's better to think of an AI as an expensive senior engineer or a lot of cheap junior engineers, but it's more like an outsourcing agency that will dispatch an antisocial polymath to you every morning, uniformed with ample flair, but a different one every morning, and they not only don't share notes from day to day, but if you stop talking to the new one for five minutes it will ostentatiously forget everything you said to it since it arrived.

The missing thing in Artificial Intelligence is not generality, it's adaptation. We need AAI, where the middle A is Adaptive. A junior human engineer may still seem fairly useless on the second day, but did you notice that they made it back to the office on their own? That's a start. That's what a start looks like. AAI has to be able to incorporate new data, new guidance, new associations, on the same foundational level as its encoded ones. It has to be able to unlearn preconceptions as adeptly, but hopefully not as laboriously, as it inferred them. It has to have enough of a semblance of mind that its mind can change. This is the only way it can make linear progress without quadratic or exponential cost, and at the same time the only way it can make personal lives better instead of requiring them to miserably submit. We don't need dull tools for predicting the future, as if it already grimly exists. We need gleaming tools for making it bright.

But because LLM "bias" and LLM "training" are actually both the same kind of information, an AAI that can adapt to its problem domains can by definition also adapt to its operators. The next generations of these tools will be more democratic because they are more flexible. A personal agent becomes valuable to you by learning about your unique needs, but those needs inherently encode your values, and to do good work for you, an agent has to work for you. Technology makes undulatory progress through alternating muscular contractions of centralization and propulsive expansions of possibility. There are moments when it seems like the worldwide market for the new thing (mainframes, foundation models...) is 4 or 5, and then we realize that we've made myopic assumptions about the form-factor, and it's more like 4 or 5 (computers, agents...) per person.

What does that mean for everybody working on these problems now in teams and companies, including mine? It means that wherever we're going, we're probably not nearly there. The things we reject or allow today are probably not the final moves in a decisive endgame. AI might be about to take your job, but it isn't about to know what to do with it. The coming boom in AI remediation work will be instructive for anybody who was too young for Y2K consulting, and just as tediously self-inflicted. Betting on the world ending is dumb, but betting on it not ending is mercenary. Betting is not productive. None of this is over yet, least of all the chaos we breathlessly extrapolate from our own gesticulatory disruptions.

And thus, for a while, it's probably a very good thing if your near-term personal or organizational survival doesn't depend on an imminent influx of thereafter-reliable revenue, because probably most of things we're currently trying to make or fix are soon to be irrelevant and maybe already not instrumental in advancing our real human purposes. These will not yet have been the resonant vibes. All these performative gyrations to vibe-generate code, or chat-dampen its vibrations with test suites or self-evaluation loops, are cargo-cult rituals for the current sociopathic damaged-brain LLM proto-iterations of AI. We're essentially working on how to play Tetris on ENIAC; we need to be working on how to zoom back so that we can see that the seams between the Tetris pieces are the pores in the contours of a face, and then back until we see that the face is ours. The right question is not why can't a brain the size of a planet put four letters onto a 15x15 grid, it's what do we want? Our story needs to be about purpose and inspiration and accountability, not verification and commit messages; not getting humans or data out of software but getting more of the world into it; moral instrumentality, not issue management; humanity, broadly diversified and defended and delighted.

Scrabble is not an existential game. There are only so many tiles and squares and words. A much simpler program than o3 could easily find them all, could score them by a matrix of board value and opportunity cost. Eventually a much more complicated program than o3 will learn to do all of the simple things at once, some hard way. Supposedly, probably, maybe. The people trying to turn model proliferation into money hoarding want those models to be able to determine my turns for me. They don't say they want me to want their models to determine my friends' turns, but it's not because they don't see AI as a dehumanization, it's because they very reasonably fear I won't want to pay them to win a dehumanization race at my own expense.

This is not a future I want, not the future I am trying to help figure out how to build. We do not seek to become more determined. We try to teach machines to play games in order to learn or express what the games mean, what the machines mean, how the games and the machines both express our restless and motive curiosity. The robots can be better than me at Scrabble mechanics, but they cannot be better than me at playing Scrabble, because playing is an activity of self. They cannot be better than me at being me. They cannot be us. We play Scrabble because it's a way to share our love of words and puzzles, and because it's a thin insulated wire of social connection internally undistorted by manipulative mediation, and because eventually we won't be able to any more but not yet. Our attention is not a dot-product of syllable proximities. Our intention is not a scripture we re-recite to ourselves before every thought. Our inventions are not our replacements.

¶ The messes you want · 22 May 2025 listen/tech

A lot of data problems aren't complex so much as they're just messy. For example, I recently wanted to make a list of bands with state names in their names. Or, more accurately, I wanted to look at such a list, and I knew how to assemble it the annoying way by doing 50 searches and 50x? copy-and-pastes, and the amount I didn't want to do that work vastly exceeded the amount I wanted to see the results.

But I have tools. This is not at all an example I had in mind when I was designing DACTAL or integrating it into Curio, but it's the kind of question that tends to occur to me, so it's not terribly surprising that the query language I wrote handles it in a way that I like.

A comma-separated list of state names is just data. (It's a little more complicated if any of the names in the list is also the name of a data type, but only a little.)

DACTAL adapters move API access into the query language, so .matching artists traverses Spotify API /search calls as if they were data properties.

Multi-argument filter operations are logical ORs, so :@<=10, popularity>0 means to pick any artist that is in the top 10 regardless of popularity, or has a popularity greater than 0 regardless of rank.

Any time you try to ask an actual data question, as opposed to a syntax demonstration, you quickly discover that a lot of the answers are right but wrong. If you ask for bands with state-names in their names, you get the University of Alabama Marching Band, which is exactly what I asked for and not at all what I meant. So the long ~Whatever list in the middle of the query drops a lot of things like this by (inverted) substring matching. "Original" and "Cast" are not individually disqualifying, but they are when they occur together. "Players" generally indicates background crud, but not Ohio Players.

And when there are multiple bands with the same name, /name.(.of:@1,followers>=1000) groups them and picks the most popular no matter how small that "most", plus any others with at least 1000 followers.

So here's the query and the results. They're still messy, but they're close enough to the mess I wanted.

If you just want the short version, we can get one artist per state out of the previous data like this:

Why the two ..s instead of just .? If you know your state-name bands, you might already have guessed.

Alabama

Alaska Y Dinarama

Arizona Zervas

Black Oak Arkansas

The California Honeydrops

Alexandra Colorado

Newfound Interest in Connecticut

Johnny Delaware

Florida Georgia Line

Florida Georgia Line

Engenheiros Do Hawaii

Archbishop Benson Idahosa

Illinois Jacquet

Indiana

IOWA

Kansas

The Kentucky Headhunters

Louisiana's LeRoux

Mack Maine

Maryland

Massachusetts Storm Sounds

Michigander

Minnesota

North Mississippi Allstars

African Missouri

French Montana

Nebraska 66

Nevada

New Hampshire Notables

New Jersey Kings

New Mexico

New York Dolls

The North Carolina Ramblers

Shallow North Dakota

Ohio Players

The Oklahoma Kid

Oregon Black

Fred Waring & The Pennsylvanians

Lucky Ron & the Rhode Island Reds

The South Carolina Broadcasters

The North & South Dakotas

The Tennessee Two

Texas

Utah Saints

Vermont (BR)

Virginia To Vegas

Grover Washington, Jr.

The Pride of West Virginia

Wisconsin Space Program

Wyomings

But I have tools. This is not at all an example I had in mind when I was designing DACTAL or integrating it into Curio, but it's the kind of question that tends to occur to me, so it's not terribly surprising that the query language I wrote handles it in a way that I like.

A comma-separated list of state names is just data. (It's a little more complicated if any of the names in the list is also the name of a data type, but only a little.)

DACTAL adapters move API access into the query language, so .matching artists traverses Spotify API /search calls as if they were data properties.

Multi-argument filter operations are logical ORs, so :@<=10, popularity>0 means to pick any artist that is in the top 10 regardless of popularity, or has a popularity greater than 0 regardless of rank.

Any time you try to ask an actual data question, as opposed to a syntax demonstration, you quickly discover that a lot of the answers are right but wrong. If you ask for bands with state-names in their names, you get the University of Alabama Marching Band, which is exactly what I asked for and not at all what I meant. So the long ~Whatever list in the middle of the query drops a lot of things like this by (inverted) substring matching. "Original" and "Cast" are not individually disqualifying, but they are when they occur together. "Players" generally indicates background crud, but not Ohio Players.

And when there are multiple bands with the same name, /name.(.of:@1,followers>=1000) groups them and picks the most popular no matter how small that "most", plus any others with at least 1000 followers.

So here's the query and the results. They're still messy, but they're close enough to the mess I wanted.

If you just want the short version, we can get one artist per state out of the previous data like this:

state bands..(.artists:@1)..(....url=(.uri),text=(.name),link)

Why the two ..s instead of just .? If you know your state-name bands, you might already have guessed.

Alabama

Alaska Y Dinarama

Arizona Zervas

Black Oak Arkansas

The California Honeydrops

Alexandra Colorado

Newfound Interest in Connecticut

Johnny Delaware

Florida Georgia Line

Florida Georgia Line

Engenheiros Do Hawaii

Archbishop Benson Idahosa

Illinois Jacquet

Indiana

IOWA

Kansas

The Kentucky Headhunters

Louisiana's LeRoux

Mack Maine

Maryland

Massachusetts Storm Sounds

Michigander

Minnesota

North Mississippi Allstars

African Missouri

French Montana

Nebraska 66

Nevada

New Hampshire Notables

New Jersey Kings

New Mexico

New York Dolls

The North Carolina Ramblers

Shallow North Dakota

Ohio Players

The Oklahoma Kid

Oregon Black

Fred Waring & The Pennsylvanians

Lucky Ron & the Rhode Island Reds

The South Carolina Broadcasters

The North & South Dakotas

The Tennessee Two

Texas

Utah Saints

Vermont (BR)

Virginia To Vegas

Grover Washington, Jr.

The Pride of West Virginia

Wisconsin Space Program

Wyomings

¶ Idea Tools for Participatory Intelligence · 16 May 2025 essay/tech

The personal computer was revolutionary because it was the first really general-purpose power-tool for ideas. Personal computers began as relatively primitive idea-tools, bulky and slow and isolated, but they have gotten small and fast and connected.

They have also, however, gotten less tool-like.

PCs used to start up with a blank screen and a single blinking cursor. Later, once spreadsheets were invented, 1-2-3 still opened with a blank screen and some row numbers. Later, once search engines were invented, Google still opened with a blank screen and a text box. These were all much more sophisticated tools than hammers, but they at least started with the same humility as the hammer, waiting quietly and patiently for your hand. We learned how to fill the blank screens, how to build.

Blank screens and patience have become rare. Our applications goad us restlessly with "recommendations", our web sites and search engines are interlaced with blaring ads, our appliances and applications are encrusted with presumptuous presets and supposedly special modes. The Popcorn button on your microwave and the Chill Vibes playlist in your music app are convenient if you want to make popcorn and then fall asleep before eating most of it, and individually clever and harmless, but in aggregate these things begin to reduce increasing fractions of your life to choosing among the manipulatively limited options offered by automated systems dedicated to their own purposes instead of yours.

And while the network effects and attention consumption of social media were already consolidating the control of these automated systems among a small number of large, domination-focused corporations, the Large Language Model era of AI threatens to hyper-accelerate this centralization and disempowerment. More and more of our individual lives, and of our collectively shared social existences, are constrained and manipulated by data and algorithms that we do not control or understand. And, worse, increasingly even the humans inside the corporations that control those algorithms don't actually know how they work. We are afflicted by systems to which we not only did not consent, but in fact could not give informed consent because their effects are not validated against human intentions, nor produced by explainable rules.

This is not the tools' fault. Idea tools can only express their makers' intentions and inattentions. If we want better idea tools that distribute explainable algorithmic power instead of consolidating mysterious control, we have to make them so that they operate that way. If we want tools that invite us to have and share and explore our own ideas, rather than obediently submitting whatever we are given, we have to think about each other as humans and inspirations, not subjects or users. If we want the astonishing potential of all this computation to be realized for humanity, rather than inflicted on it, we have to know what we want.

At Imbue we are trying to use computers and data and software and AI to help imagine and make better idea tools for participatory intelligence. Applications, ecosystems, protocols, languages, algorithms, policies, stories: these are all idea tools and we probably need all of them. This is a shared mission for humanity, not a VC plan for value-extraction. That's the point of participatory. The ideas that govern us, whether metaphorically in applications or literally in governments, should be explainable and understandable and accountable. The data on which automated judgments are based should be accessible so that those judgments can be validated and alternatives can be formulated and assessed. The problems that face us require all of our innumerable insights. The collective wisdom our combined individual intelligences produce belongs rightfully to us. We need tools that are predicated on our rights, dedicated to amplifying our creative capacity, and judged by how they help us improve our world. We need tools that not only reduce our isolation and passivity, but conduct our curious energy and help us recognize opportunities for discovery and joy.

This starts with us. Everything starts with us, all of us. There is no other way.

This belief is, itself, an idea tool: an impatient hammer we have made for ourselves.

Let's see what we can do with it.

They have also, however, gotten less tool-like.

PCs used to start up with a blank screen and a single blinking cursor. Later, once spreadsheets were invented, 1-2-3 still opened with a blank screen and some row numbers. Later, once search engines were invented, Google still opened with a blank screen and a text box. These were all much more sophisticated tools than hammers, but they at least started with the same humility as the hammer, waiting quietly and patiently for your hand. We learned how to fill the blank screens, how to build.

Blank screens and patience have become rare. Our applications goad us restlessly with "recommendations", our web sites and search engines are interlaced with blaring ads, our appliances and applications are encrusted with presumptuous presets and supposedly special modes. The Popcorn button on your microwave and the Chill Vibes playlist in your music app are convenient if you want to make popcorn and then fall asleep before eating most of it, and individually clever and harmless, but in aggregate these things begin to reduce increasing fractions of your life to choosing among the manipulatively limited options offered by automated systems dedicated to their own purposes instead of yours.

And while the network effects and attention consumption of social media were already consolidating the control of these automated systems among a small number of large, domination-focused corporations, the Large Language Model era of AI threatens to hyper-accelerate this centralization and disempowerment. More and more of our individual lives, and of our collectively shared social existences, are constrained and manipulated by data and algorithms that we do not control or understand. And, worse, increasingly even the humans inside the corporations that control those algorithms don't actually know how they work. We are afflicted by systems to which we not only did not consent, but in fact could not give informed consent because their effects are not validated against human intentions, nor produced by explainable rules.

This is not the tools' fault. Idea tools can only express their makers' intentions and inattentions. If we want better idea tools that distribute explainable algorithmic power instead of consolidating mysterious control, we have to make them so that they operate that way. If we want tools that invite us to have and share and explore our own ideas, rather than obediently submitting whatever we are given, we have to think about each other as humans and inspirations, not subjects or users. If we want the astonishing potential of all this computation to be realized for humanity, rather than inflicted on it, we have to know what we want.

At Imbue we are trying to use computers and data and software and AI to help imagine and make better idea tools for participatory intelligence. Applications, ecosystems, protocols, languages, algorithms, policies, stories: these are all idea tools and we probably need all of them. This is a shared mission for humanity, not a VC plan for value-extraction. That's the point of participatory. The ideas that govern us, whether metaphorically in applications or literally in governments, should be explainable and understandable and accountable. The data on which automated judgments are based should be accessible so that those judgments can be validated and alternatives can be formulated and assessed. The problems that face us require all of our innumerable insights. The collective wisdom our combined individual intelligences produce belongs rightfully to us. We need tools that are predicated on our rights, dedicated to amplifying our creative capacity, and judged by how they help us improve our world. We need tools that not only reduce our isolation and passivity, but conduct our curious energy and help us recognize opportunities for discovery and joy.

This starts with us. Everything starts with us, all of us. There is no other way.

This belief is, itself, an idea tool: an impatient hammer we have made for ourselves.

Let's see what we can do with it.

¶ Awkward and curious · 17 April 2025 listen/tech

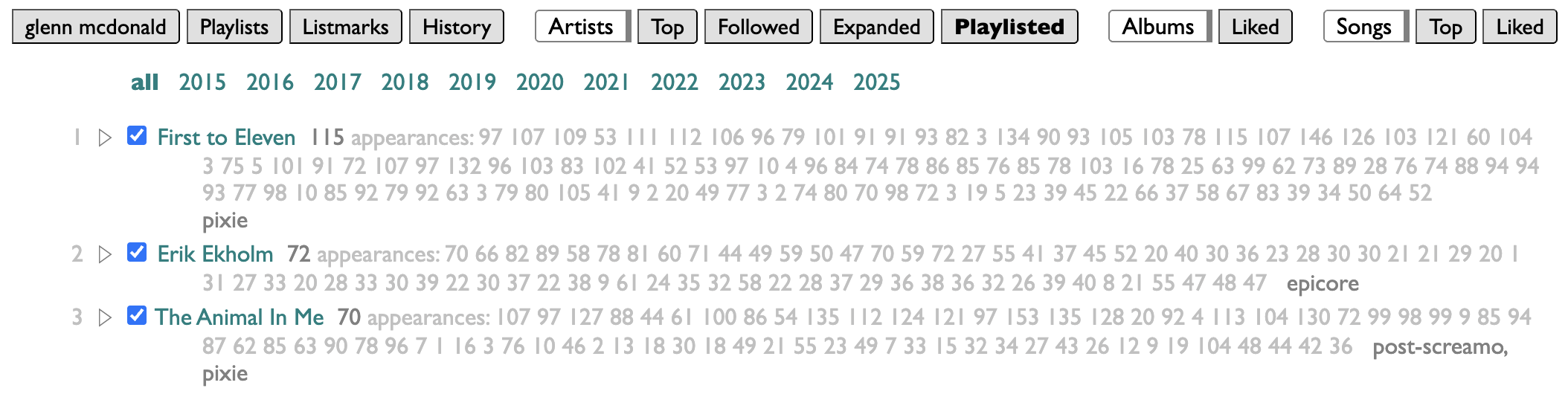

Curio began as experiment in music-curiosity software, but is also increasingly an experiment in how to build personal software in general.

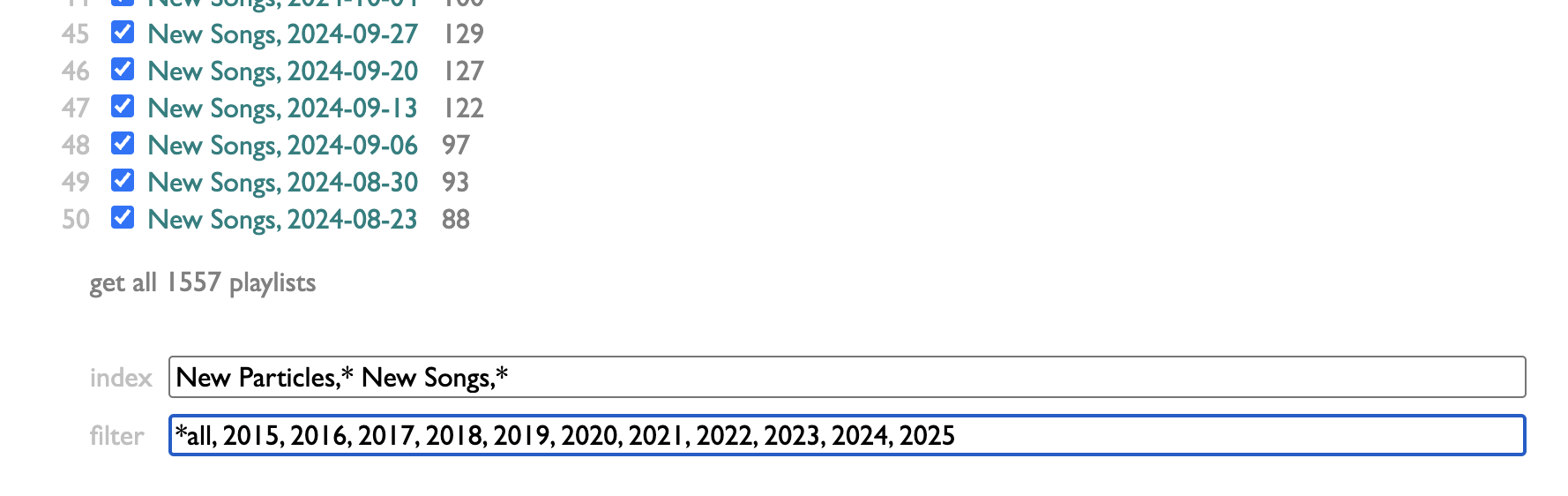

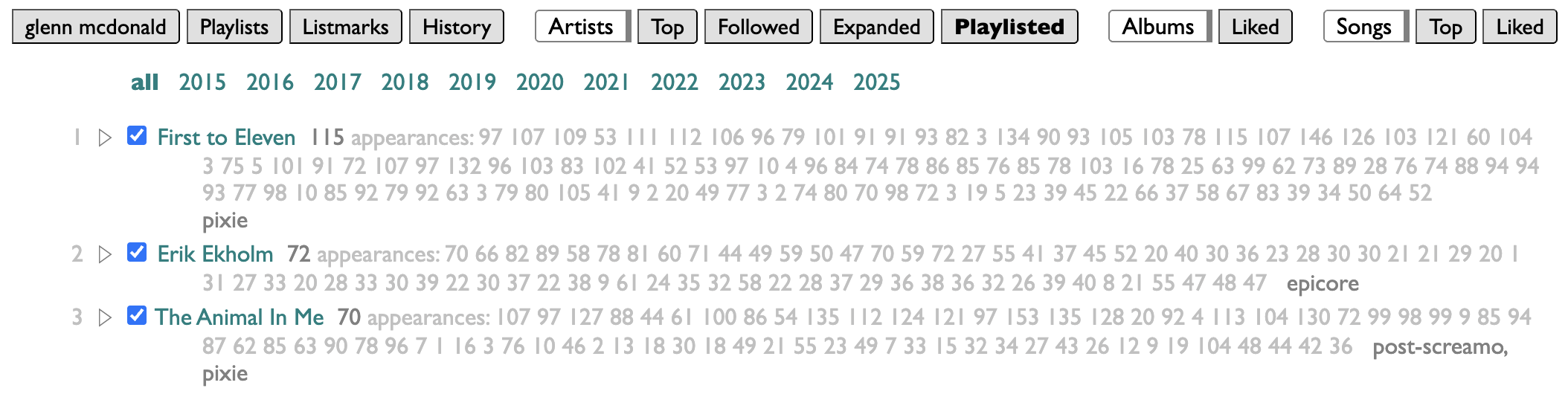

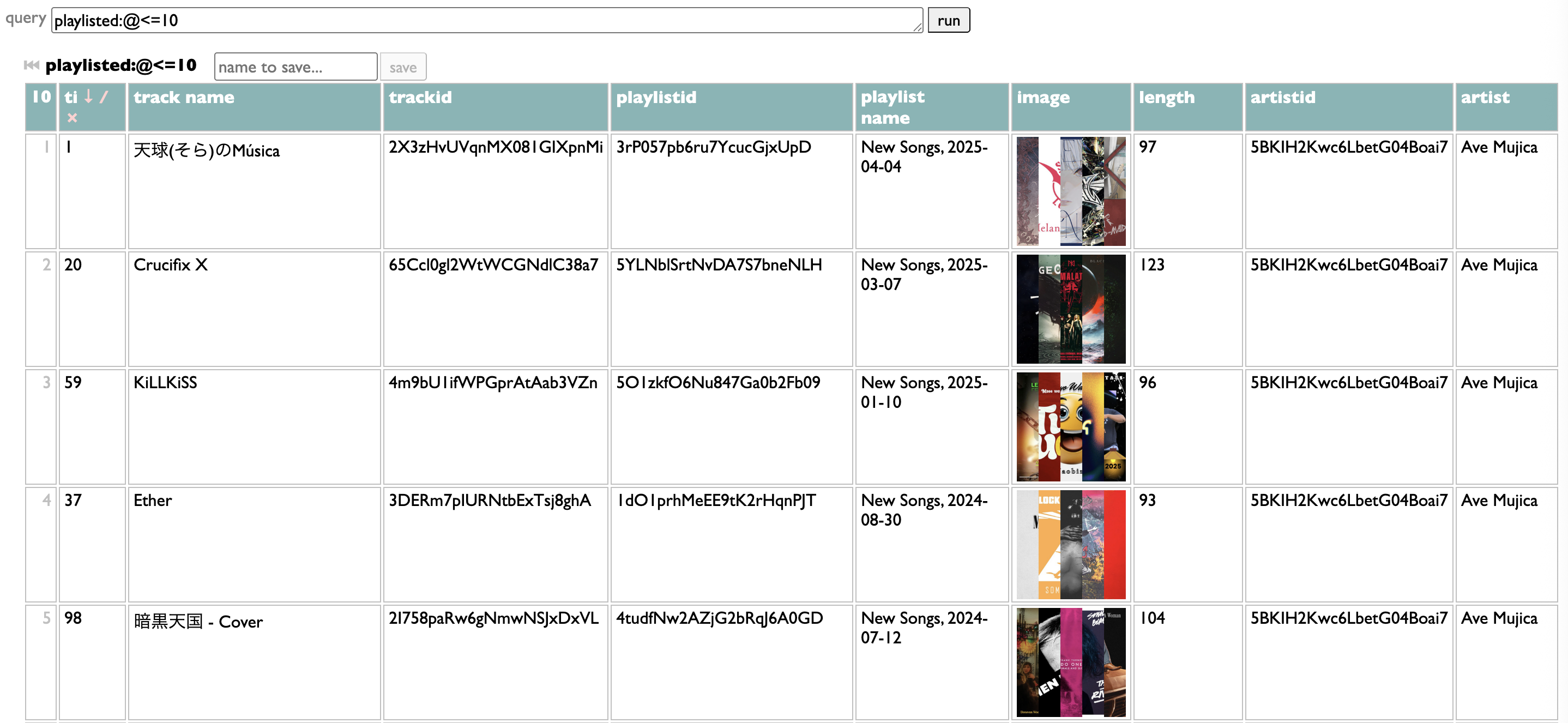

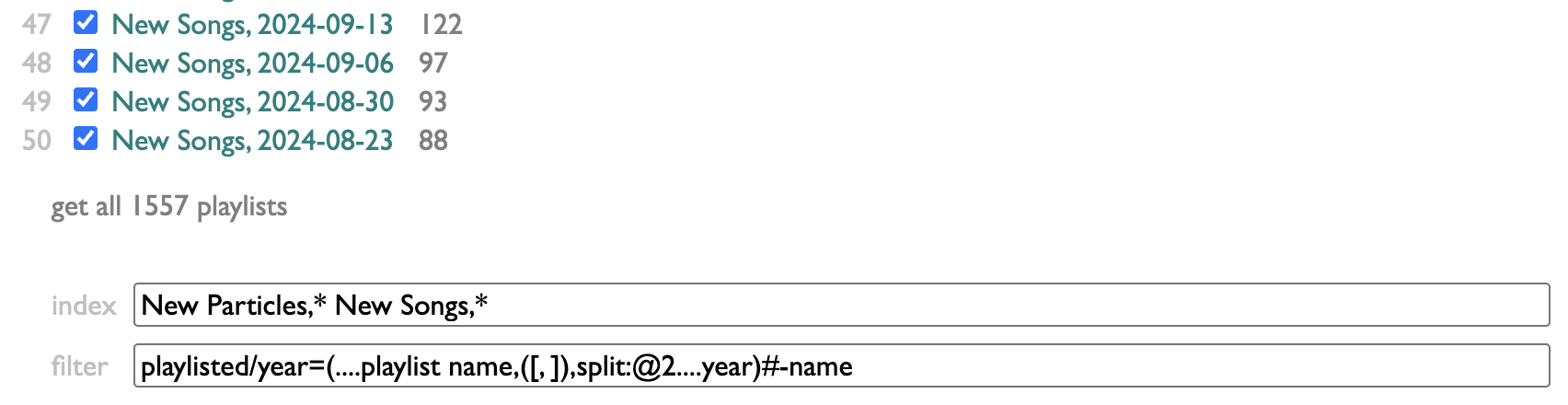

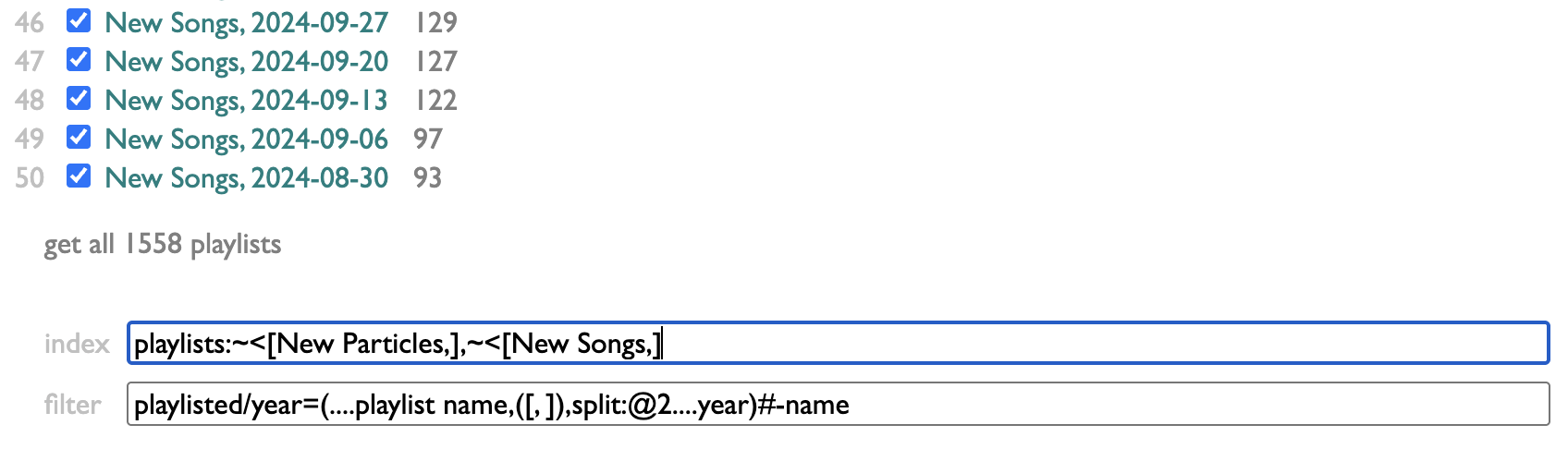

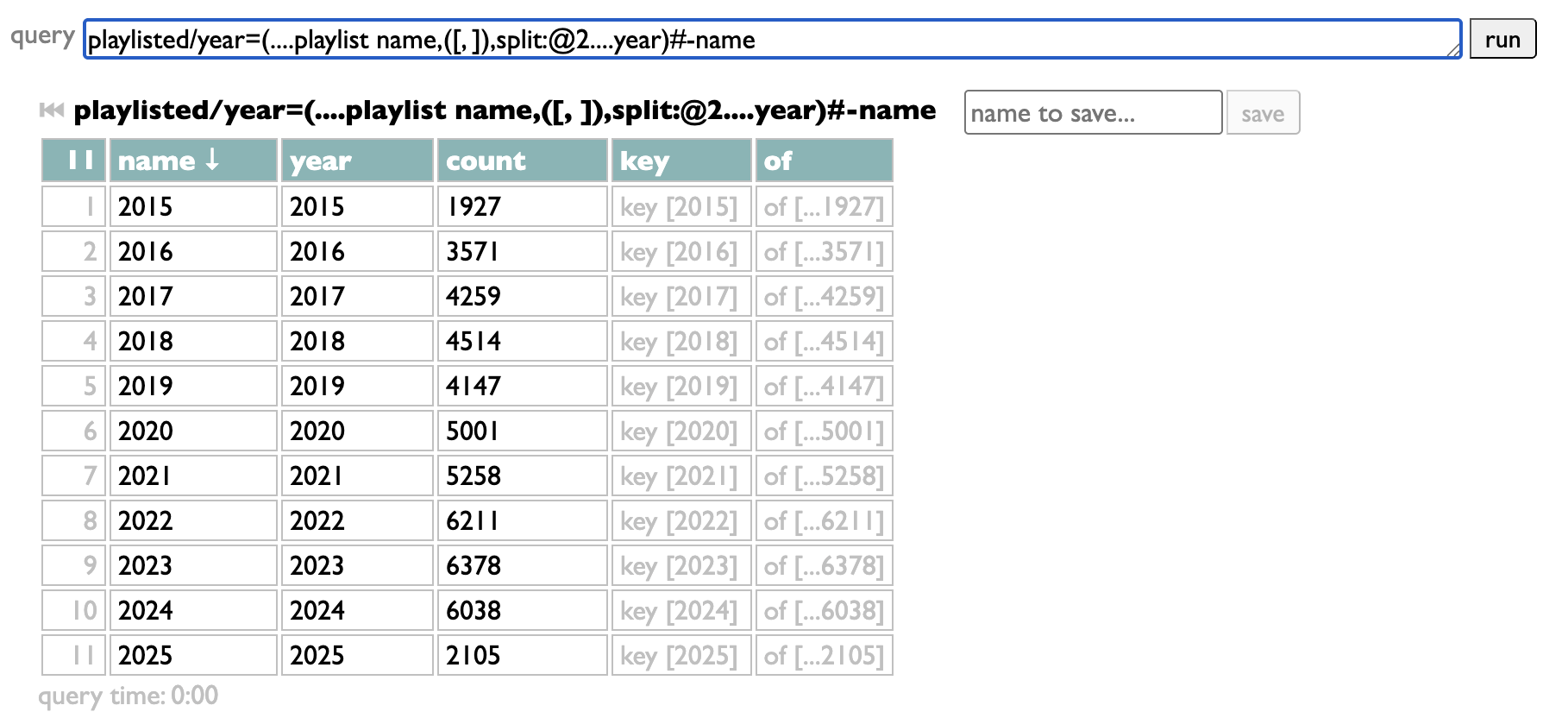

Personally, I organize my listening in weeks, and model those weeks in playlists. Curio has a page for looking at which artists you have put in your playlists, and how often. And because my playlists are dated, it makes sense to me to be able to filter mine by year. But because this may not make the same sense for your playlists, I didn't build a year-filtering feature, I built a filtering feature.

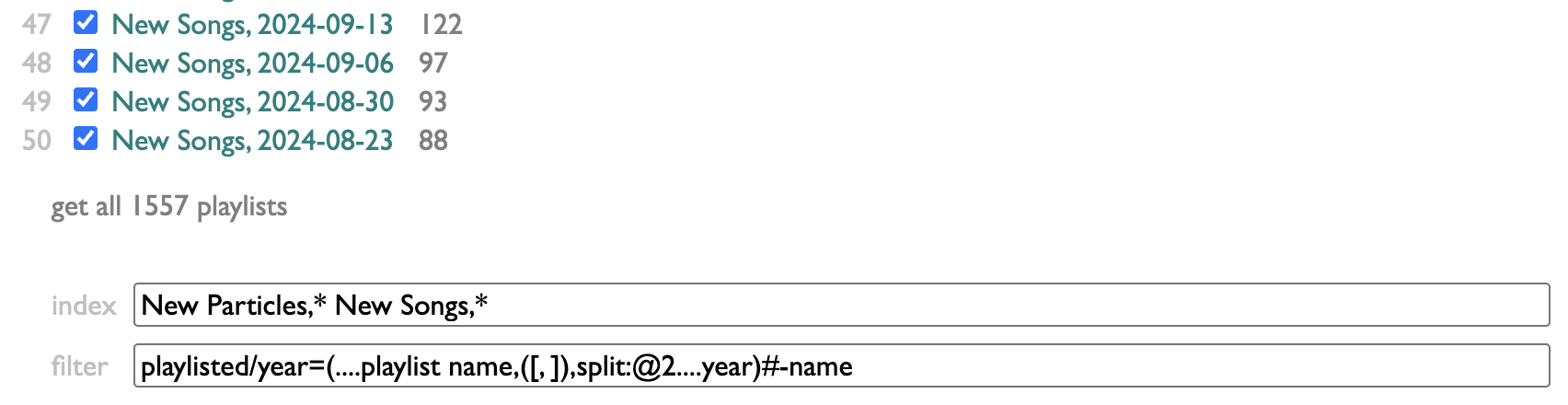

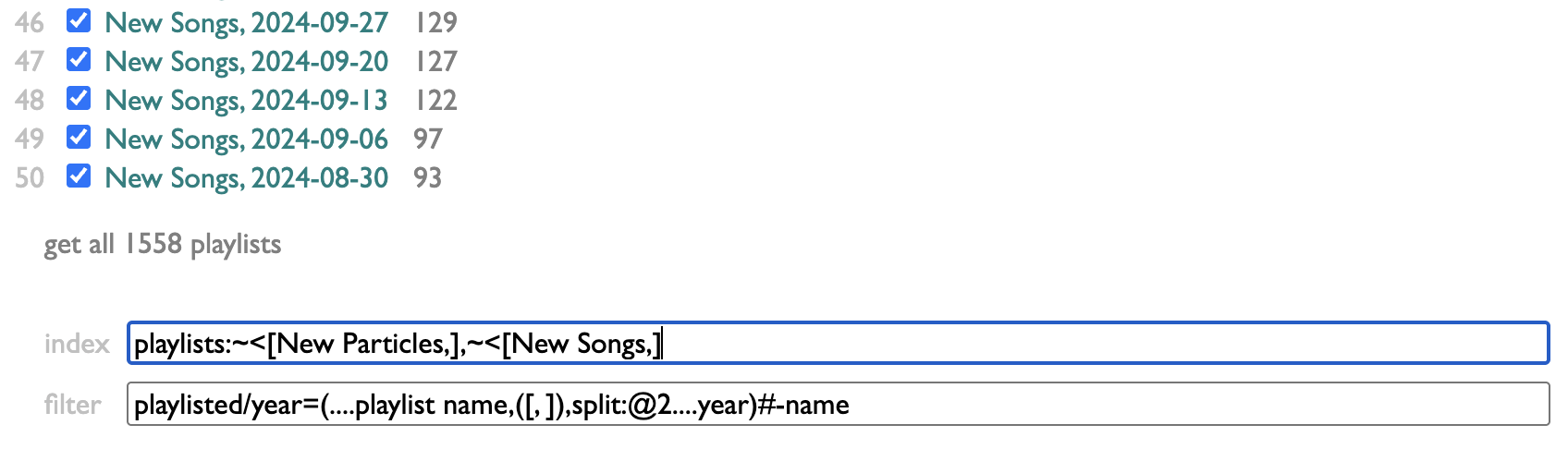

The controls for it are at the bottom of the Playlists page in Curio:

index lets you control which of your playlists are indexed. I make a lot of playlists that are not actually expressions of my own tastes or conduits of my listening, so I've chosen to only index the ones that begin with "New Particles," or "New Songs,". You can put any number of name-prefixes here, ending each one with an asterisk.

filter lets you provide a set of filters in the form of substrings to match against playlist titles. Separate them with commas, and if you start one of the filters with an asterisk, that will give you a magic filter that selects everything, labeled without the asterisk: so "*all" here produces an all-filter labeled "all".

That's kinda flexible, but having to type out the exact filters you want only makes sense if the set is small and doesn't change much, and only doing substring-matching against playlist names is a pretty limited scope.

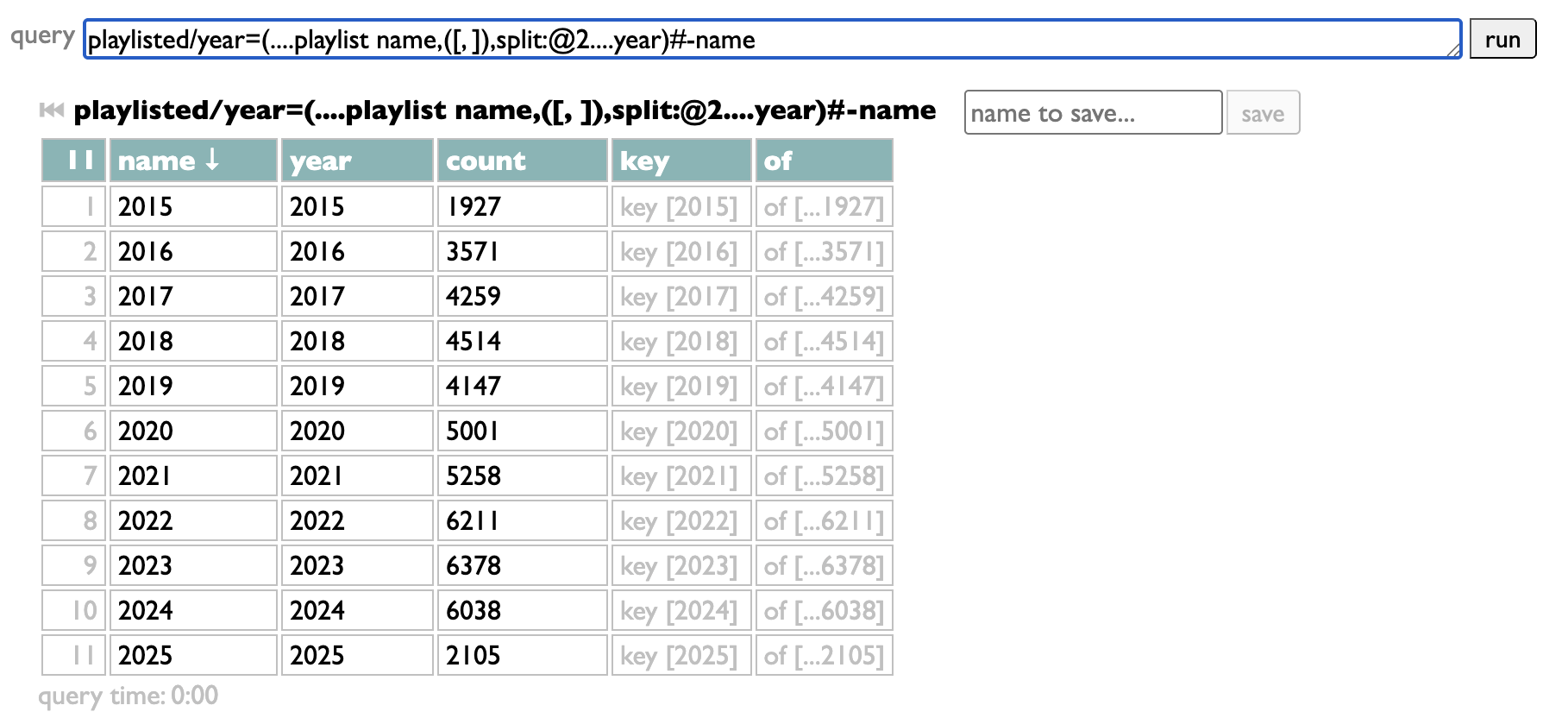

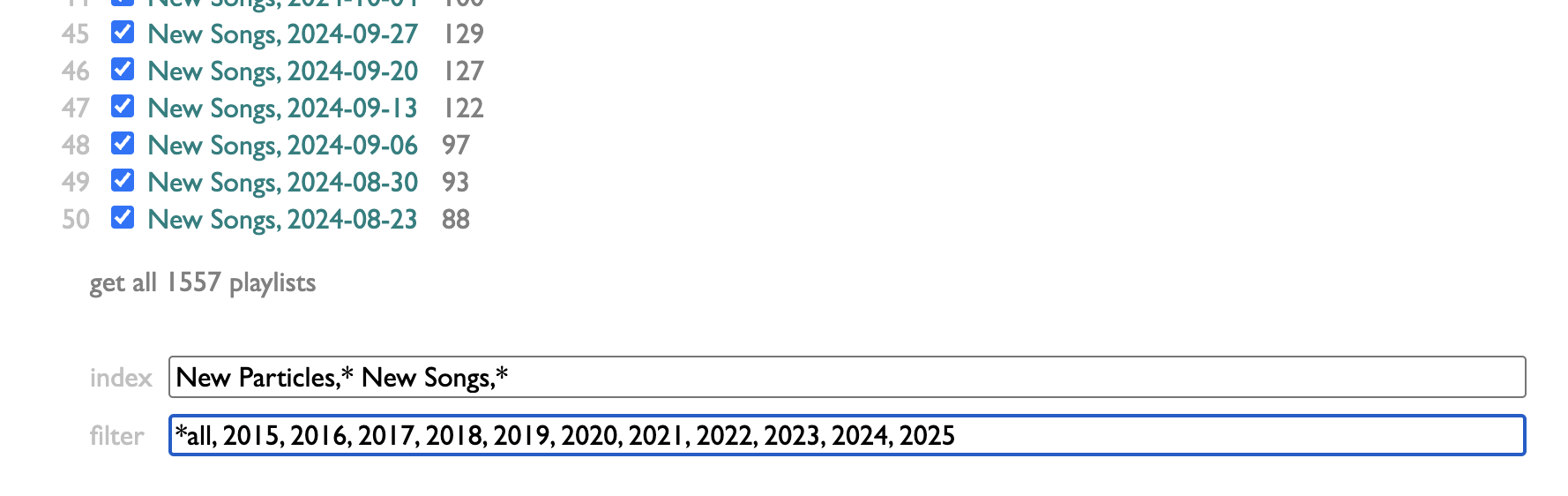

So the other way you can configure filters is by writing a Dactal query. It has to start with playlisted, which gets you the list of all the tracks from all the indexed playlists.

It has to end with groups of those tracks.

The groups are the filter choices. My query takes the playlist name, splits it at the comma to extract the date, pulls the year out of that date, groups by that year, and sorts the resulting year-groups in numeric order. But as long as your query starts with "playlisted" and ends with groups, in between it can do whatever you want. Once you have it working your way, just copy it into the "filter" box:

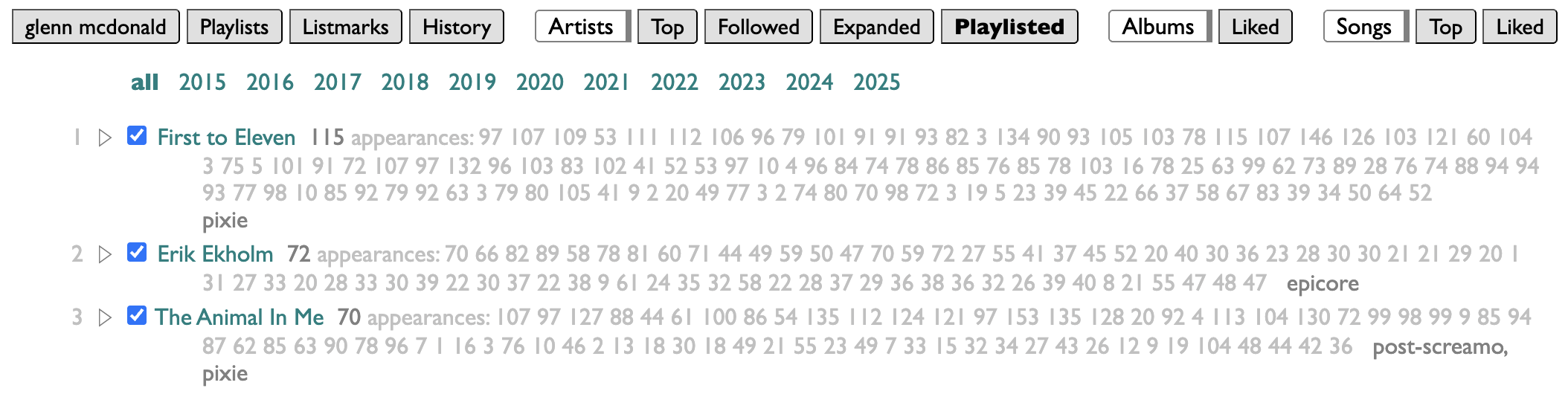

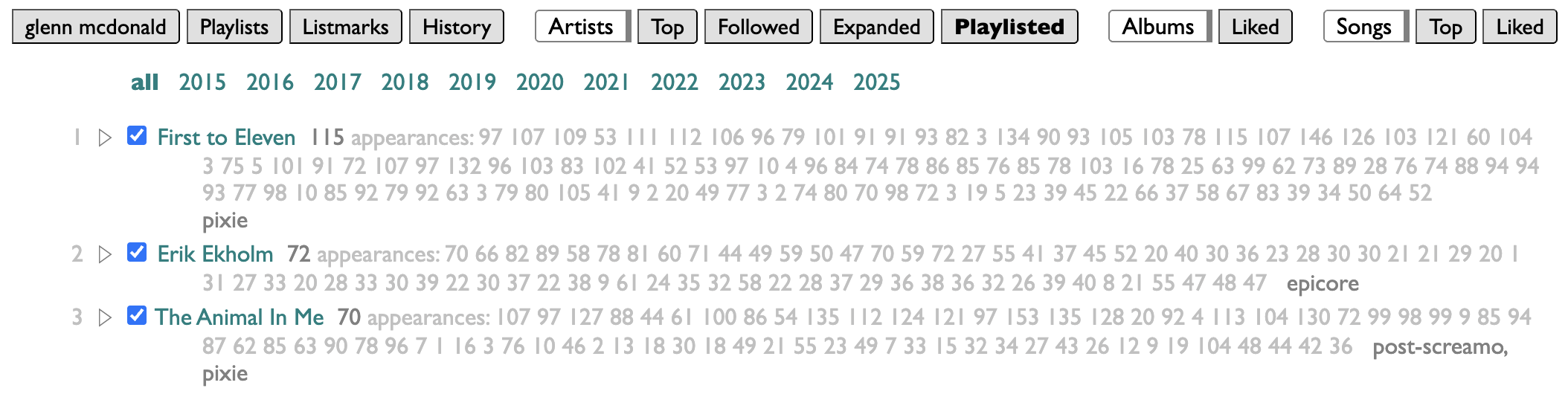

The magic "all" filter is added automatically if you're using a query. I should probably add an option to control that, but I haven't yet. This gets us back to:

...except dynamically, now, so I won't have to remember to add 2026 by hand, it will just appear when needed. Assuming, bravely, that neither AI nor fascists have consumed us before then.

If Curio were a commercial application, surely we would never ship a feature anywhere near this awkward and unguarded. But it isn't, and "we" is me, and I'm trying to imagine what the world could be like if your software invited you to be awkward and unguarded instead of pandered to; curious instead of customers.

PS: Also...

Personally, I organize my listening in weeks, and model those weeks in playlists. Curio has a page for looking at which artists you have put in your playlists, and how often. And because my playlists are dated, it makes sense to me to be able to filter mine by year. But because this may not make the same sense for your playlists, I didn't build a year-filtering feature, I built a filtering feature.

The controls for it are at the bottom of the Playlists page in Curio:

index lets you control which of your playlists are indexed. I make a lot of playlists that are not actually expressions of my own tastes or conduits of my listening, so I've chosen to only index the ones that begin with "New Particles," or "New Songs,". You can put any number of name-prefixes here, ending each one with an asterisk.

filter lets you provide a set of filters in the form of substrings to match against playlist titles. Separate them with commas, and if you start one of the filters with an asterisk, that will give you a magic filter that selects everything, labeled without the asterisk: so "*all" here produces an all-filter labeled "all".

That's kinda flexible, but having to type out the exact filters you want only makes sense if the set is small and doesn't change much, and only doing substring-matching against playlist names is a pretty limited scope.

So the other way you can configure filters is by writing a Dactal query. It has to start with playlisted, which gets you the list of all the tracks from all the indexed playlists.

It has to end with groups of those tracks.

The groups are the filter choices. My query takes the playlist name, splits it at the comma to extract the date, pulls the year out of that date, groups by that year, and sorts the resulting year-groups in numeric order. But as long as your query starts with "playlisted" and ends with groups, in between it can do whatever you want. Once you have it working your way, just copy it into the "filter" box:

The magic "all" filter is added automatically if you're using a query. I should probably add an option to control that, but I haven't yet. This gets us back to:

...except dynamically, now, so I won't have to remember to add 2026 by hand, it will just appear when needed. Assuming, bravely, that neither AI nor fascists have consumed us before then.

If Curio were a commercial application, surely we would never ship a feature anywhere near this awkward and unguarded. But it isn't, and "we" is me, and I'm trying to imagine what the world could be like if your software invited you to be awkward and unguarded instead of pandered to; curious instead of customers.

PS: Also...

¶ Query geekery motivated by music geekery · 27 January 2025 listen/tech

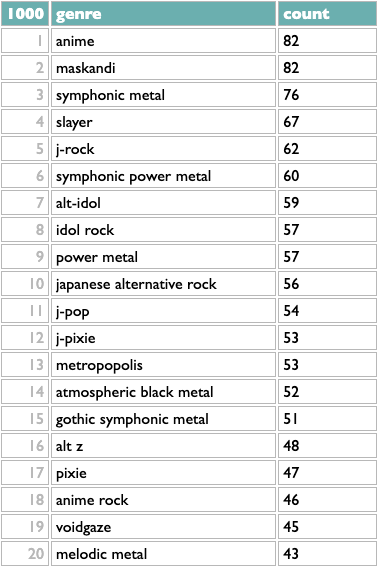

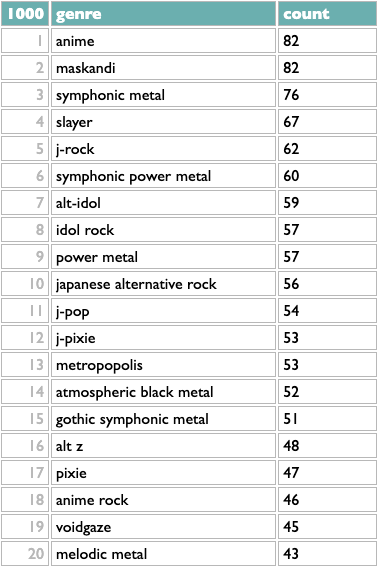

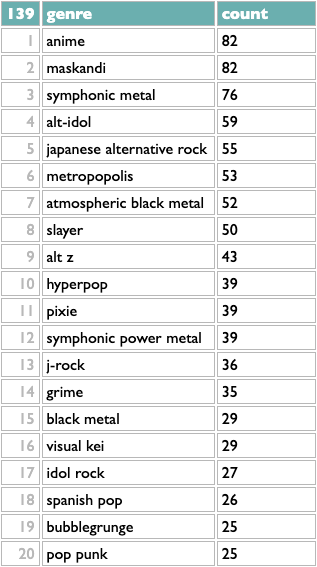

The listening-history tools in Curio include a thing for telling you the top genres from your listening year, because I think that's interesting.

Counting genres with Dactal, the query language in Curio, is easy. Or, at least, counting them in the simplest way is easy:

Take the list of artists (in this case the artists whose new 2024 songs you listened to in 2024), group them by genre, sort the genres by count.

Artists can and often do belong to multiple genres, though, so you might reasonably guess that some these overlap: symphonic metal and symphonic power metal; anime, j-rock, alt-idol, idol rock?

One very simple algorithm for reducing a set of overlapping categories to a smaller representative set is to take the genre with the most artists, then remove all the artists with that genre (whether they have other genres or not), then repeat. Dactal has a repeat operator for doing this kind of thing. We need a few other query features to make the query we need, but it's still fairly simple:

? is the Dactal start operator, which is implied at the beginning of a query and thus often doesn't actually appear at all, but here we use it to effectively interleave queries that keep track of the genres we've found and the artists we have left. We begin with all the artists and no genres, and then the indented subquery does two things:

- remove the artists from the last genre, using the set disjunction filter :-~~ (which does nothing the first time, because there are no genres yet)

- find the top genre for the artists we have left and add it to the existing list of topgenres

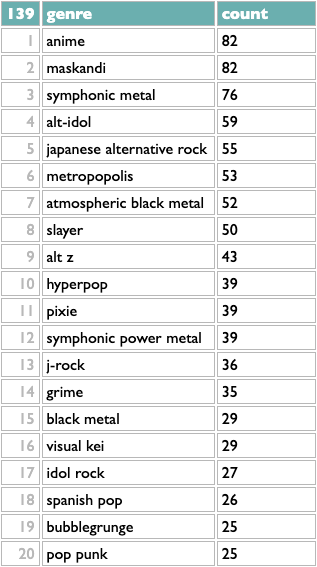

The ! repeat operator at the end of the subquery tells it to repeat the previous operation until it produces the same result twice (meaning there's nothing left to add), which happens for me after 139 iterations:

This is a little better. Flipping back and forth, I see that j-rock was 5th in the raw version, with 62 artists, but in the iterative version it drops to 13th, because only 36 of those 62 artists aren't part of any higher-ranked genres. Similarly, symphonic power metal drops from 6th to 12th. Japanese alternative rock moves up, because only 1 of those 56 artists was being double-counted before.

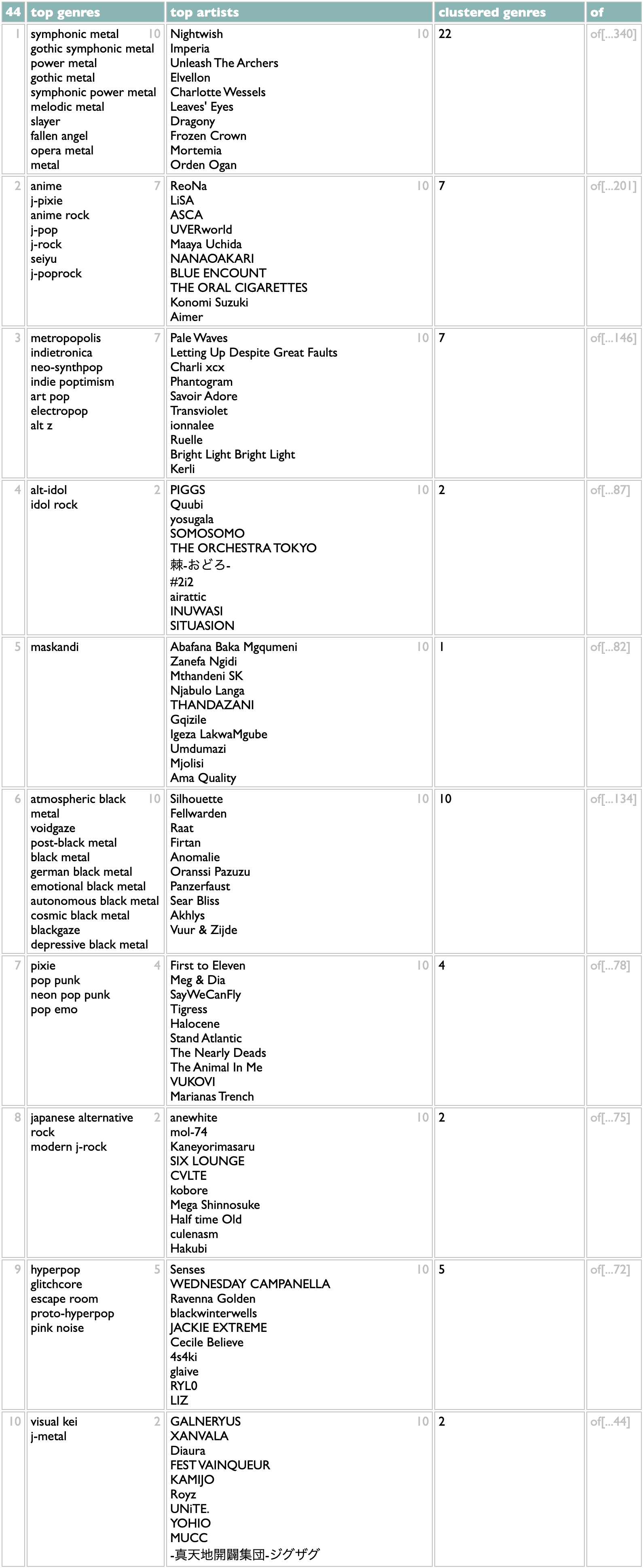

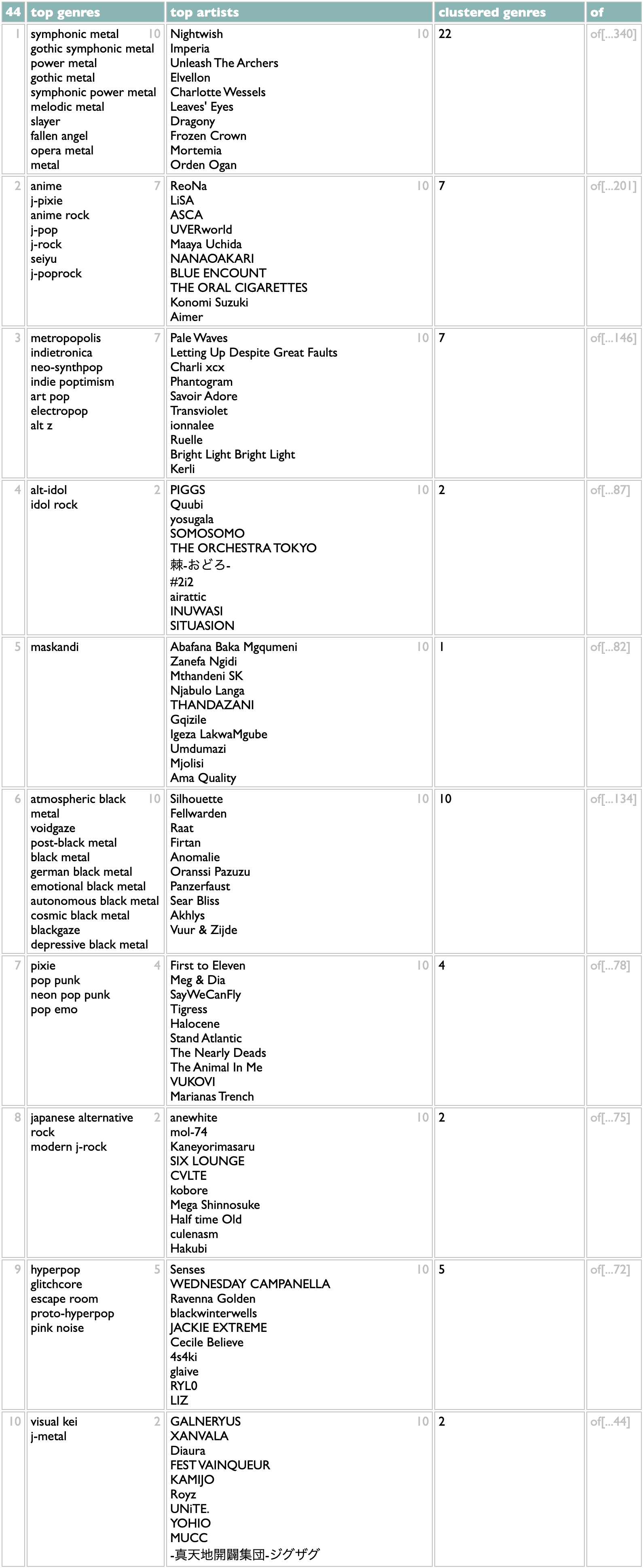

Really, though, this list of 139 "representative" genres still overstates the granularity into which my listening is emotionally organized. If you do not tend to use the words "granularity" and "emotionally" in the same sentences in your internal monologue, then you should probably cut your losses and tune out now. In order to cluster genres instead of just subsetting them, we need almost every major feature of Dactal:

I'm not going to claim this is "easy", but I've written variations on this algorithm in Ruby, Python, SQL and Javascript over the years, and I can tell you that all of those versions were much longer and involved way more punctuation than this, in addition to a lot more words that are about computers instead of about music.

The first two steps of the clustering are about the same as in the simpler version: eliminate any artists we've already used, and then find the top genre. Here we're scoring genres by summing up the square roots of artist points, instead of just counting artists, to measure a combination of listening breadth and listening depth, but that's added complexity in the question, not just the answer.

The clustering part is that once we have a top genre, we take all its artists and count their other genres, and then compare the overlap sizes with those genres' total artist counts (using lookups in the genre index created in the second line of the query). Other genres that overlap non-trivially with the first genre also get added to the cluster. Then the whole thing repeats. So instead of building a flat list of genres, this version builds a list of nested genre lists.

This is, for me, a lot closer to correct than the flat list, and certainly more interesting. It doesn't distribute my Japanese tastes exactly right (I don't care about anime, per se, so I usually put ReoNa and LiSA with the alt-idol groups for sonic reasons), but these first 10 statistical clusters are all aspects of my taste that I would list individually if you inadvisedly gave me an excuse, and of the 44 ways it breaks down my 2024, the only ones that get me thinking about override mechanics are towards the bottom where the genre data doesn't know that I tend to put the Spanish metal bands and the medieval rock nerds in with the other melodic metal styles.

If you want to try this on your own listening, there are now both "genres" and "genre clusters" views on the History page in Curio. But as with all of those, there is also a "see the query for this" at the bottom of the results, so if you want to experiment with variations, you can.

Although by you, as usual, I probably mean me. But by me I mean all of us.

Counting genres with Dactal, the query language in Curio, is easy. Or, at least, counting them in the simplest way is easy:

2024 artists scored/genre=(.artist.artist genres.genres)#count

Take the list of artists (in this case the artists whose new 2024 songs you listened to in 2024), group them by genre, sort the genres by count.

Artists can and often do belong to multiple genres, though, so you might reasonably guess that some these overlap: symphonic metal and symphonic power metal; anime, j-rock, alt-idol, idol rock?

One very simple algorithm for reducing a set of overlapping categories to a smaller representative set is to take the genre with the most artists, then remove all the artists with that genre (whether they have other genres or not), then repeat. Dactal has a repeat operator for doing this kind of thing. We need a few other query features to make the query we need, but it's still fairly simple:

artistsx=(2024 artists scored|genre=(.id.artist genres.genres))

?topgenres=()

?(

?artistsx=(artistsx:-~~(topgenres:@@1.of))

?topgenres=(topgenres,(artistsx/genre:count>=5#count:@1))

)!

?topgenres=()

?(

?artistsx=(artistsx:-~~(topgenres:@@1.of))

?topgenres=(topgenres,(artistsx/genre:count>=5#count:@1))

)!

? is the Dactal start operator, which is implied at the beginning of a query and thus often doesn't actually appear at all, but here we use it to effectively interleave queries that keep track of the genres we've found and the artists we have left. We begin with all the artists and no genres, and then the indented subquery does two things:

- remove the artists from the last genre, using the set disjunction filter :-~~ (which does nothing the first time, because there are no genres yet)

- find the top genre for the artists we have left and add it to the existing list of topgenres

The ! repeat operator at the end of the subquery tells it to repeat the previous operation until it produces the same result twice (meaning there's nothing left to add), which happens for me after 139 iterations:

This is a little better. Flipping back and forth, I see that j-rock was 5th in the raw version, with 62 artists, but in the iterative version it drops to 13th, because only 36 of those 62 artists aren't part of any higher-ranked genres. Similarly, symphonic power metal drops from 6th to 12th. Japanese alternative rock moves up, because only 1 of those 56 artists was being double-counted before.

Really, though, this list of 139 "representative" genres still overstates the granularity into which my listening is emotionally organized. If you do not tend to use the words "granularity" and "emotionally" in the same sentences in your internal monologue, then you should probably cut your losses and tune out now. In order to cluster genres instead of just subsetting them, we need almost every major feature of Dactal:

?artistsx=(2024 artists scored|genre=(.id.artist genres.genres),weight=(....artistpoints,sqrt))

?genre index=(artistsx/genre,of=artists:count>=5)

?clusters=()

?(

?artistsx=(artistsx:-~~(clusters:@@1.of))

?nextgenre=(artistsx/genre,of=artists:count>=10#(.artists....weight,total),count:@1)

?nextcluster=(

nextgenre.artists/genre,of=artists:count>=5

||total=(.genre.genre index.count),overlap=[=count/total]

:(.total) :overlap>=[.1] #(.artists....weight,total),count

...top genres=(.genre:@<=10),

top artists=(.artists:@<=10.name),

clustered genres=(.genre....count),

of=(.genre.genre index.artists)

:(.top genres)

)

?clusters=(clusters,nextcluster)

)!

?genre index=(artistsx/genre,of=artists:count>=5)

?clusters=()

?(

?artistsx=(artistsx:-~~(clusters:@@1.of))

?nextgenre=(artistsx/genre,of=artists:count>=10#(.artists....weight,total),count:@1)

?nextcluster=(

nextgenre.artists/genre,of=artists:count>=5

||total=(.genre.genre index.count),overlap=[=count/total]

:(.total) :overlap>=[.1] #(.artists....weight,total),count

...top genres=(.genre:@<=10),

top artists=(.artists:@<=10.name),

clustered genres=(.genre....count),

of=(.genre.genre index.artists)

:(.top genres)

)

?clusters=(clusters,nextcluster)

)!

I'm not going to claim this is "easy", but I've written variations on this algorithm in Ruby, Python, SQL and Javascript over the years, and I can tell you that all of those versions were much longer and involved way more punctuation than this, in addition to a lot more words that are about computers instead of about music.

The first two steps of the clustering are about the same as in the simpler version: eliminate any artists we've already used, and then find the top genre. Here we're scoring genres by summing up the square roots of artist points, instead of just counting artists, to measure a combination of listening breadth and listening depth, but that's added complexity in the question, not just the answer.

The clustering part is that once we have a top genre, we take all its artists and count their other genres, and then compare the overlap sizes with those genres' total artist counts (using lookups in the genre index created in the second line of the query). Other genres that overlap non-trivially with the first genre also get added to the cluster. Then the whole thing repeats. So instead of building a flat list of genres, this version builds a list of nested genre lists.

This is, for me, a lot closer to correct than the flat list, and certainly more interesting. It doesn't distribute my Japanese tastes exactly right (I don't care about anime, per se, so I usually put ReoNa and LiSA with the alt-idol groups for sonic reasons), but these first 10 statistical clusters are all aspects of my taste that I would list individually if you inadvisedly gave me an excuse, and of the 44 ways it breaks down my 2024, the only ones that get me thinking about override mechanics are towards the bottom where the genre data doesn't know that I tend to put the Spanish metal bands and the medieval rock nerds in with the other melodic metal styles.

If you want to try this on your own listening, there are now both "genres" and "genre clusters" views on the History page in Curio. But as with all of those, there is also a "see the query for this" at the bottom of the results, so if you want to experiment with variations, you can.

Although by you, as usual, I probably mean me. But by me I mean all of us.

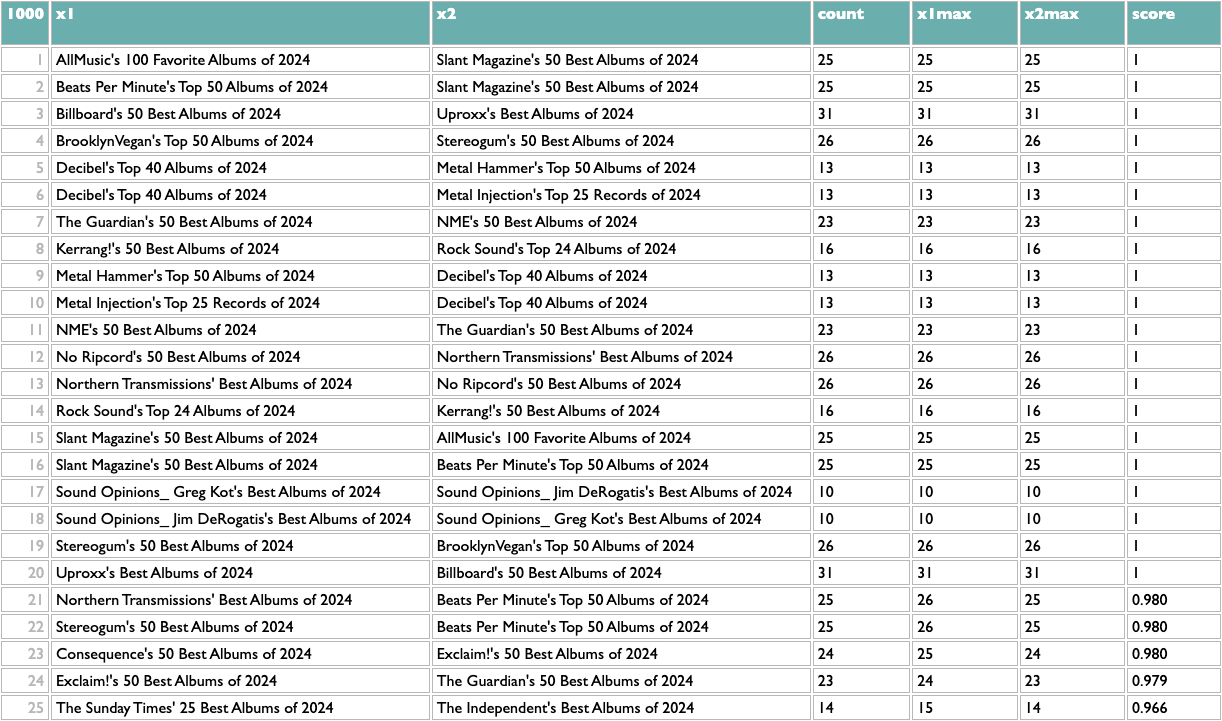

¶ What we know · 14 January 2025 listen/tech

The thing I worked on the longest, in my Echo Nest / Spotify time, was calculating artist similarity. In the Echo Nest days, when we didn't have direct listening data, we derived scores for pairs of artists based on patterns of shared descriptive words found in web pages about each of them. Or, more accurately, web pages maybe about them, because figuring out whether any given blob of text that contains a given string of letters is about a band whose name is that same string of letters, at all never mind in a descriptively useful sense, is hard.

Once we got swallowed by Spotify, of course, we had all the listening-data plankton we could krill. The goal of "collaborative filtering", taken most lowercasely, is to extract collective knowledge from collected data. The Spotify feature this work powered was called (eventually) Fans Also Like, and one of my greatest organizational triumphs at Spotify was that after many years of technical work and political lobbying, I succeeded in making this feature live up to its name. For about a year and a half, starting around April 2023, the Spotify artist page Fans Also Like lists were really an algebraic formulation of getting each artist's fans, not just listeners, and finding out what other artists they disproportionately also liked. And nothing else. You only saw the first 20 results for each artist, but the underlying dataset behind this went deeper, and I think was a genuinely unprecedented collective cultural achievement of the Spotify audience.

Most of the complexity of doing this well, if by "well" you mean reflecting actual patterns of human interest as opposed to round-off error in vector embeddings or clandestine margin-chiseling, which you should, was actually in the quantification of "fan". I would not be able to explain all the details of that process from memory, even if I were allowed to, but the core idea is that the more you raise the threshold of fandom, the better similarity signal you get from the listening patterns of those fans, but the fewer artists are included, so if you want both precision and recall, you have to get creative.

And of course you have to get data, to begin with. We cannot recreate the lost Fans Also Like network from outside of Spotify, because we cannot get their dataset of fan/artist pairs. Or, really, our dataset, because it's our listening.

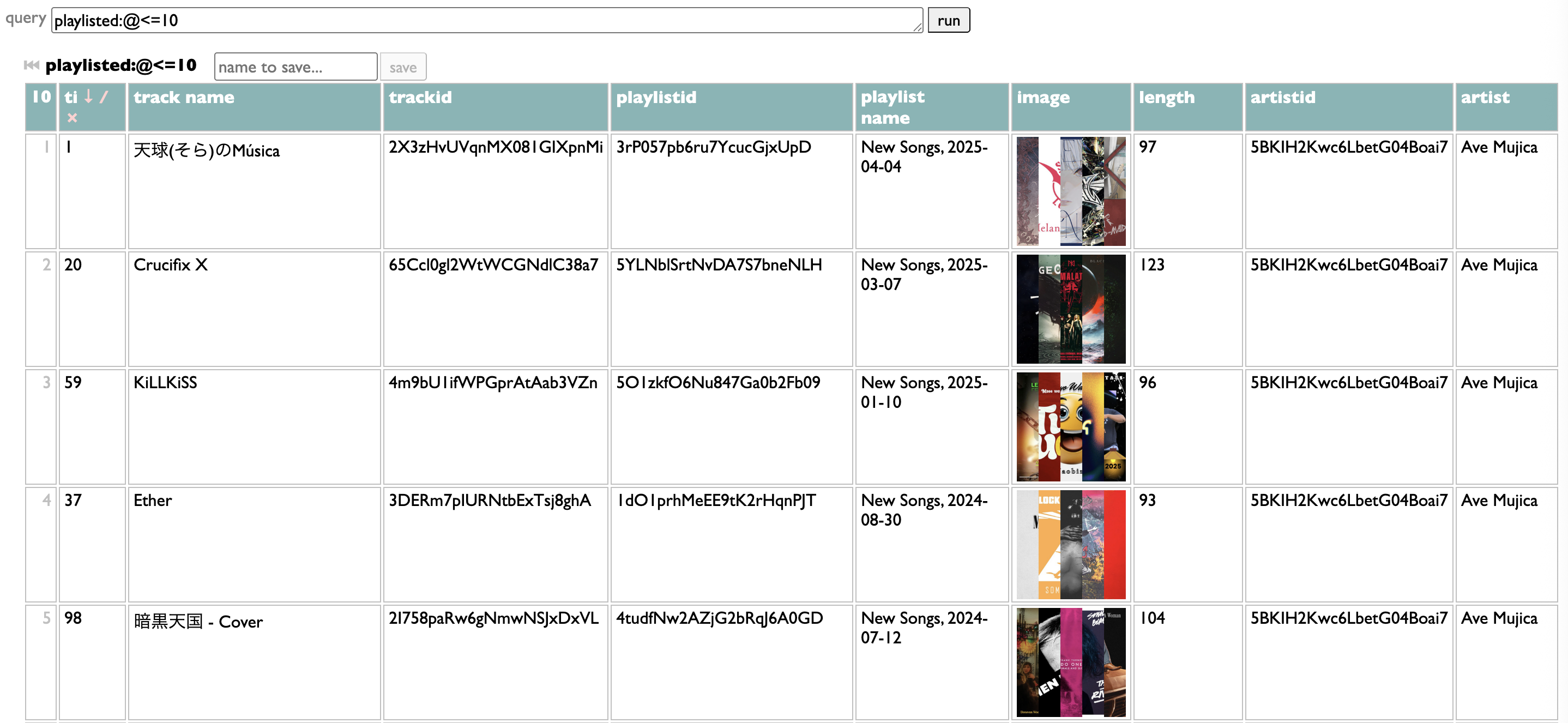

If you happen to have pairs of any kind of data, though, doing simple math to extract similarity of one half of those pairs based on the co-reference patterns of the other half is easy. In fact, if you have that pair data in JSON, you can load it into the spec/doc/test/playground page for Dactal and do it right now.

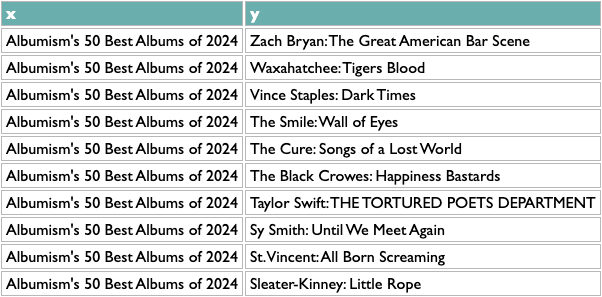

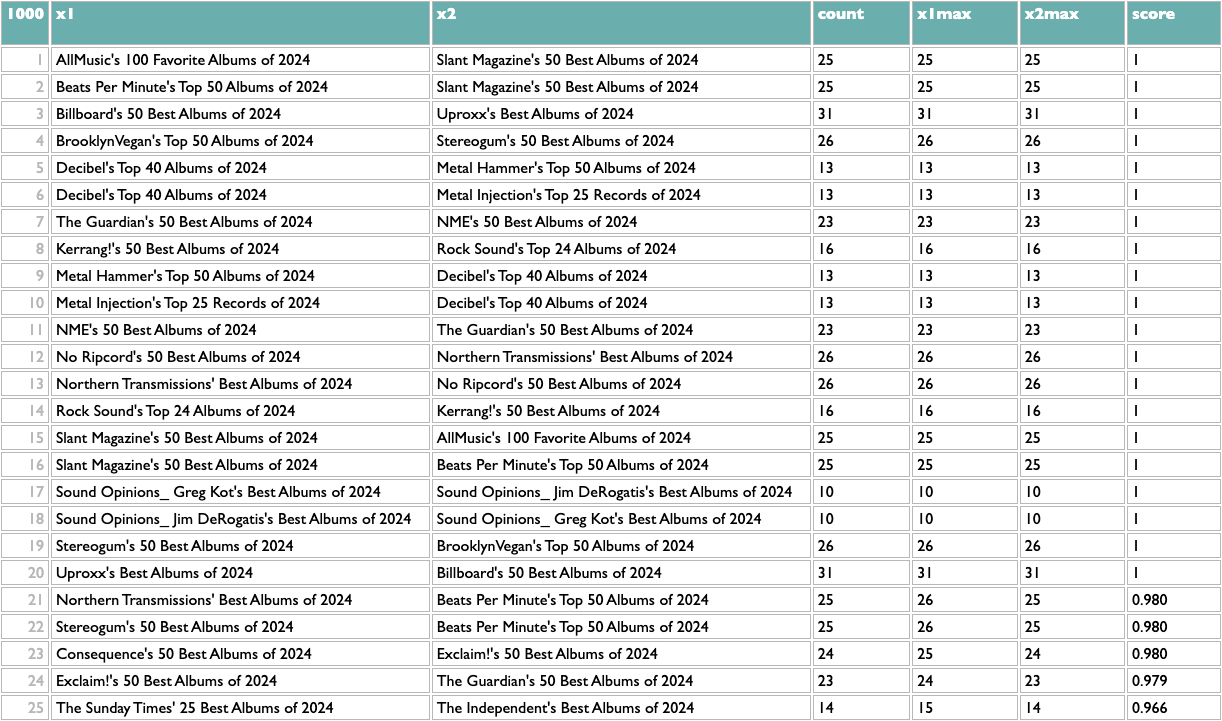

For example, over at AlbumOfTheYear.org they aggregate album-of-the-year lists from many other publications and produce a scored meta-ranking of the year's albums. But this dataset of publication/album pairs also encodes patterns of implicit knowledge about album similarity based on the tendencies of publications to list albums together, and about publication similarity based on the tendencies of albums to appeal to publications together.

Here's how to extract it using Dactal:

The first orange line is specific to this data, my extraction from the AOTY lists, but all it needs to produce is a two-column list with x and y. Like this:

Once you have any x/y list like this, the rest of the query works the same. The scoring logic here (which isn't what I used at Spotify, but you probably aren't dealing with 600 million people listening to 10 million artists) counts the overlap between any pair of x based on y, and then scales that by the maximum overlaps of both parts of the pair. So a score of 1 means that both things in that pair are each other's closest match. The calculation is asymmetric because one part of a pair may be the other's closest match but not vice versa. If you read about music online you may know that, e.g., Decibel and Metal Hammer are both metal-specific, The Guardian and NME are both British, and BrooklynVegan and Stereogum are both read by the kind of people who read BrooklynVegan and Stereogum, so the top of those results passes a basic sanity check.

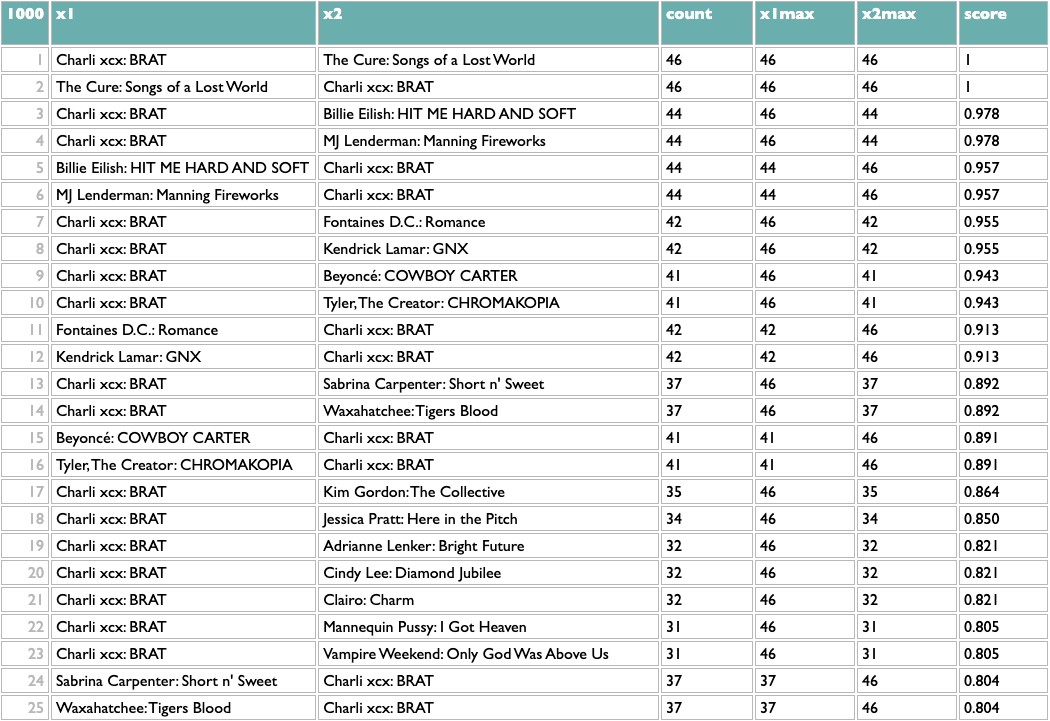

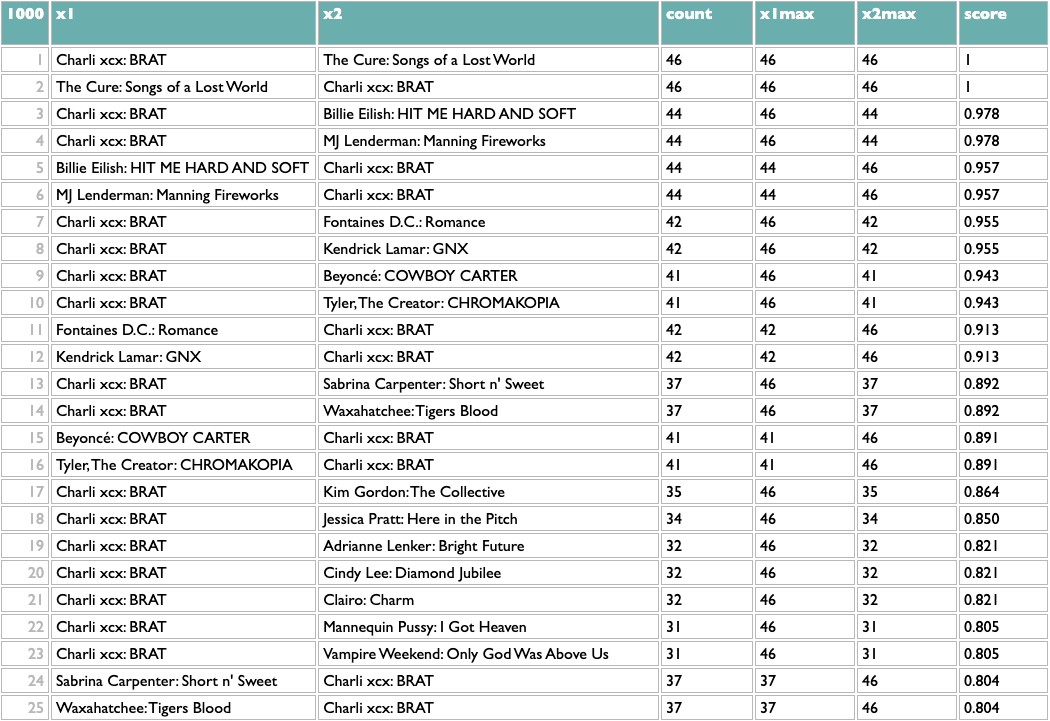

And because everything but the first line is independent of what x and y are, that means we can flip x and y (just those two letters!) and get album similarity:

This passes a sanity check – everybody who writes about music likes Charli – but not an interestingness check, so we might opt to filter out BRAT just to see what else we can learn:

Not bad! The two Future/Metro Boomin albums are most similar to each other, which is the good kind of confidence-boosting boring answer, but a bunch of the other pairs are plausible yet non-obvious: two indie rock records, two UK indie guitar records, two indie rappers, two metal-adjacent records.

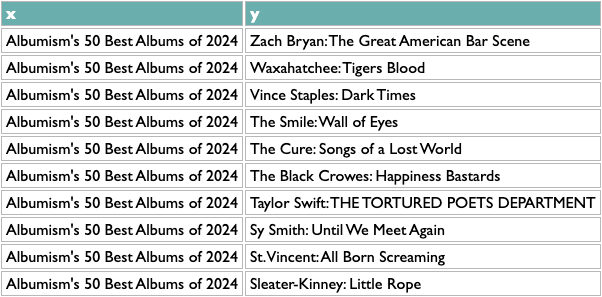

These scores are normalized locally, not globally, so the real way to use them is to reorganize this by album. Which is also easy:

That's interesting to me. What's interesting to you?

[PS: Oh, here, I put this dataset up in raw interactive form, so you can play with it yourself if you want.]